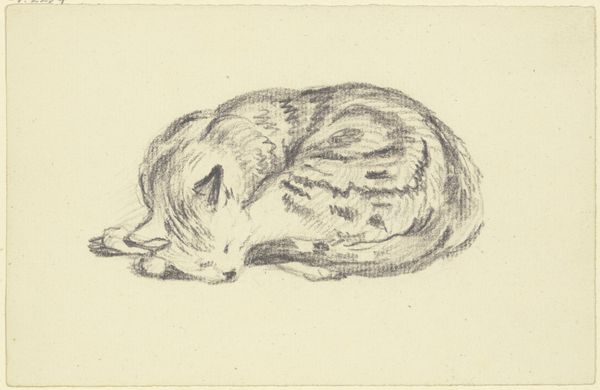

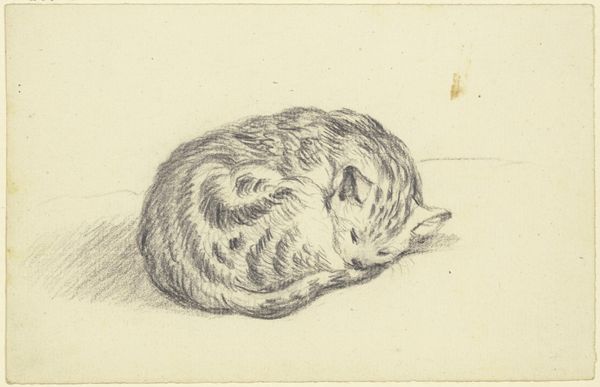

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

animal

#

pencil sketch

#

dog

#

figuration

#

form

#

ink

#

realism

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, the simple beauty of "Liggende hond" – "Lying Dog"— by Adalbertus Engelsmet, a Dutch artist who lived between 1803 and 1871. This little drawing is executed in ink and pencil. What do you make of it? Editor: My first thought? Pure comfort. It’s like visual ASMR. The density of those hatched lines suggests not just fur, but also weight, warmth... contentment. It makes me want to curl up, too. Curator: The materials lend themselves so well to that feeling, don’t they? Pencil and ink—every mark deliberate yet seemingly effortless. You can almost feel Engelsmet capturing a fleeting moment of repose. The dog isn’t posing; it's simply…being. Editor: Absolutely. And that unassuming nature gets to something fundamental about the process of realism itself— the labor it requires to create such naturalism and authenticity. Look closely, and you can see the marks building upon one another. This speaks to me of patient observation, of really looking. But beyond observation, what does that work provide materially, and for whom? Curator: A valid point! It feels so immediate, yet, you're right, one can perceive the dedication involved. The drawing speaks to me on another level, too. Engelsmet captures an essence, a spirit, of "dog-ness", beyond just representing the animal. Perhaps dogs were important for labour on a more domestic scale, guarding the farm, etc? Editor: I am drawn to the form, as much as that feeling. That tight, curled position; the line flowing from the head along the spine to the tail, back around. It feels economical. Practical even, much like animal byproducts put into use in an early nineteenth century Europe struggling for its independence from Colonial France. How would something as mundane as dog hair figure into all this? Curator: That really changes my perspective. I was focusing more on the emotional resonance, the inherent peacefulness. It is almost meditative. But I do love your weaving in the materiality of everything. It is hard to escape the practical applications of such an easily accessible animal such as dogs in this period. Editor: Well, art helps us consider both I suppose; the beautiful, and its means of production. Curator: Indeed! I am taking away the power in simplicity. In Engelsmet's close and keen observational gaze we can appreciate both the art and it's value as a form of domestic commentary and how closely animals were associated to the economics of the household.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.