Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

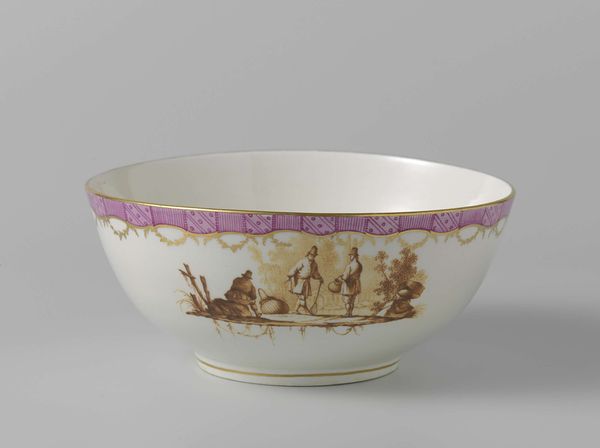

Curator: This charming ceramic punch bowl, estimated to have been made sometime between 1750 and 1775, comes to us from an anonymous artist. What’s your first reaction to it? Editor: It feels so…immediate. The cobalt blue illustrations on the creamy stoneware surface vividly depict scenes of rowdy revelry, all swirling around this central vessel, almost as if it's capturing a stolen moment in time. Curator: Indeed. The fact that such intimate genre scenes and even erotic art motifs are painted on a utilitarian object like a punch bowl offers fascinating insights into 18th-century European society. Think of the artisanal skills required to craft the ceramic itself, and then imagine a hand carefully painting such details. Editor: Right. Who had access to this kind of object, and who was denied it? Given the depiction of people behaving rather badly, one has to consider questions of class and access. This isn't just decorative art; it's a potential reflection of societal anxieties or norms made manifest in an everyday object. The Dutch East India Company was flourishing then; were these drunken parties perhaps indirectly financed by the proceeds of colonialism? Curator: It's tempting to link the consumption depicted on the bowl directly to a critique of social inequity, and I wouldn't discount the role that porcelain played in colonial commerce. At the same time, focusing on process, on materials, tells another story. The popularity of Delftware, as it was known, represented a particular material response: Dutch artisans immitating then-rare, precious, and imported Asian porcelain in local clay. This points to a society concerned not merely with aesthetics, but increasingly with industrial processes. Editor: I see your point about materiality shaping production, and vice-versa, but I am concerned that this viewpoint risks sidelining crucial aspects related to identity, power, and cultural exchange. While admiring craft, we should acknowledge how labor, erotic imagery, and power dynamics intertwined to produce pieces like this. Curator: I suppose both viewpoints have some degree of merit. Perhaps a bit of both—the material realities of the means of production, but also critical analyses of colonial contexts are crucial to appreciating its place in art history. Editor: Absolutely, that convergence is vital to fully grasp its lasting relevance today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.