#

abstract painting

#

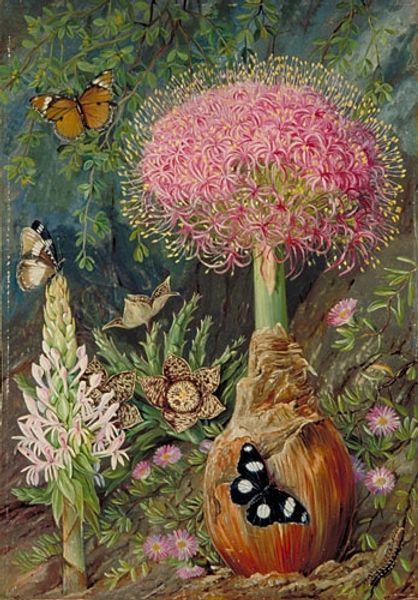

mother nature

#

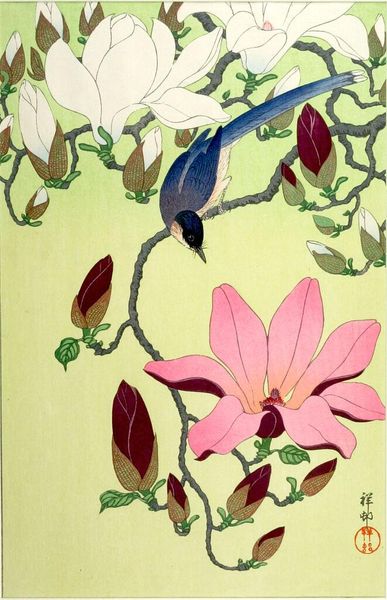

bird

#

flower

#

impressionist landscape

#

possibly oil pastel

#

fluid art

#

acrylic on canvas

#

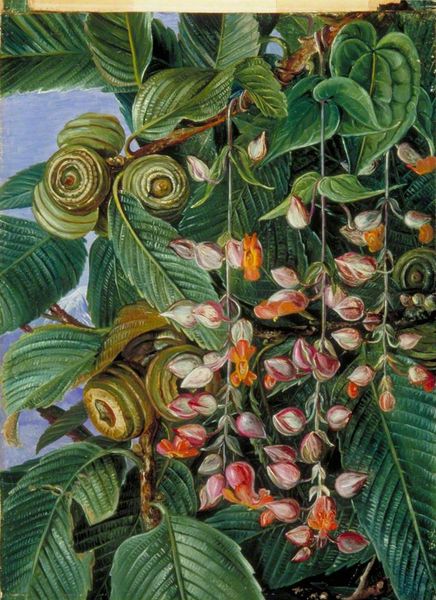

plant

#

abstract nature shot

#

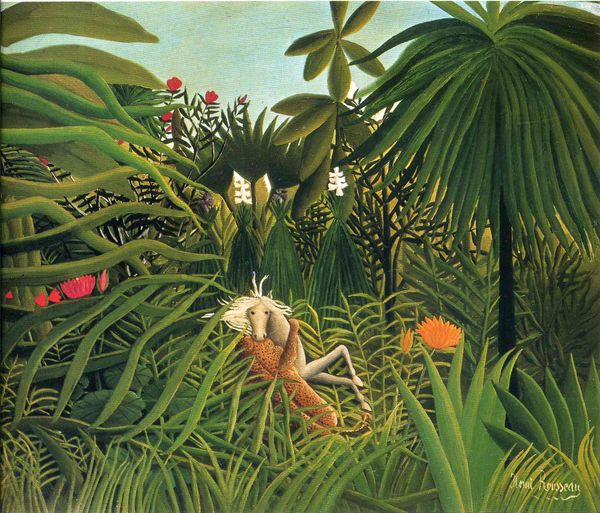

naive art

#

botany

#

natural environment

#

expressionist

Copyright: Public domain

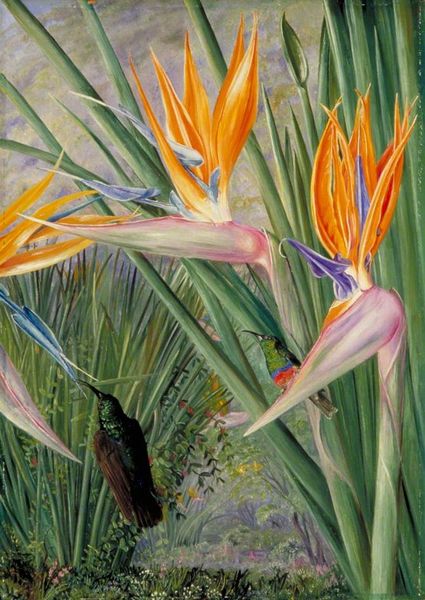

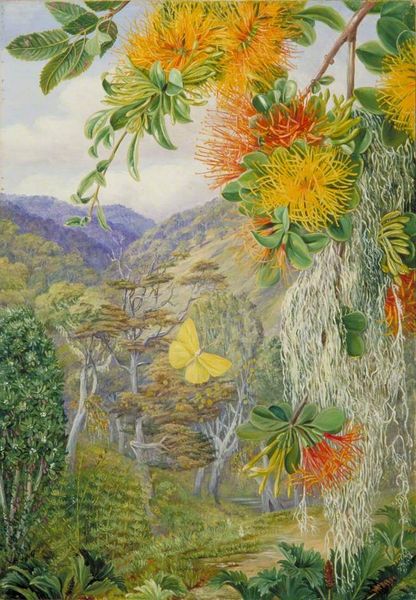

Curator: Marianne North's "Honeyflowers and Honeysuckers, South Africa," painted in 1882, immerses us in a vibrant botanical world. What springs to mind for you when you first encounter this piece? Editor: The overwhelming impression is one of dense, almost suffocating life, yet rendered with a disarming sense of meticulous detail. It makes me think about colonial botany expeditions and the drive to catalogue and contain the natural world. Curator: Yes, North was an intrepid traveler and self-taught artist, journeying across the globe to document plant life. Her work predates photography’s dominance in scientific illustration, making her canvases crucial records of global flora. Consider that North made copies of all her paintings: she was protective about access. What's captured on canvas remained somewhat within her control, a painted diorama. Editor: It's interesting to consider that 'control' given that her art materials themselves - paints, brushes, canvases - are implicated in the structures of resource extraction and production from across the British empire at that time. Did she ever reflect on this colonial paradox, the material footprint inherent in capturing these delicate botanical specimens? Curator: She did grapple with the impact of civilization on these landscapes. In her diaries, she lamented the encroachment of agriculture, mining, and the disruption of indigenous ecosystems. But