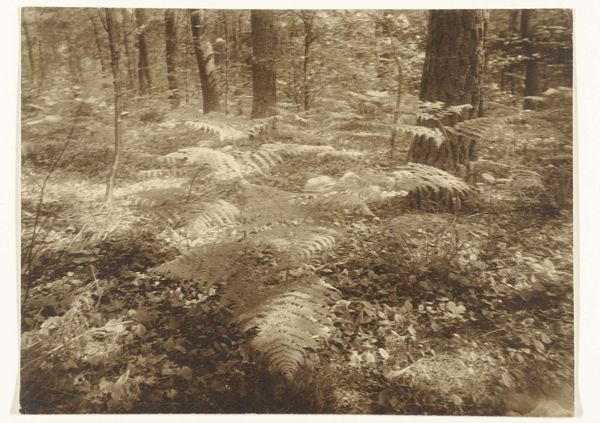

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

#

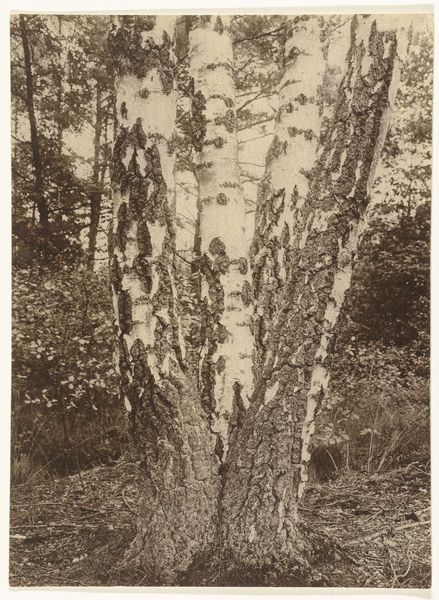

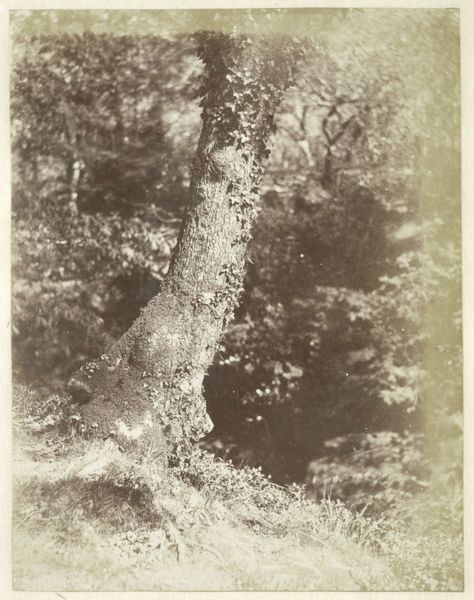

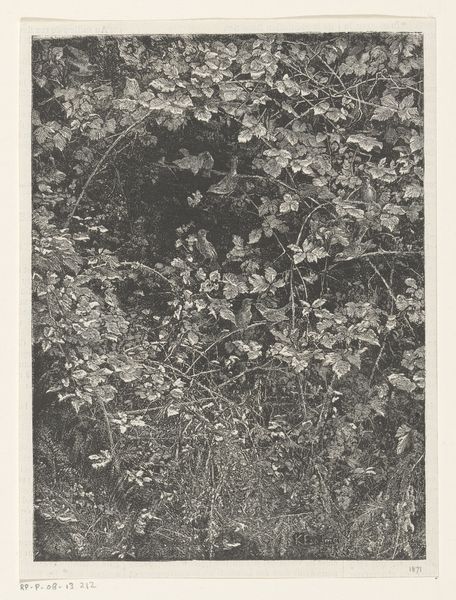

natural shape and form

#

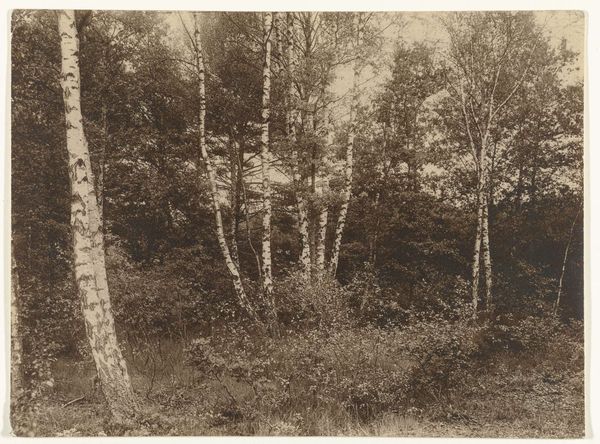

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

united-states

#

realism

Dimensions: 9 1/2 x 7 5/16 in. (24.13 x 18.57 cm) (image, sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

