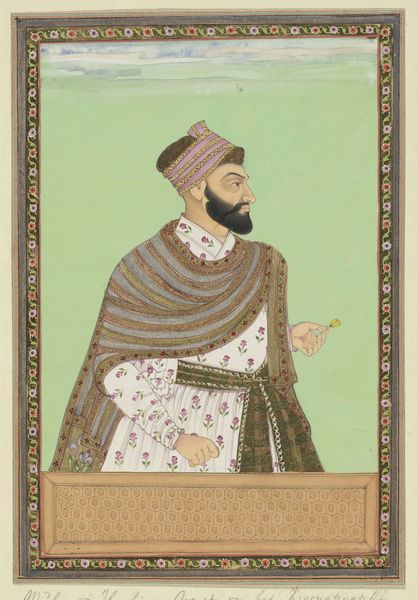

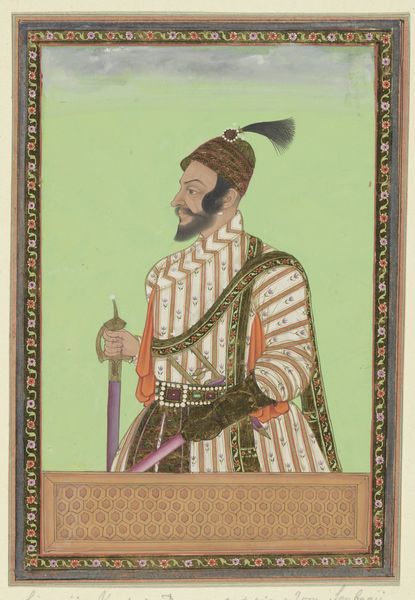

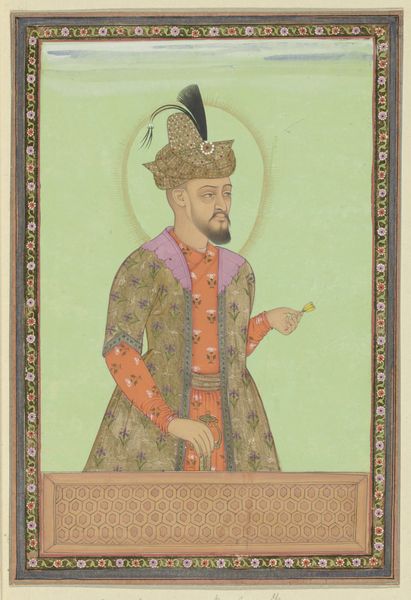

Portret van Ali Adil-shah, zoon van Sultan Mahmud; na zijn vader is hij heerser van Bijapur geweest c. 1686

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

painting, watercolor

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

watercolor

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

miniature

Dimensions: height 203 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have a portrait from around 1686, "Portret van Ali Adil-shah, zoon van Sultan Mahmud," currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. It's attributed to an anonymous artist. Painted in watercolor, it's quite intricate. It feels very formal and posed, but also richly adorned. How would you interpret this portrait? Curator: Well, I immediately focus on the materials and their socioeconomic implications. Look at the detail in the jewels, the pearls, and the gold trim in the garments. The very creation of such a detailed piece indicates available labor and access to rare commodities. The watercolor itself would have been painstakingly layered to achieve that depth. Who had access to such luxury, and who labored to provide it? Editor: That’s an interesting angle. I was thinking about the subject and his place in history. But your approach makes me think about all the unseen people involved in its making. Curator: Exactly! And consider the context in which this was created. Portraits like these weren't just aesthetic objects. They were commissioned, traded, and perhaps used as political tools. The materials and the labor invested in their display reflect power dynamics and economic realities. Do you think the choice of watercolor reflects a deliberate aesthetic choice, or simply available resources? Editor: Perhaps both? Watercolor allows for detailed work but might also have been more readily available or affordable than, say, oil paints. Curator: Precisely. The scale of the miniature allows for circulation and portability. Also, the repetition of floral design within the art piece frame is worth looking at. Editor: This has definitely shifted my perspective. I tend to focus on the subject, but looking at the "how" and "why" of its creation gives it so much more meaning. Curator: It encourages us to question traditional hierarchies – elevating craftsmanship and social awareness to be as valued as historical significance or artistic talent. Editor: Thanks for the new insights! Curator: It's been a pleasure; considering the conditions of art production always enriches our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.