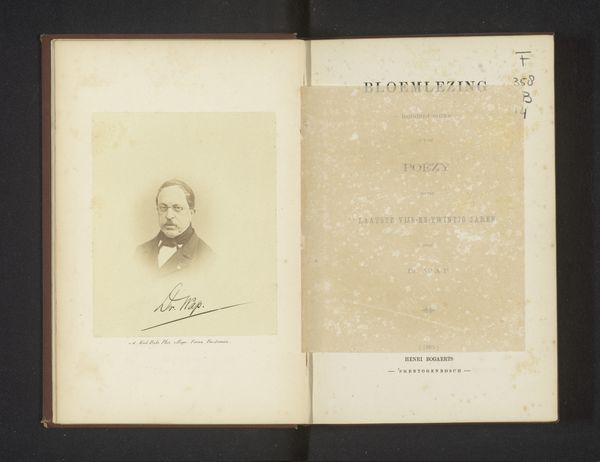

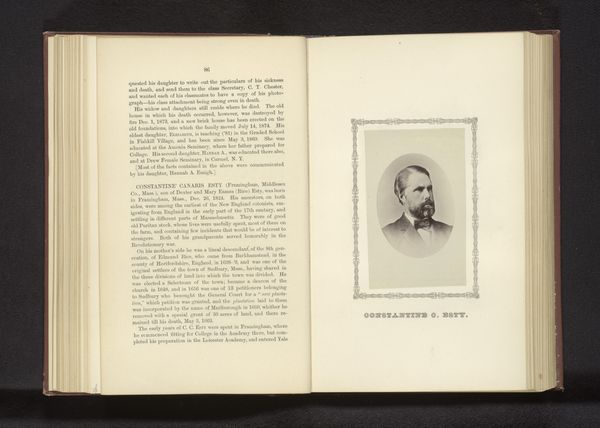

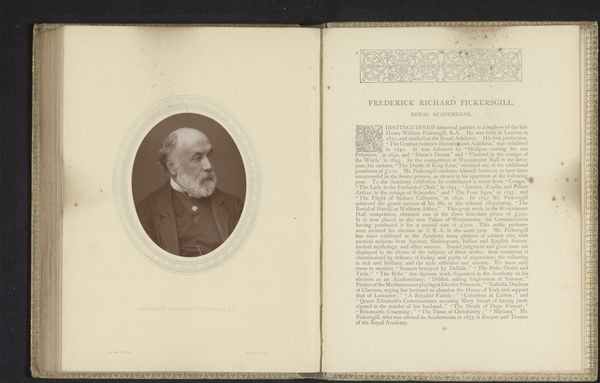

Reproductie van een foto van een portret van Félix van den Branden de Reeth before 1858

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a reproduction of a photographic portrait, dating from before 1858, depicting Félix van den Branden de Reeth. The artist, Henri Borremans, captured this image through etching, engraving, and printing it on paper. What are your first impressions? Editor: My first thought? That man looks *intense*. The portrait itself feels very contained, very formal, like he's presenting a particular version of himself. But it's hard to get a true sense with so much dark clothing set against that plain background. He appears so serious and his dark eyes really stand out, even in a monochrome print. Curator: I see what you mean. It makes me wonder, though, about what Borremans intended to convey. Considering the time, creating such a lifelike portrait would have been technically impressive, of course. Did Borremans aim for pure representation or something deeper, some aspect of the sitter's character? Editor: I'd say it's deeply entwined with social positioning. This guy was a Baron, after all. This feels very much like image crafting – reinforcing social status. And the "realism" we associate with this period—portraying individuals as they were—had political implications. Who got their portrait painted, printed, remembered? These things always reflect existing power structures. Curator: That’s such a key point. This wasn't just capturing a likeness. Each of those carefully etched lines tells a story about class, status, and the very idea of representation in that era. Still, something about those eyes, there's something questioning there that piques my curiosity and makes me feel like the picture is more than what's obviously visible at first glance. Editor: I appreciate you picking up on that human element—the potential for complexity. Still, while trying to avoid a totalizing analysis, it is equally critical to consider the means of image production at that time—who had access and who was systematically excluded. That image then exists today carrying a legacy that we must actively grapple with, critique, and deconstruct as well. Curator: Absolutely. It makes you consider what a twenty-first-century portrait looks like! What a fascinating figure; I’m really eager to investigate his story further. Editor: Indeed. I'm walking away thinking about whose stories remain untold. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.