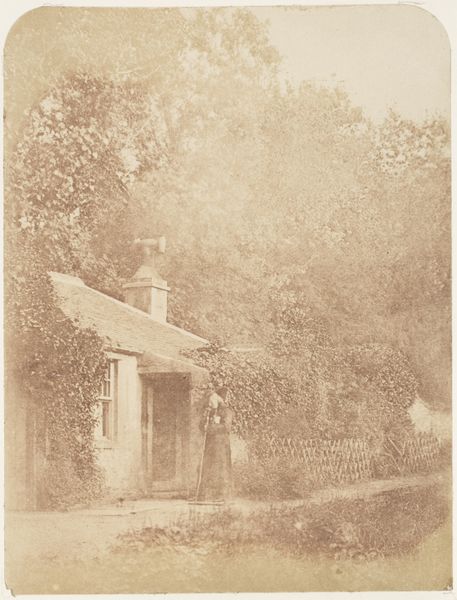

Dimensions: 11.9 × 9.7 cm (image/paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Take a look at this rather lovely photograph! "Mrs. Craik in Outdoor Garden," dating from around 1848 to 1860. What stands out to me is the very staged contrast between the laboring man with the rake, and Mrs. Craik framed passively in the doorway of what seems to be an English cottage. What kind of social dynamics might be in play? Curator: It’s fascinating, isn't it? The piece is certainly evocative of the socio-economic structure prevalent in Victorian England. Think about photography's emergence at the time. Who had access? Who was being represented, and how? A garden wasn't just a place for leisure. It reflected a family's status, wealth, and control over nature itself. How do you read that power dynamic as expressed through gender and labor in the piece? Editor: I think what you're getting at, Curator, is how gardens reflect privilege. But couldn't we argue that photography also provided opportunities for those who weren’t typically represented in art to be seen? It democratizes representation, doesn’t it? Curator: In theory, yes, but let's look at it more closely. Mrs. Craik's deliberate placement, the carefully arranged garden, and the laboring figure– aren't these curated elements reflecting and reinforcing a certain societal order? Perhaps even reinforcing who "deserves" to be photographed and how. Whose narratives are considered important enough to record? Editor: So, beyond the surface, we're actually looking at the politics of visibility in early photography. The apparent tranquility masks layers of social and economic stratification. Curator: Precisely. Understanding that relationship changes how we see not just this image, but the whole medium itself. Editor: That shifts my perception entirely. I'll certainly look more closely at similar portraits going forward!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.