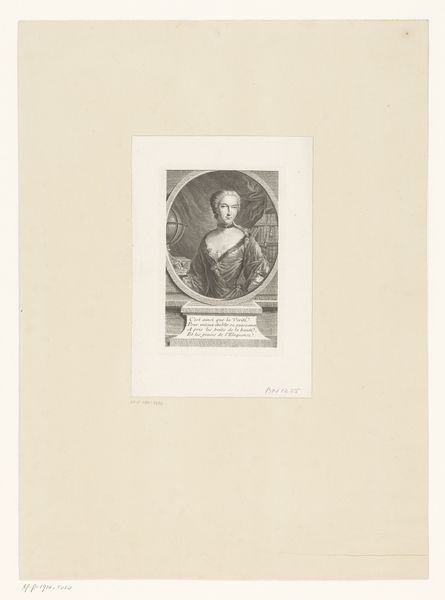

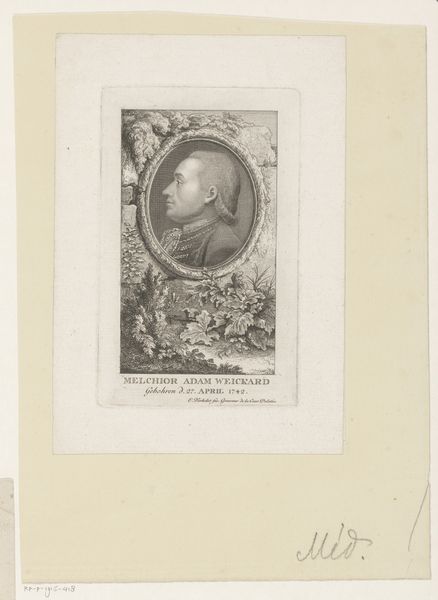

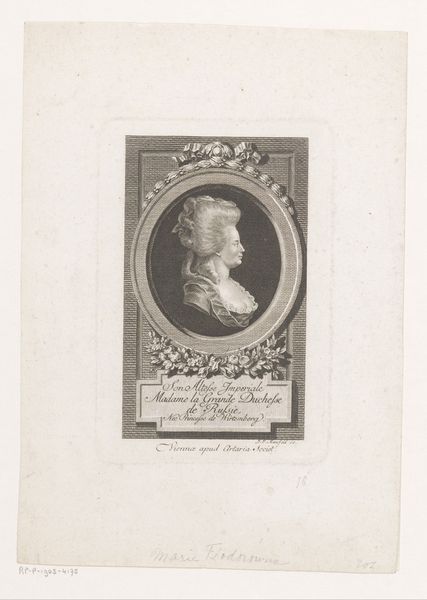

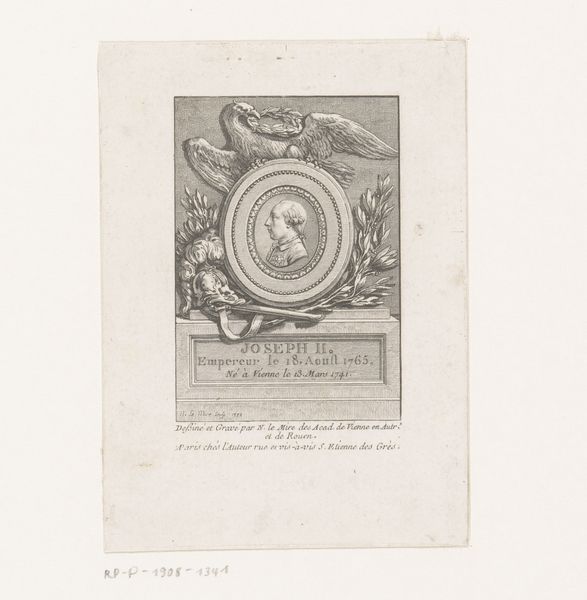

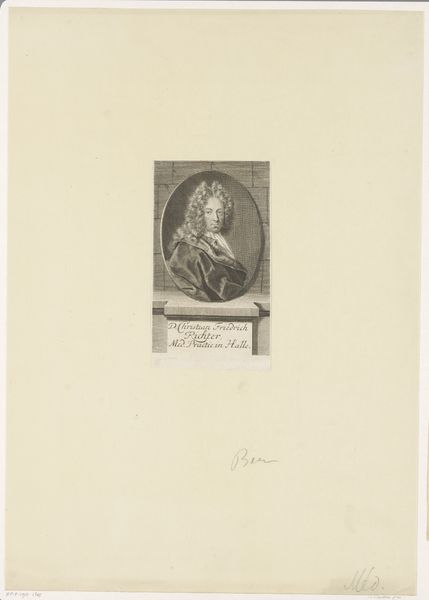

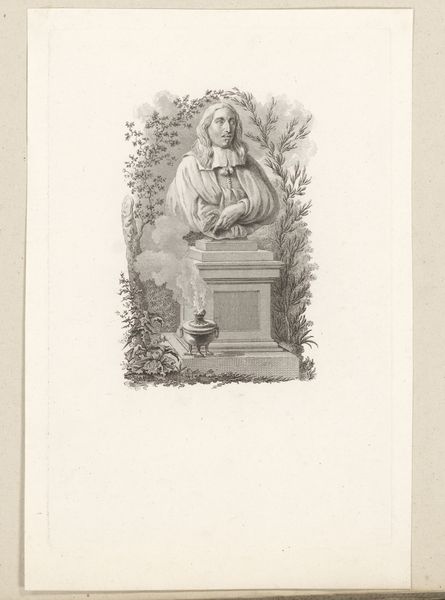

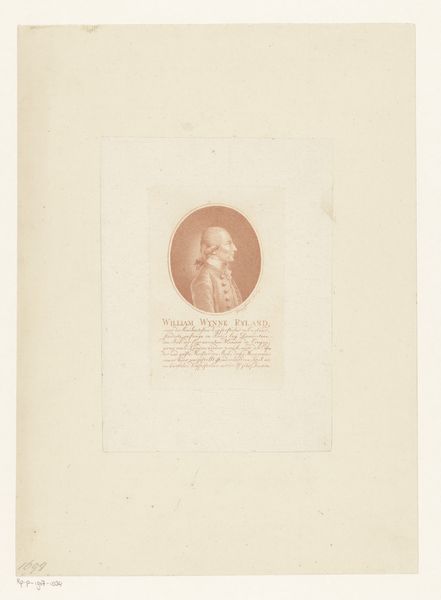

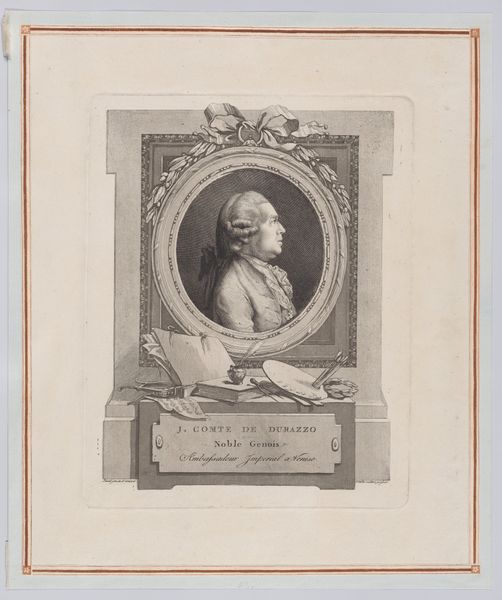

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 219 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Jean Daullé’s "Portret van Maria Theresia van Oostenrijk," created between 1743 and 1763. It's an engraving. The detail is astonishing; you can almost feel the texture of her gown. How do you approach a work like this? Curator: For me, it begins with understanding the material conditions of its production. Engraving involves a very particular kind of labor, painstaking and precise. Think about the engraver, Daullé, meticulously working the metal plate, the pressures he had to apply and the tools employed to achieve the lines and tonality we see. What social status did an engraver such as Daullé hold and for whom was this produced? Editor: So you see the craft itself as integral to understanding the portrait’s meaning? Curator: Absolutely. This wasn’t a unique object like a painting; engravings were produced in multiples. It’s a reproduction meant for wider consumption. Consider how that accessibility challenges notions of high art versus craft. It turns art into commodity but makes accessible likeness of power through mechanical processes, enabling wider distribution and visibility. What was the marketplace like for prints during this period, and who was buying them? Was Daulle working for a royal court or some publisher? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn't considered how the printmaking process itself democratized the image of Maria Theresa, allowing more people access to her likeness. Curator: Precisely! It changes how we view the subject herself. The context of the art is within the economy, production and society of its making, not just within what is visible within the pictorial elements of the print itself. Editor: This gives me so much to think about when looking at art. It opens the piece up. Thanks! Curator: Glad to share; materiality offers such a compelling lens.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.