it's through the art itself we sense that conflicted emotion most powerfully: the precise detailing holds almost a desperate need to save the image. Look at how the birds – those 'honeysuckers'– interact within their ecological niche in almost an erotic embrace. What I am trying to suggest, by referencing sexuality, is that each encounter with nature has consequence that exceeds the colonial context. Editor: Right, the intimate act of nectar-feeding becomes a lens through which to view resource relationships and ecological interdependence, perhaps mirroring the social and political networks in that historical context. How conscious do you think North was in reflecting those tensions between nature, production, and exploitation through the chosen iconography? Curator: Conscious is a funny word with art! It suggests intent in ways that bypass deeper unconscious motivations. What’s striking about this piece, beyond the birds and blossoms, is its tactile quality. It invites touch. What's also key is that Marianne North built her own gallery and then gifted it to Kew, a physical edifice. It's that materiality that makes all the difference. Editor: Yes, the physicality of it, the oil on wood acting as an artifact not only depicting but materially representing a moment in time, brings to bear this deeper level of understanding around networks of production, representation, and circulation, then and now. A painting containing ecological anxiety within layers of materiality. Curator: Beautifully put. North gives us a snapshot of South African flora, an insight into a critical era, but also makes us think of how paintings can operate beyond their aesthetic beauty as potent sites of memory, desire, and action. Editor: Indeed. North's image reminds us that materiality isn’t neutral; the history of each ingredient contributes to how we engage with the work—and ultimately, the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.