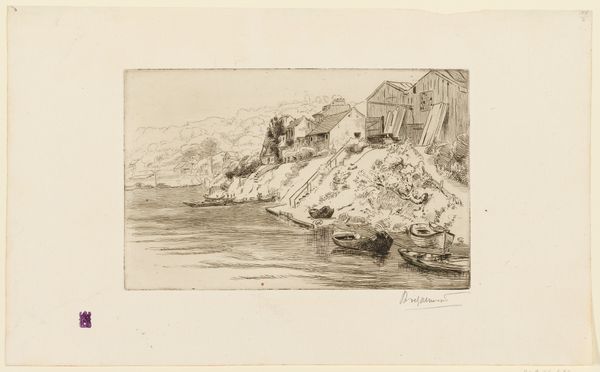

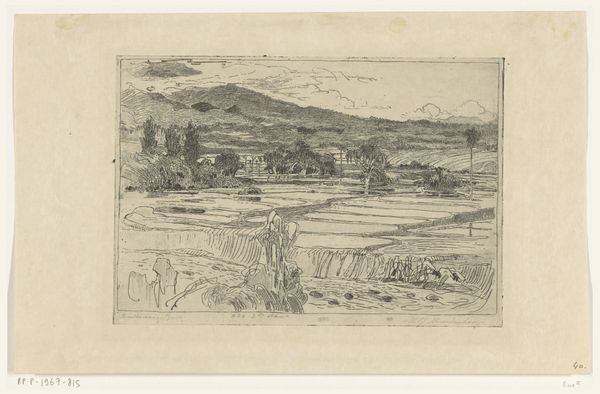

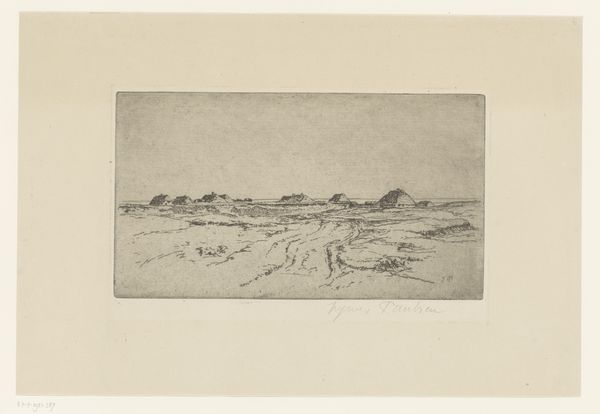

Ruiter en voetganger bij een boerderij 1799 - 1874

0:00

0:00

hendrikjozeffranciscusvanderpoorten

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

Dimensions: height 45 mm, width 68 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Hendrik Jozef Franciscus van der Poorten's "Ruiter en voetganger bij een boerderij," an etching from somewhere between 1799 and 1874. It's a humble rural scene, isn’t it? Peaceful, but almost…banal. What do you make of its quiet appeal? Curator: It's a great observation. Think about the socio-political context in which such a seemingly simple landscape would be viewed. During the 19th century, with rapid urbanization, these idealized rural scenes become increasingly potent symbols. They’re not just pictures; they represent a yearning for a disappearing way of life. Who would have had the most access to these landscape artworks, do you think? Editor: I imagine that more wealthy and urban individuals were the consumers of this artwork. They likely wanted a reminder of the traditional landscapes they did not often see. Curator: Precisely! These images reinforced certain cultural values. They championed simplicity and connection to nature, ideas that were palatable and even useful for the upper classes navigating societal shifts. Consider how landscape painting in general gains prominence at a time when the traditional land-based power structures are being challenged. Is it mere coincidence? Editor: So you're saying that the act of creating and viewing landscapes during this period was a subtle assertion of power and an idealized social order? Curator: Exactly. The "peaceful" landscape masks the social and economic changes happening. The print allows a nostalgic escape but also indirectly comments on a social structure. Think about who controls the land, who owns the "boerderij," and who has the leisure to admire the view. Editor: That gives me a whole new way of looking at seemingly straightforward landscape art. Curator: It shows that art always reflects the culture and social landscape it exists within, intentionally or not. And questioning that dynamic helps us see art – and our own world – more clearly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.