drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

expressionism

Dimensions: 19 x 24 11/16 in. (48.2 x 62.7 cm) (sheet)16 7/8 x 24 11/16 in. (42.8 x 62.7 cm) (image)23 5/8 x 29 1/2 x 7/8 in. (60.01 x 74.93 x 2.22 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

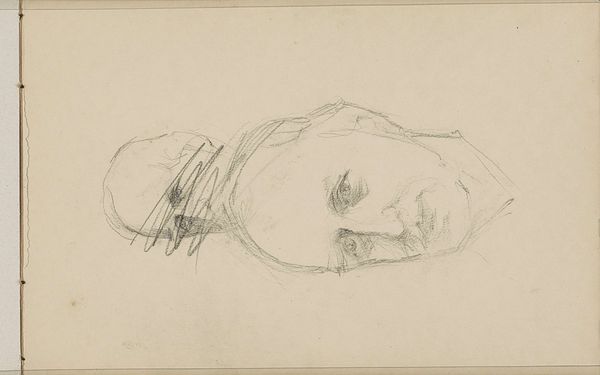

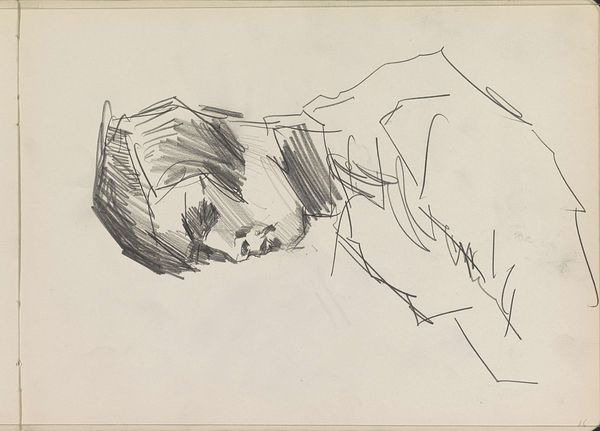

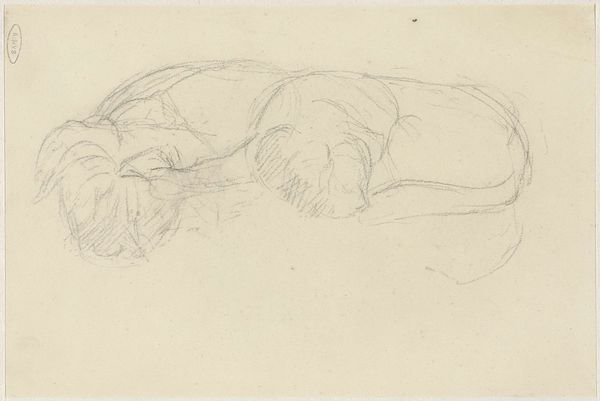

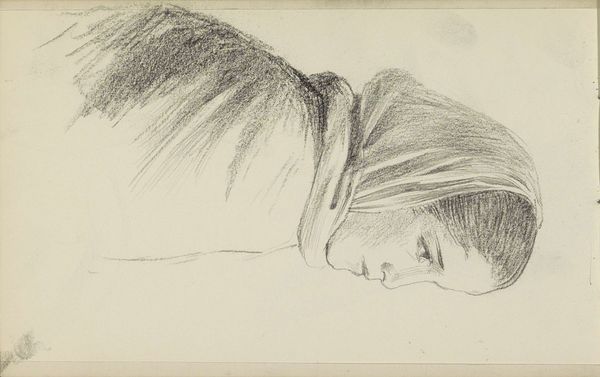

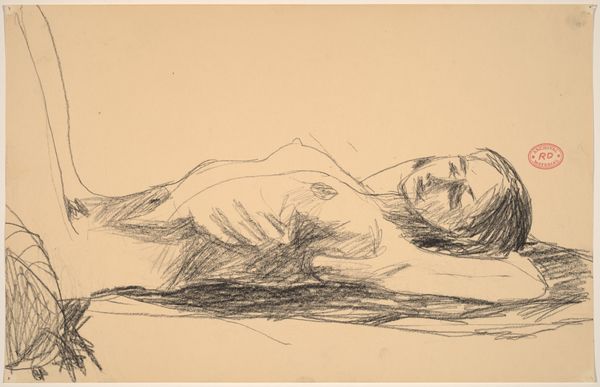

Curator: Here we have Käthe Kollwitz’s "Two Studies of a Woman’s Head," created around 1903, and residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It’s a delicate drawing executed in pencil. Editor: It's profoundly affecting, even in its quietude. The composition, the downcast faces – it feels heavy, burdened. Curator: Kollwitz's choice of pencil, a readily available and relatively inexpensive material, speaks to her commitment to portraying the working class and the realities of their daily lives. Pencil allowed for quick studies, readily reproduced. Editor: I'm struck by the use of light and shadow. See how the artist manipulates the gradations of gray to suggest the forms and contours of the faces, conveying an inner world that hints at deep thought or possibly distress? The materiality and darkness speak loudly, almost literally from the page. Curator: Indeed. Consider the broader context; Kollwitz lived through a period of immense social upheaval in Germany, with growing industrialization and urbanization. She bore witness to labor exploitation, poverty, and war, all impacting gender dynamics and labor standards. Her art became a powerful voice for the disenfranchised. These ‘studies’ served perhaps as practice or were sketches for a series to highlight these issues. Editor: It seems to me Kollwitz is skillfully contrasting the delicate rendering of the faces with the rather forceful application of lines. In doing so, a tension is produced in the drawing itself, an uneasy harmony that suggests vulnerability against a harder surface. Curator: It's interesting to ponder how this artwork might have circulated during her time. Kollwitz often produced prints of her drawings to make them more accessible. What stories did these affordable artworks carry as they entered working-class homes and community spaces? What kind of social and emotional response did this solicit, or demand, for viewers of the era? Editor: Viewing them today, that interplay between stark representation and inner emotion continues to hold our gaze, forcing us to question and reflect on themes that feel timelessly relevant. I keep thinking about line and form: this sketch achieves an enormous impact with simple methods. Curator: It underscores that art's power is found in process, intention, and its capacity to reflect and engage with societal realities far beyond its immediate aesthetic appeal. Thank you for exploring Kollwitz with me! Editor: Yes, indeed. Thank you. A reminder that great power can be found in the smallest gesture of artistry, formally considered or in terms of production value!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Käthe Kollwitz had a remarkable ability to tap our capacity for empathy. Living in an impoverished section of Berlin, she witnessed firsthand the suffering of the ill, the unemployed, the malnourished, and the bereaved. This life study showing two views of a woman’s head conveys a world-weariness that speaks across time. In the larger study, Kollwitz shifted the position of the woman’s head, emphasizing the hollowness below her right cheekbone. She used fine hatching to bear in on the terrain of the woman’s haggard face. Finally, Kollwitz selectively smeared the chalk to indicate the soft skin of the woman’s lips and eyelids, lending a touch of tender vulnerability to her tough, leathery features. Related works reveal that as Kollwitz drew this study she had in mind a mother grieving over a dead child.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.