sculpture, wood

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

form

#

sculpture

#

wood

Dimensions: length 20.0 cm, width 6.3 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

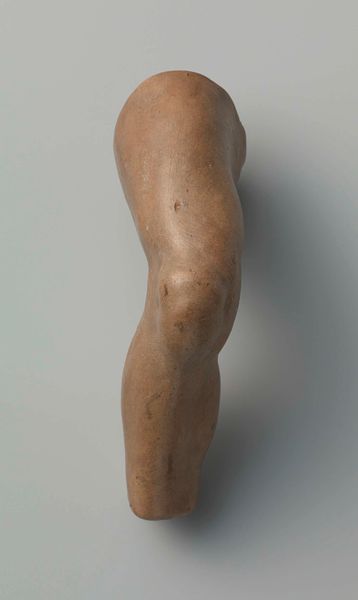

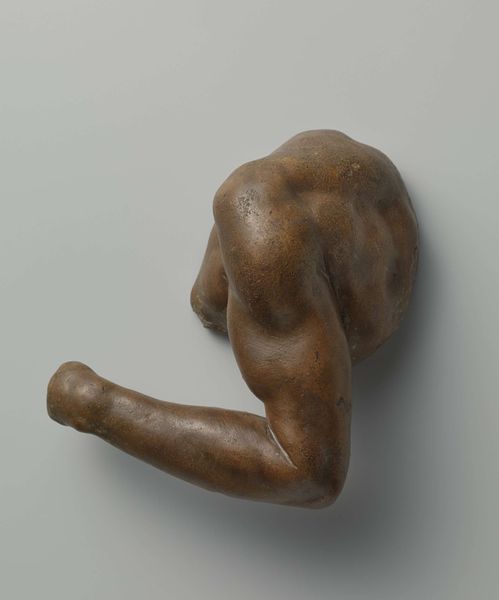

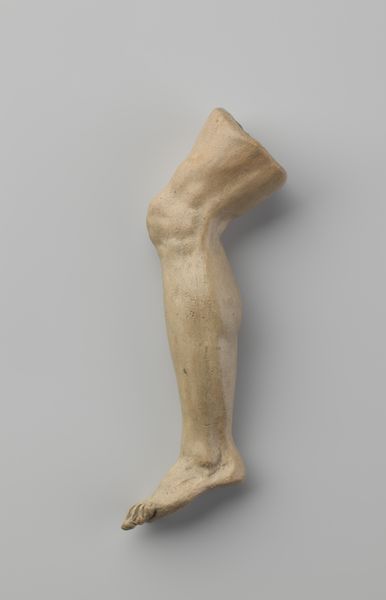

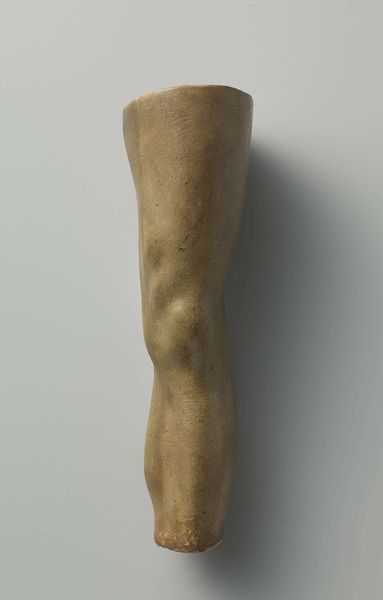

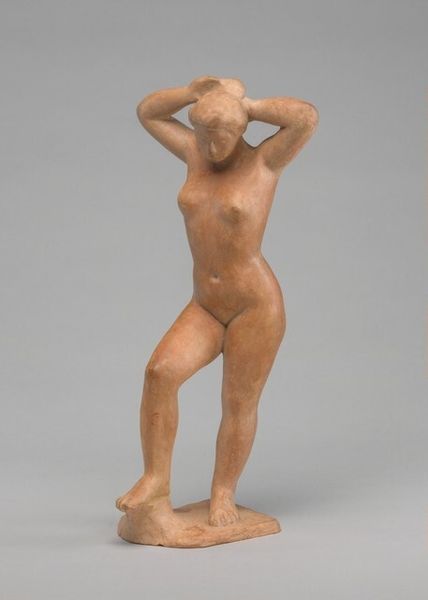

Curator: Well, this is fascinating. We're looking at "Study Models of Parts of the Body," created by Johan Gregor van der Schardt, circa 1560-1570. This piece, housed at the Rijksmuseum, is crafted from wood. Editor: It’s quite striking. The immediate impression is one of raw, almost anatomical, intensity, particularly the way the light catches the subtle textures of the wood grain. But severing the arm from the rest of the body, what does it mean? Curator: Precisely. Consider that it’s a study model, a tool for artists to understand anatomy and proportion. Its existence speaks to the artisan's hand—the selection of the wood itself, its carving and the finishing; a confluence of both labour and artistry. It is less an art object than a manual. Editor: True, but these types of objects were, and often remain, accessible only to certain classes of people. Whose bodies, then, are being studied? Who has the luxury and resources to study and produce representations like this? It invokes, for me, a conversation around privilege, power, and the male gaze—a partial figure abstracted for study, with all the attending hierarchies of knowledge production. Curator: An important point. This reminds us of the socio-economic structure of workshops and their accessibility, and also reveals trade secrets. How artisanal knowledge would often pass within a close-knit structure. The manner in which wood has been manipulated through this process, speaks volumes of time, precision, and skill. Editor: Absolutely. These works raise pivotal questions of embodiment. What does the presentation of fragmented body parts say about constructions of masculinity and the male ideal? And how did these models inform the representations of power, dominance, and heroism that filled the courts and churches of the period? Curator: Looking closely, one cannot deny how Mannerism, which thrived from 1520 to 1600, prized refinement and detail and it clearly highlights the production that enabled aesthetic beauty and a specific approach. Editor: Absolutely, and placing it within its history underscores its implications for contemporary dialogues around representation. The sculpture serves as a potent emblem of identity, and the very real cultural biases imbued through their methods. Curator: Thank you for taking us from production processes into representation, which opens up this discussion beyond this artwork's surface and speaks about the layers behind it. Editor: Indeed, an intense reflection of the intersection between anatomical observation and constructed ideals of human representation, isn't it?

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

This group of small models of parts of the body are carefully copied after famous sculptures, in particular by Michelangelo, in Florence and Rome. They came from the workshop of the Nijmegen sculptor Johan Gregor van der Schardt, who had a successful career in Italy, Nuremberg, and Copenhagen. They are extremely rare examples of the, in part autograph, study material of a 16th-century sculptor.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.