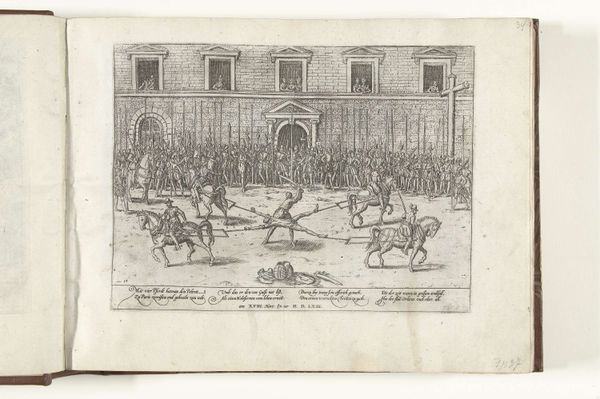

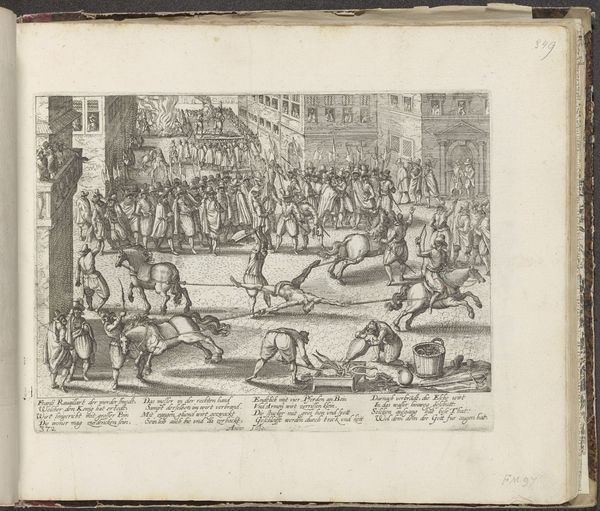

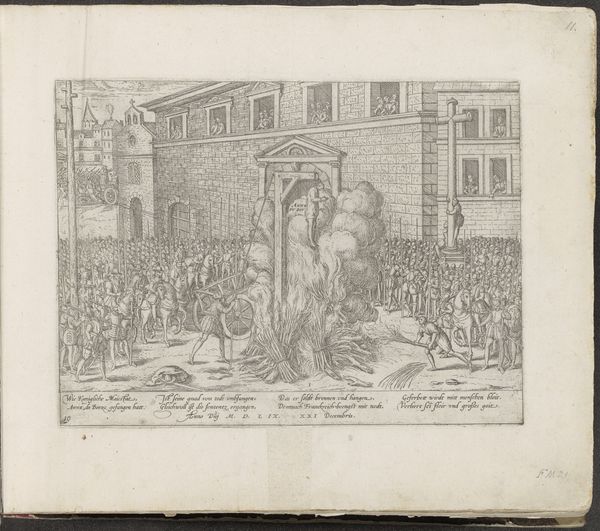

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

perspective

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 207 mm, width 279 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this rather graphic print titled "Jean de Poltrot gevierendeeld, 1563" made circa 1567-1571 and attributed to Frans Hogenberg in the Rijksmuseum, my first thought is, what a chilling scene to witness. The cross-hatching in this engraving lends it an immediacy as if we were hurried spectators at an execution. Editor: The composition does give that sensation, doesn’t it? It's all meticulously rendered. The artist certainly makes clear where power lies here. But, beyond just an image of suffering, it’s clearly charged with iconographic and emotional importance. The artist captures not just the spectacle of punishment but its socio-political ramifications. Curator: Precisely. Jean de Poltrot, a nobleman, assassinated the Duke of Guise, a leader of the Catholic party. His method was brutal: quartering. Horses pull the limbs of the condemned while crowds fill the open courtyard. Notice the cross on the right; what does that mean? Editor: Ah, but observe how distant that cross appears, almost relegated to a formal compositional device. In its place we see the dominance of the secular architectural structures towering behind. It almost screams state-sanctioned justice. Note too how even the act of quartering has a structured theatricality—almost akin to a staged morality play for its era. This resonates within us even today—capital punishment retains an inherent stagecraft intended to elicit public reaction. Curator: A performance, yes. A rather unsettling observation when one considers it, especially through the lens of the history paintings the work tries to emulate. Does Hogenberg suggest through stark visual language the transition from sacred law towards a human judicial framework? Editor: I believe that's absolutely part of it. Hogenberg's image embodies and depicts profound transitions—not merely depicting brutality, but illustrating a shift of authority within a society wrestling with faith and state. That image is also preserved, memorializing not just a brutal act, but solidifying a social order for future observers. It's a tool for shaping historical memory. Curator: Indeed, as viewers centuries removed from the context, our interpretations can still feel so layered, perhaps still grappling with the moral ambiguities represented through its symbolism. Editor: I completely agree. "Jean de Poltrot gevierendeeld, 1563" delivers a window not just into a grim event but showcases how societies actively use spectacle and representation to define the parameters of power. It invites ongoing reflection on this ever-present tension, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.