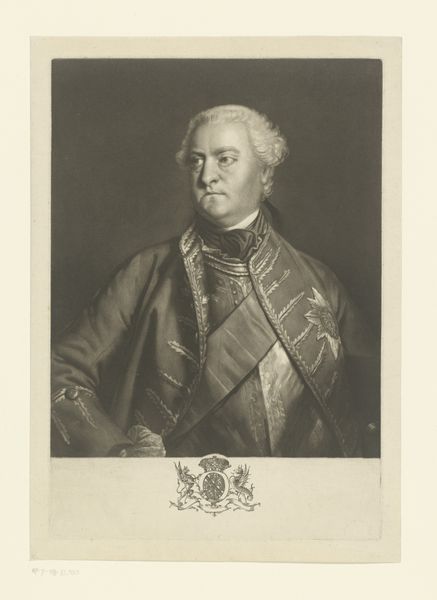

Portret van Lodewijk Ernst, hertog van Brunswijk-Wolfenbüttel 1738 - 1792

0:00

0:00

aertschouman

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 327 mm, width 237 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Lodewijk Ernst, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel, crafted between 1738 and 1792. It's an engraving, so a print made from an incised plate, by Aert Schouman, currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first thought? Heavy. Not just the dude himself, but the whole feel of it. It's like he's weighed down by all those velvet robes and powdered wigs. Almost makes you want to reach in and offer him a cup of chamomile tea, or maybe a therapy session. Curator: I see that immediate interpretation, and it aligns interestingly with Lodewijk Ernst's historical positioning. His appointment as advisor to Stadtholder William V was deeply controversial. His German background stirred xenophobia, leading to perceptions of undue foreign influence. Editor: Xenophobia, huh? See, there's something in the stiff posture and those somewhat wary eyes... it hints at the outsider trying to project authority. Makes you wonder about the social pressures he faced, right? All that performative power, but maybe he was just trying to belong. Curator: Exactly. His image became a focal point for political dissent. Anti-Orangist factions used his presence to attack William V, questioning the Stadtholder's decisions and eroding public confidence in the regime. The print itself, therefore, becomes part of a wider visual discourse about power and legitimacy. Editor: The rendering here is so precise! Like he's immortalized on paper. Is this how he thought of himself or someone else's rendering? Was he comfortable? Also, it makes me think: How complicit was the artist in this political theater? Was he making a neutral copy, or did he have a point of view he embedded there, in the choice of shadow, the slight downturn of his lips, anything? Curator: These are potent questions that intersect the fields of art and political history, yes. As you notice, the artist captures the duke in this sort of severe grandeur. You are compelled to consider what he represents—both in terms of aristocratic power and in terms of the societal fractures of the time. How art becomes propaganda. Editor: That weightiness I felt isn't just aesthetic, is it? It’s the weight of a whole socio-political structure pressing down. I definitely appreciate that new point of view about an era I thought I knew about. Curator: Precisely. And for me, it's another look at the ways that art exists in dialogue with the currents of history and public opinion, allowing us insights into forgotten lives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.