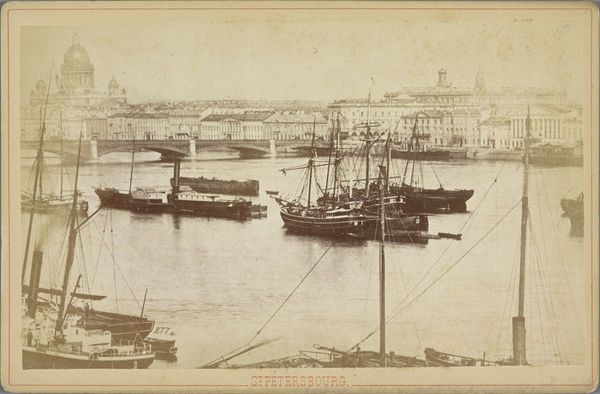

daguerreotype, photography

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Alexis Gaudin's "Brug in Rotterdam," a daguerreotype from between 1858 and 1860. There’s a stillness to this image, a calmness in the muted tones. The bridge and the ships suggest a bustling port city, but everything is so… static. What stands out to you most when you look at this? Curator: What grabs my attention is this layering of histories and industrial transformations frozen in a moment. The daguerreotype process itself—a cutting-edge technology in its time—is capturing Rotterdam at a pivotal juncture. Think about the labor embedded in these scenes: the dockworkers, the sailors, the industries dependent on this port. Editor: It’s easy to forget the human element when you see a scene like this from so long ago. Curator: Exactly! And that's where engaging with theory becomes essential. This isn't just a picture; it’s a document of social stratification and a burgeoning capitalist system. What about the colonial implications of a busy port? Where are these ships traveling to and from, and what’s being transported? We need to consider those power dynamics embedded in global trade. Do you see hints of that reflected here, in the relationship between architecture and vessel? Editor: That’s… a lot to unpack from one photo. I was just looking at the pretty reflections in the water. Curator: But even those "pretty reflections" can become tools for questioning. Is the shimmering surface concealing deeper societal currents, maybe? Or mirroring the aspirations and anxieties of a city undergoing rapid change? Editor: I never thought about it like that. It adds so many layers to the image. Curator: Precisely! Art, even early photography, isn't created in a vacuum. Engaging with its context allows us to understand how it reflects and shapes the world around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.