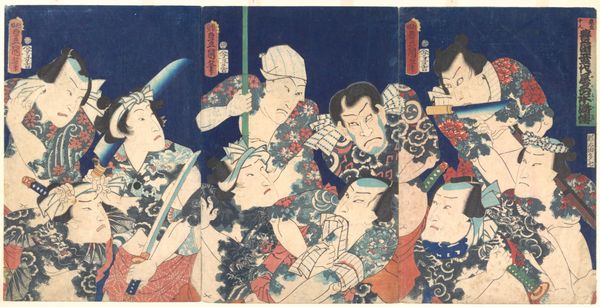

Actor Ichikawa Danjūrō IV as Sukeroku playing a game of kubiki (neck-pulling) with actors as Five Chivalrous Commoners 1768

0:00

0:00

print, woodcut

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

folk art

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 14 3/16 x 22 1/16 in. (36 x 56 cm) (image)53 15/16 x 27 3/16 in. (137 x 69 cm) (mount) 75 cm W w/roller

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Oh, wow. My first impression? Utterly absurd! I mean, just look at this peculiar scene—all these expressive faces crammed into one frame, doing… what exactly? Editor: Indeed! We're looking at a woodcut print dating back to 1768, now residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It's titled "Actor Ichikawa Danjūrō IV as Sukeroku playing a game of kubiki (neck-pulling) with actors as Five Chivalrous Commoners", attributed to Bunchō. The subject is a depiction of kabuki actors seemingly in some unusual form of contest. This is fascinating when we consider the relationship between performance, celebrity, and social commentary within the context of ukiyo-e prints. Curator: Okay, context duly noted. Still, my eyes keep going back to that central figure pulling the ropes. He seems… annoyed? Is it supposed to be playful, or is there something more subversive at play? The faces in the back suggest some mix of discomfort and mild amusement. Editor: Subversion is certainly part of the appeal. During the Edo period, Kabuki theatre and ukiyo-e prints provided an outlet for representing social desires and critiques that could not be voiced publicly. Representations of actors became inherently linked to conversations around gender, power, and even class. Given that it is the depiction of actors and performances of identities on a stage it creates a very unique opportunity for reflecting societal expectations and potentially dismantling them. Curator: Ah, so this neck-pulling game… could be symbolic of something bigger, then? The tensions between performance and reality, perhaps? Are we seeing a challenge of the status quo right there in a seemingly frivolous game? And these intense red and white colors are so attention-grabbing against the neutral ground, do you have thoughts on those. Editor: Absolutely, the use of color within ukiyo-e tradition plays a pivotal role. The contrasting colors underscore the drama of the situation—it accentuates the emotional extremes, and I suppose that is what performance art tends to create by over accentuating. Curator: It is also a reflection, if those extreme emotions don't find a medium like this they get to stay under the radar for long, it takes courage to be exposed. Editor: Indeed, even from afar, we can glean an insight into this form of artistry in 18th century Japan and how it serves the important role of subverting narratives and the mainstream at the same time, and with playfulness too! Curator: Definitely. This image really sparked something. And it will probably stick in my mind for days… It's like it created this sense of unresolved, playful yet complex conflict!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Related to the play "Ayatsuri kabuki ōgi" (Mastery of the Fan in Kabuki) performed at the Nakamura Theater in the seventh month of 1768. The five actors on the right are the Five Chivalrous Commoners that performed in one act of this play: Arashi Otohachi I (1711-1769) as Hotei Ichiemon, Matsumoto Kōshirō III (1741-1806) as Gokuin Sen'emon, Nakamura Sukegorō II (1745-1806) as Kaminari Shokurō, Ichikawa Komazō II (1737-1802) as Karigane Bunshichi, and Ichikawa Yaozō II (1735-1777) as An no Heibei. Originally attributed to Katsukawa Shunshō, the facial expressions of the actors as well as the date of painting make an attribution to Bunchō much more plausible.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.