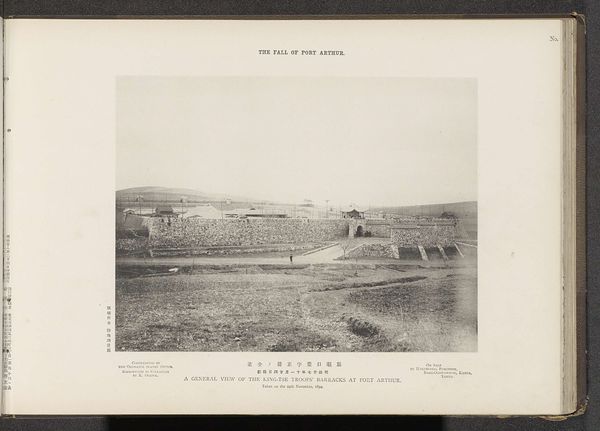

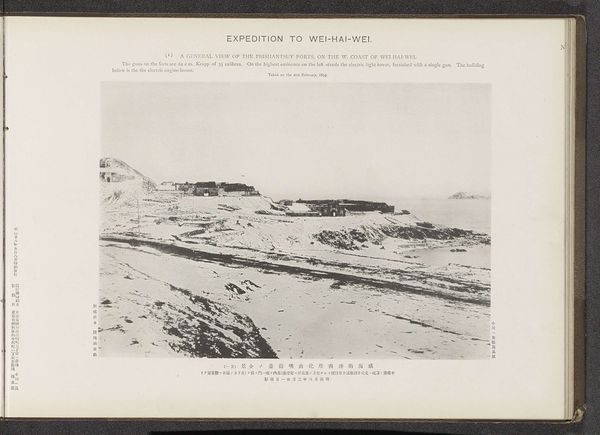

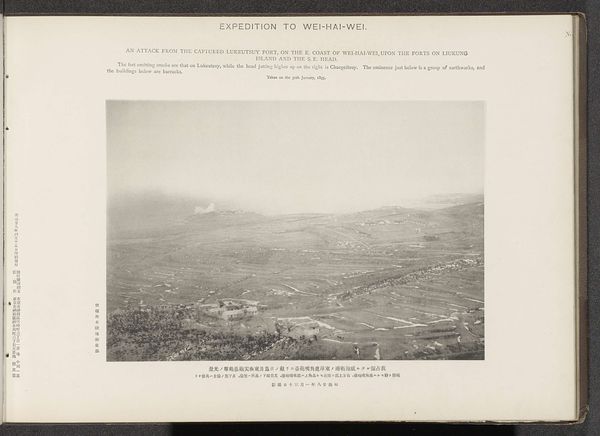

A general view of the Lungmeaoutsuy fort, on the E. coast of Wei-Hai-Wei, destroyed by the Japanese army Possibly 1895

0:00

0:00

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

history-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 285 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have what looks like a photograph – "A general view of the Lungmeaoutsuy fort, on the E. coast of Wei-Hai-Wei, destroyed by the Japanese army." Probably taken around 1895. It's pretty stark, a ruinous landscape… very heavy, somehow. What catches your eye? Curator: It's true; devastation can be rather heavy. The image almost breathes with loss. You know, it reminds me a little of those 19th-century photographs of ancient ruins, a kind of 'picturesque decay' meets geopolitics. What stories do you imagine lie beneath those stones, Editor? Editor: Definitely stories of conflict and change. I mean, you see the fort, or what's left of it, against this vast, empty space. What’s interesting to me is this depiction as 'history painting' -- How do we make sense of destruction? Is it beautiful, or is it cautionary? Curator: Both, perhaps. We, as humans, always attempt to take broken, dissonant realities and construct some meaning within. But does this image evoke a sense of 'Orientalism' for you, and if so, is it a superficial "style" or an important reflection of global dynamics in the late 19th century? What nuances exist between those concepts? Editor: Well, the title itself points to a Western gaze on this particular moment in East Asian history. Maybe Orientalism seeps into the image by how the scene's presented—almost like a trophy of war. It makes me question who this photo was really for. Curator: Exactly. Photographs weren't just neutral records, they were often instruments of power. Seeing that interplay helps us recognize how the "real" world is always being subtly sculpted and framed. It encourages us to ask “Why this and not that?” “For whom, and what do they seek?” Editor: It really does reframe how I look at historical images. There's a lot more going on beyond just the surface. Curator: Absolutely. It's not just a picture of ruins; it's a relic itself, loaded with perspectives, agendas, and maybe a few uncomfortable truths.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.