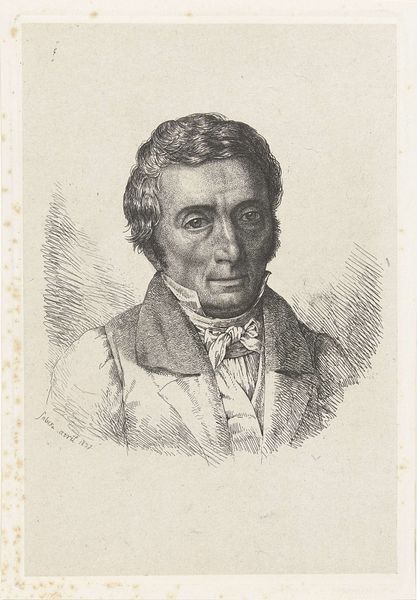

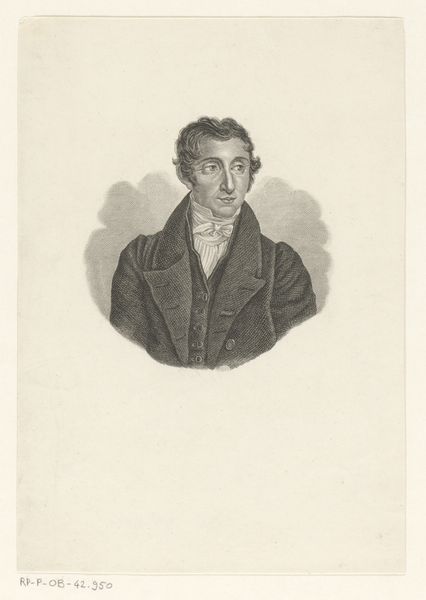

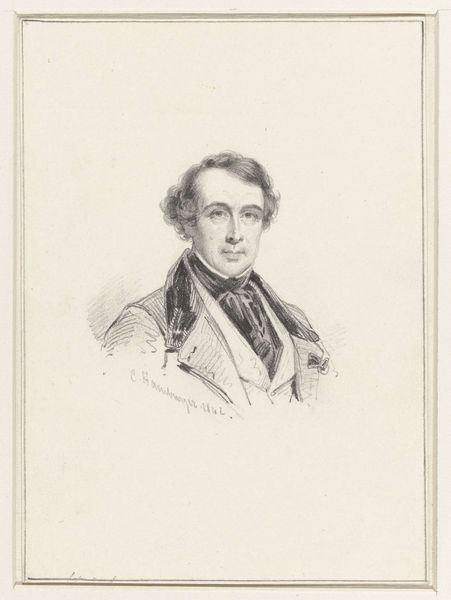

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 127 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this engraving, a self-portrait of Frédéric Théodore Faber from 1837, held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? Austerity. There's a certain reserved quality to it, a directness in the gaze. The limited tonal range heightens that sense of... almost melancholy, wouldn't you say? Curator: Indeed. Faber lived during a time of considerable social and political upheaval. While Romanticism often idealized emotion, its intersection with Realism also prompted artists to grapple with the realities of everyday life, reflecting a changing social landscape. This self-portrait might suggest the introspective nature fostered by such a period. Editor: The lines are so controlled, precise. You see that meticulous hatching creating the shadows? The way he defines his facial structure with such clarity. It draws your attention directly to the gaze, despite the lack of vibrant colors or dramatic lighting. Curator: And it is fascinating that Faber, as the artist, chose engraving—a print medium—to portray himself. This places him within a context of reproduction and dissemination, potentially implying a wish to circulate his image among a broader audience in an age increasingly defined by new forms of media. Editor: Perhaps an attempt to control his own representation, his legacy even? The even distribution of light adds to that sense of calm and dignity. Curator: Precisely. Self-representation during this period often intertwined personal identity with social aspirations. The choice of medium and the controlled, almost restrained, emotion may indicate Faber's desire to portray himself in a manner befitting his status or aspirations within society. The detail in his clothing shows the attire of the time while he is clearly posturing as an intellectual. Editor: I find the overall composition really focuses your attention to the man himself. Curator: I agree; Faber’s choices tell us so much about the social function of portraiture during this time. Editor: Yes, quite striking how much analysis emerges from such an outwardly simple print. Curator: A wonderful example of how technical skill and the pressures of socio-cultural position shaped art of the era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.