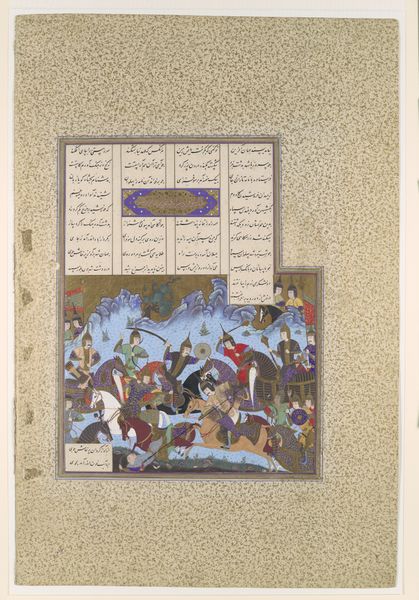

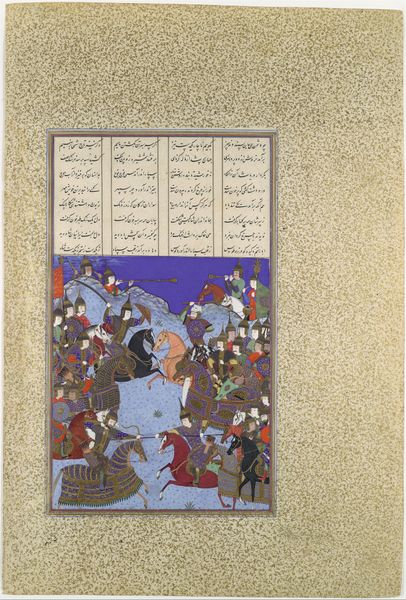

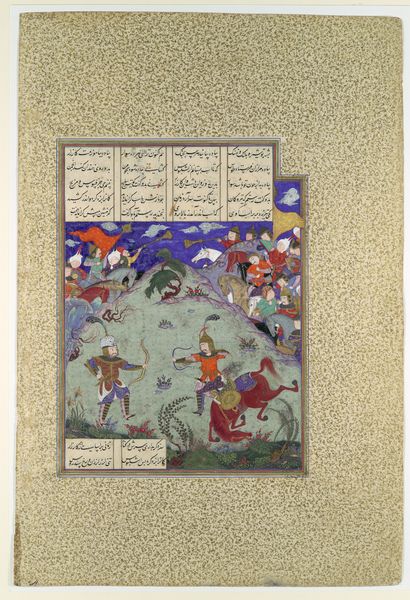

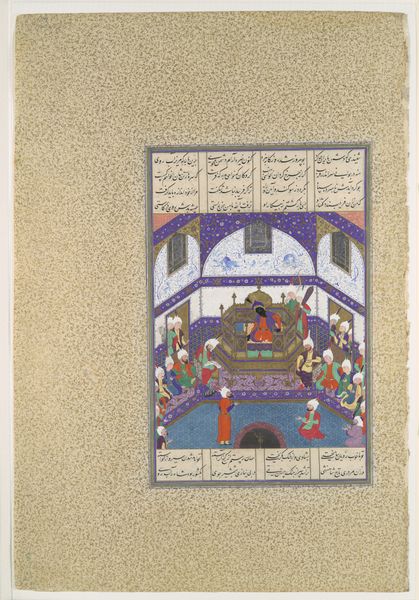

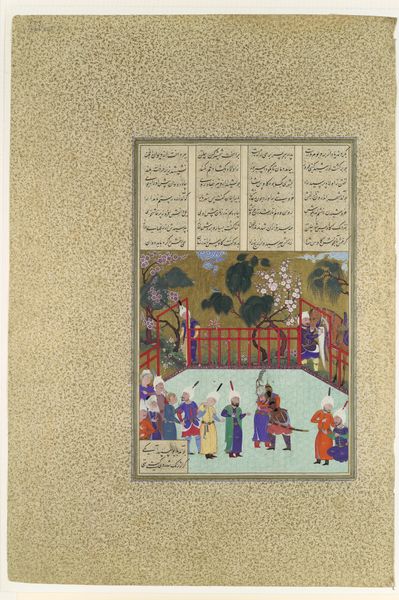

"Gustaham Slays Lahhak and Farshidvard", Folio 349v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp 1500 - 1555

0:00

0:00

painting, watercolor

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

horse

#

men

#

islamic-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: Painting: H. 6 3/4 in. (17.2 cm) W. 6 7/8 in. (17.5 cm) Entire Page: H. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm) W. 12 9/16 in. (31.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: So, what draws you in about this vibrant page from the Shahnama? Editor: This is Folio 349v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, depicting "Gustaham Slays Lahhak and Farshidvard." It was made sometime between 1500 and 1555, and the medium appears to be watercolor and coloured pencil. I’m struck by the intense energy captured in such a small format – all those horses and clashing figures! How do you read the choices made in its construction? Curator: I’m most intrigued by the collaborative labour evident here. Think about the sheer number of skilled artisans involved: papermakers producing the ground, calligraphers inscribing text, painters meticulously layering pigments. The consumption of materials is equally significant, pigments were derived from valuable minerals and plants traded across vast distances. Editor: So you see it as less about the individual artistic genius, and more about the network of making? Curator: Precisely! The vibrant colours weren’t simply chosen for aesthetic value. The procurement and preparation of pigments were deeply intertwined with wealth, power, and access to trade routes. These weren't just illustrations; they were commodities, symbols of status. Notice how even the paper is meticulously prepared and finished. It suggests this Shahnama operated within a very specific and wealthy sphere of patronage and production. What does the calligraphy mean in that context, do you think? Editor: I hadn’t thought about the materiality on such a deeper level before, and you're right, understanding the processes and labour unveils how integrated art was with larger economic systems and the availability of different media at the time. It really shifts the focus from the heroics depicted to the social fabric that made the image possible. Curator: Absolutely. Seeing the Shahnama not just as a collection of epic tales, but as a material object born from specific circumstances – that’s where its true power resides. We also start seeing how consumption has historically worked.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.