Dimensions: image: 1199 x 799 mm support: 1207 x 807 x 1.5 mm support, secondary: 1207 x 807 x 1 mm frame: 1218 x 817 x 40 mm

Copyright: © Richard Long | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

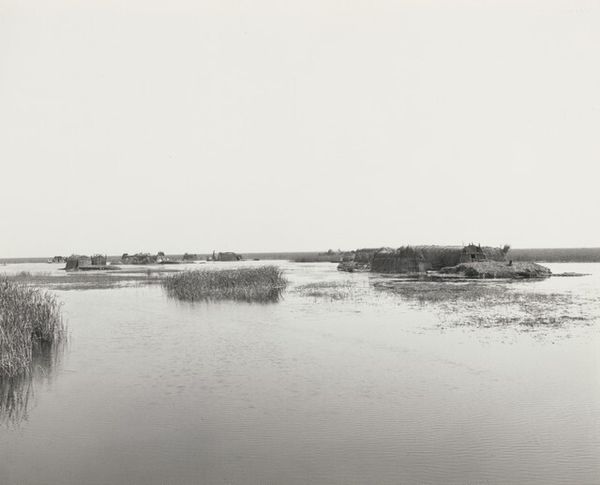

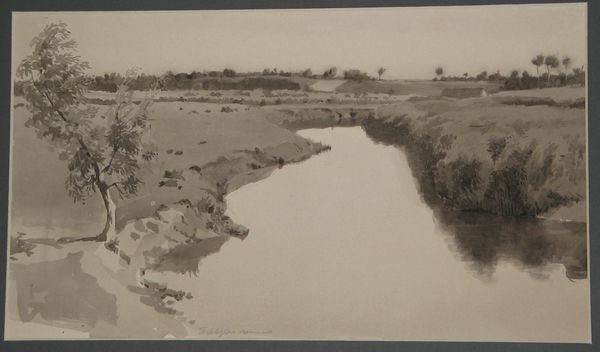

Curator: Richard Long’s "Waterlines," captures a landscape in Maharashtra, India. It's a compelling image. Editor: There's a starkness to it, a washed-out quality that feels both ancient and immediate. Curator: Long often explores the relationship between humans and the natural world. This photograph documents a place, but also a cultural interaction with the land. Editor: The waterlines themselves create a sort of primordial script across the stone. They remind me of nature's own language etched onto the earth. Curator: It's a document of place but also Long’s place within that landscape. He’s showing us both the physical reality and the cultural significance. Editor: It’s as if the water itself is a symbol of time, a constant, eroding force that shapes both the land and the lives lived upon it. Curator: Understanding it now, it really encourages a deep reflection on human impact on landscapes. Editor: Yes, the photograph whispers about endurance, about adaptation, and about the silent dialogue between humanity and nature.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 3 months ago

⋮

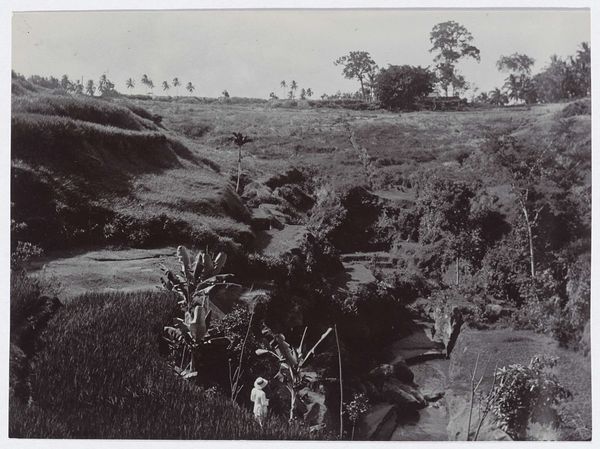

Since his earliest practice, begun in the late 1960s, Long has based his art on the action of walking in the natural landscape. With his seminal work, A Line Made By Walking 1967 (Tate P07149) – a photograph showing a straight line worn in a field of grass by the repeated movement of the artist’s feet over it – Long established the simple act of walking as a gesture of primordial mark-making fundamental to the creation of art. In the context of late 1960s conceptualism, Long’s act may be seen as a subversion of the traditionally expressive gesture central to painting. Walking is non-expressive, a mechanical movement which permits the body to travel from one point to another. In a similar way, the line joining one point to another is fundamental to the process of drawing – a way of expressing direction and the logical means of connection on which cartography is based. Lines imposed on the environment are usually the result of processes of measuring, map-making and creating roads and are forced by the contours of the earth’s surface to compromise the ideal logic of straightness. Since the 1970s, Long has extended the straight line to encompass the cross, the square, the circle, the spiral, the ellipse, the curved line, the crooked line, the zig-zag, concentric rings, parallel lines, the heap, the dribble, the scratch; every possible means of making marks in nature with what is to hand, using simple actions with the artist’s hands or feet, is covered in Long’s oeuvre. More recently he has gone full circle with the notion of mapping and the trajectory of a body (in this case a body of water) through the landscape by tracing the pathways of rivers and recreating them, much reduced in size, out of gravel or stones.