photography

#

portrait

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

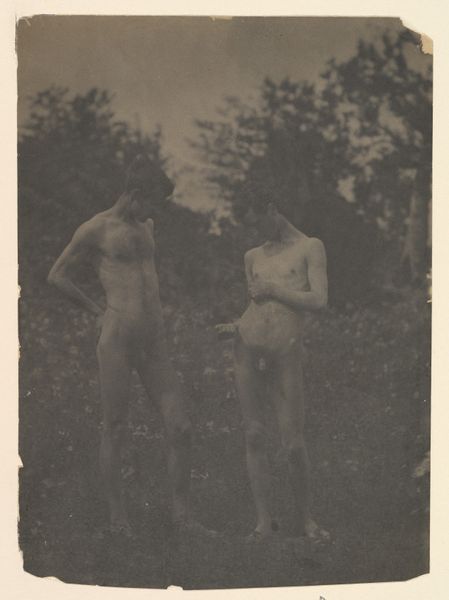

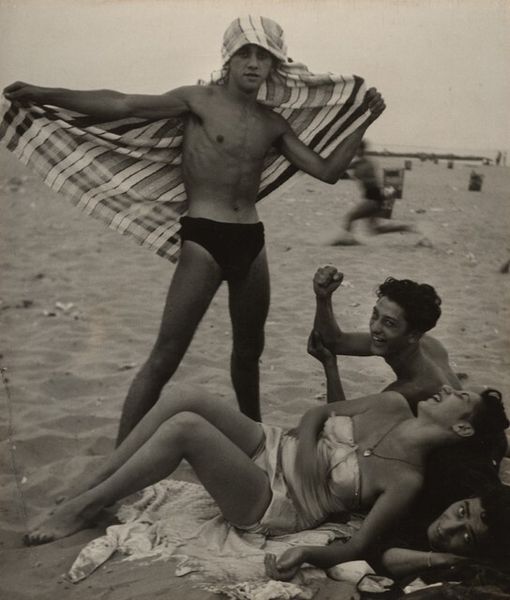

nude

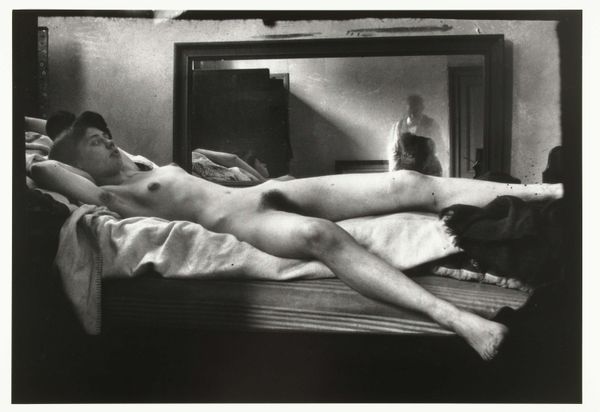

Copyright: Elliott Erwitt,Fair Use

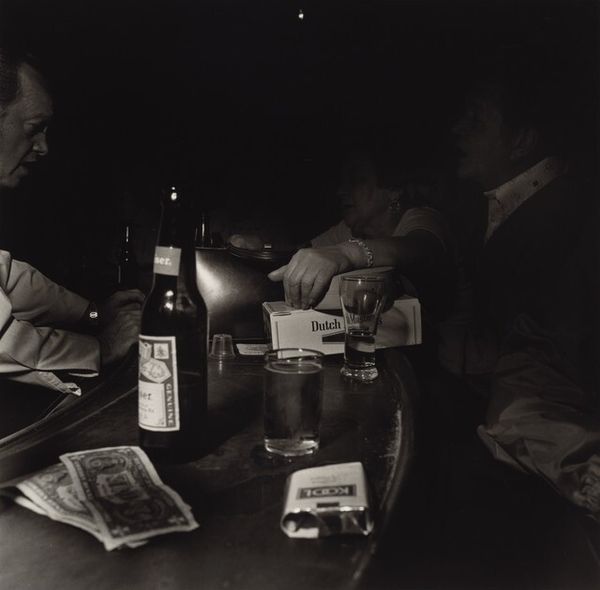

Curator: We're looking at Elliott Erwitt’s photograph "Kent, England" from 1968, a monochrome image from his street photography series. What strikes you immediately? Editor: The absurdity of it all! The ordinary and mundane juxtaposed with complete nudity. There's a formal garden behind them. They are on a raw, wooden bench, which emphasizes their bodies' vulnerability and unadornment. Curator: Absolutely. Erwitt had a sharp eye for these social commentaries. I'm drawn to how the man holds his cup, almost defensively. It speaks volumes about performativity, societal expectations of the male body, even in private. Editor: I see that tension. It feels performative, unsettling. What’s interesting to me, beyond the immediate shock value, is how Erwitt's work subverts ideas of what makes an "acceptable" subject in fine art. These people probably used to work the ground and fields where they now sit. Their nudity becomes tied to their materiality. It reminds me a little bit of the documentary "The Gleaners and I," how it considers the labor involved in making images. Curator: It also brings up questions about the accessibility of leisure for all. What does this idyll cost? And for whom is it readily available? Class is inevitably present here, particularly if they are using knitting to perhaps add financial value or create clothing for themselves. Editor: Very interesting point. The setting in Kent, historically an agricultural region, only reinforces that the backdrop isn’t just scenery. What’s discarded here on the ground with their clothing versus that pristine English backdrop shows an uncomfortable class division, a real and a visual separation of labor and ease. Curator: And considering photography's history—how it democratized portraiture while also perpetuating its own kind of elitism. Do we see an image capturing truth here, or constructing its own story? How much power do we as viewers possess looking into that intimacy? Editor: Photography holds up an ambiguous mirror to society. Seeing labor explicitly represented this way pushes us to reflect on its social cost beyond an aesthetic lens. The subjects’ nudity complicates the idea of privacy, making it more raw and present. It feels like we're intruding upon labor. Curator: A profound intrusion, precisely. The image creates friction, highlighting the distance and often awkward negotiations involved when viewing intimacy as both private and socially conditioned. I agree: an essential complexity. Editor: It’s an example of how the best artworks—especially those that consider the mundane—force us to see not just what's in the frame, but what constructs the very conditions of how and why that frame exists.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.