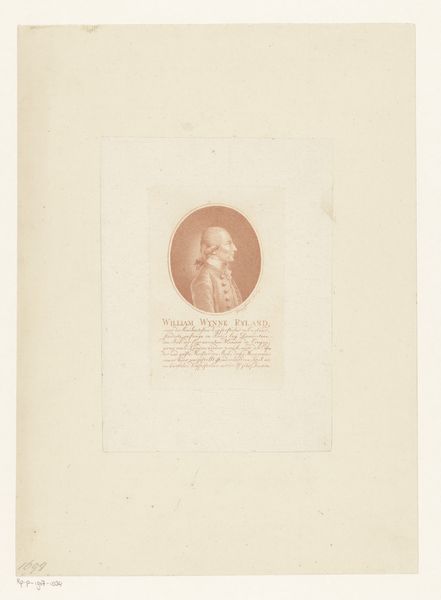

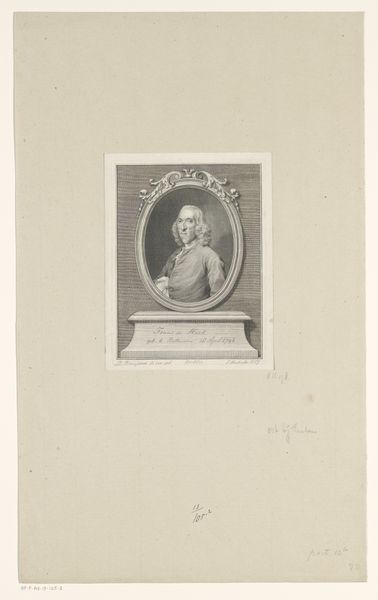

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 141 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At the Rijksmuseum we find an engraving from between 1790 and 1836 titled "Portret van Johann Friedrich Weißenborn." Editor: There’s an austerity to this portrait, wouldn’t you agree? Almost severe, yet composed and carefully rendered. Curator: Yes, and when we consider the production of engravings during that period, we must recognize that their widespread distribution played a crucial role in shaping visual culture. The act of translating an image into an engraving meant the work could be reproduced cheaply and disseminated widely. This particular portrait captures Johann Friedrich Weißenborn, who was a Professor of Medicine in Erfurt. Editor: Considering Erfurt's history, this portrait acquires another layer. We are talking about a prominent scholar in a city that saw deep divisions during the Reformation, followed by waves of religious and social upheaval. As such, it inevitably evokes questions around power, status and intellect within its historical context. Curator: Absolutely, and to your point on power structures: portraits, particularly engravings, served not only as likenesses but also as powerful signifiers of social standing. An academic, captured within a neoclassical oval, all neatly done as reproduction accessible across social lines is quite striking. Editor: Though the neoclassical frame attempts order and hierarchy, I feel it betrays an emergent tension, of a time where rigid structures begin to give way and societal strata becomes more malleable. Do you perceive something in the face itself, beyond what a mere social depiction can encompass? The expression suggests an era marked by change, not of stasis. Curator: Certainly, engraving techniques could reproduce subtle gradations, almost to photorealism and academic-style works intended to serve a larger social and didactic role. These printed images become primary carriers of ideology and ideals and shaped the viewer's experience far outside art gallery settings. Editor: Thinking of this engraving as a manufactured artifact, reproducible on demand to those eager for knowledge or aspiration, challenges traditional, romanticized art, wouldn't you say? Perhaps seeing Weißenborn and figures such as himself as an instrumental figure beyond Erfurt and his academic work gives the work continued relevance and immediacy to our social awareness. Curator: Precisely. This engraving isn't just an isolated artwork but a node within extensive networks of material production and dissemination, impacting how identities were crafted and consumed across Europe. Editor: I concur. Approaching it with that in mind reframes our entire discussion around materiality and ideology. It's a useful mental approach!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.