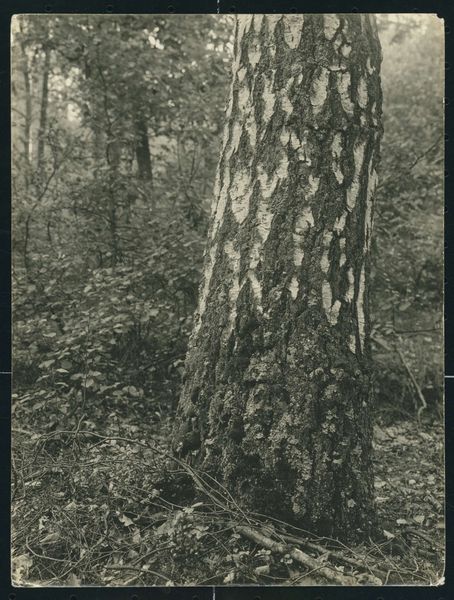

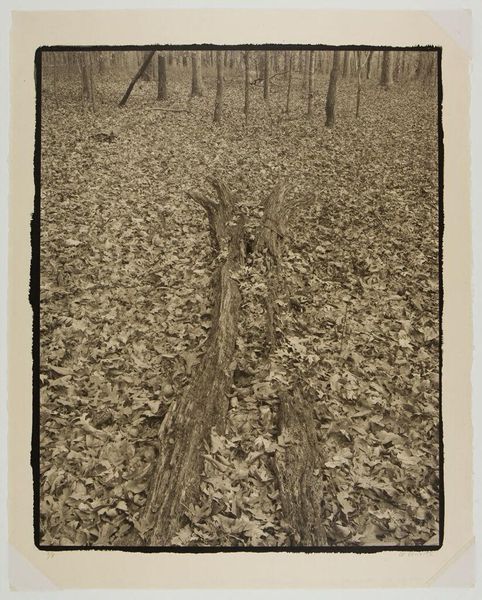

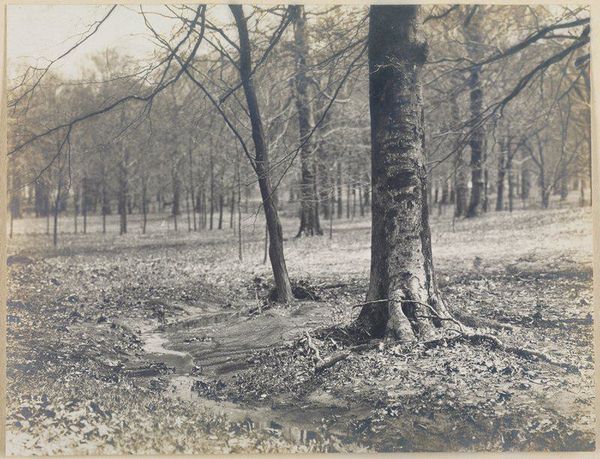

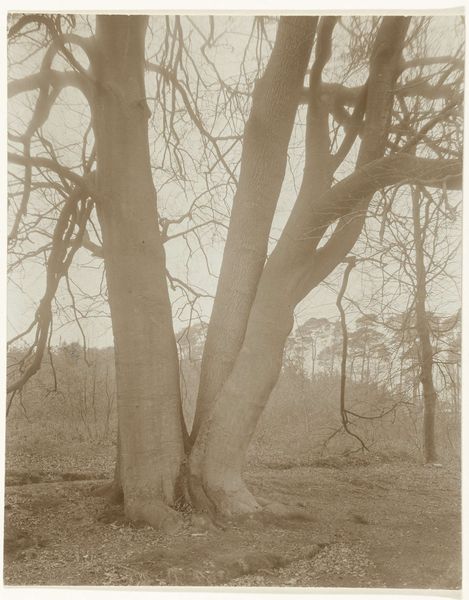

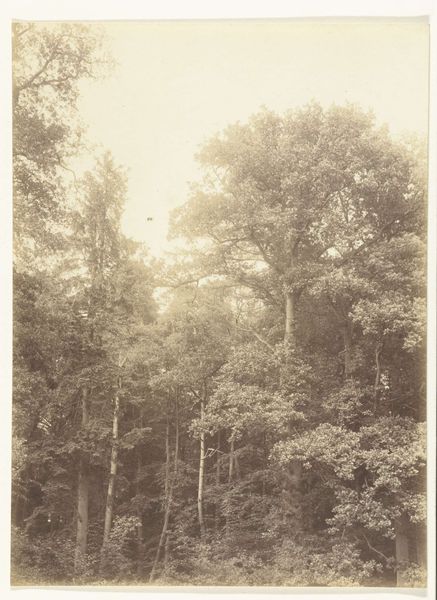

Curator: Looking at Edwin Hale Lincoln’s "Orchis spectabilis- Snowy Orchis" from 1931, a gelatin silver print currently residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I'm struck by how it positions a small bloom within a vast, perhaps even overwhelming, landscape. Editor: It's immediately striking how tactile it feels for a photograph. The rough texture of the tree bark, the intricate details of the fallen leaves, even the delicate petals of the orchis, it all feels rendered with such careful consideration. It draws you in. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the historical context: botanical photography at this time was often tied to scientific documentation. But Lincoln's framing shifts the focus, creating a dialogue about humanity's place within, and relationship to, the natural world. He elevates the act of witnessing the natural world, giving this humble flower agency. Editor: Yes, but think also about the materials. Gelatin silver prints, which were widespread at the time, democratized image production in a way. They made photographic reproducibility more accessible to amateurs. Was this part of Lincoln's project, too: making high-minded "art" from ubiquitous processes and materials? Curator: It’s an interesting point. Photography, often regarded as a "democratic" medium, nevertheless comes with its own sets of power dynamics, as do landscape photographs, with their specific gaze and focus on ownership and control. There's a push and pull between access and intentional artistic choice here, and also an evocation of the way that technology informs, and perhaps mediates, our own subjective relationship with nature itself. Editor: And let’s consider Lincoln's labor in the darkroom. The dodging and burning techniques used in gelatin silver printing allowed the artist to manipulate light and shadow. How did that painstaking process transform a “simple” photograph into something much more deliberately composed? There is something quite striking in a seemingly mundane natural composition elevated through industrial production of photography. Curator: True. His darkroom work transforms a scientific exercise into something deeply personal, almost spiritual. The single orchis is a small miracle in a dense forest, a marker of beauty existing independently, without requiring our permission, in what might seem, on the surface, a common landscape. Editor: In the end, what this work reveals is how even supposedly "objective" technologies and approaches remain firmly tied to processes of labor and intentional aesthetic production. Curator: A powerful, subtle reminder of the constant, ongoing interplay between humanity and nature.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.