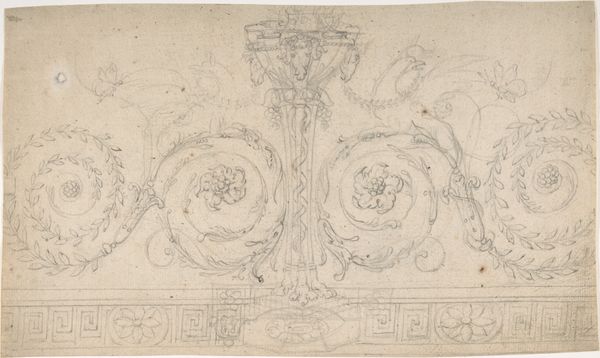

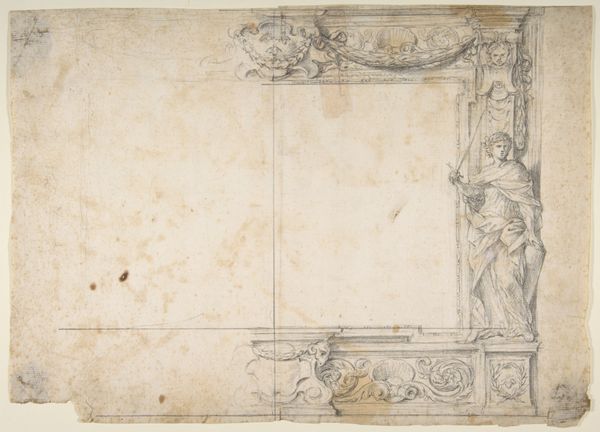

Ornamental Design after the Antique; Bands of Acanthus Rinceaux, Figurated Palmettes, and Shell Cartouches 15th - 16th century

drawing, print, ink

drawing

11_renaissance

ink

coloured pencil

geometric

line

decorative-art

Dimensions: 6 1/16 x 10 1/4 in. (15.4 x 26 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This drawing, rendered in ink, is titled "Ornamental Design after the Antique; Bands of Acanthus Rinceaux, Figurated Palmettes, and Shell Cartouches." Dating from the 15th or 16th century, its anonymous origins situate it within a rich, yet often uncredited, history of craft and design. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: The composition strikes me immediately. The repetitive bands of classical motifs – the acanthus leaves, those almost smug little faces, the shell cartouches – they create a rhythmic pattern that, despite the age, feels incredibly precise. Almost… mechanical? Curator: Interesting that you say 'mechanical.' Think about the Renaissance workshops. The division of labor meant these designs could be reproduced, influencing architecture and the decorative arts across Europe. But what sociopolitical structures enabled such widespread dissemination? Who had access to such aesthetics? And who was denied? Editor: It makes me consider the act of its creation too. A designer, most likely employed under the patronage system, carefully drafting these ornaments, potentially for reproduction on a grand scale. Were they paid fairly? Did they receive credit for their artistry, or were they merely a cog in the decorative machine? The paper itself, and the cost of the ink. Someone's hands and labor shaped those materials too. Curator: Exactly! The "after the antique" is crucial. This drawing isn’t simply ornamental; it is actively engaging with, and repackaging, classical power structures. By reviving Roman decorative schemes, European elites re-inscribed notions of empire, solidifying their own positions. Editor: And these precise lines! The labor intensity is evident. Think of the craftsman reproducing this – transferring the design to stone or wood. The hand-eye coordination. The expertise developed and likely passed down through generations within guilds and workshops. It highlights the value and cultural significance of craft itself. Curator: Yes, and the faces within these cartouches… consider who these classical features idealized. Usually, it perpetuated an incredibly narrow view of beauty, primarily white and male. This ornament wasn’t simply benign; it reinforced societal hierarchies. It's important to explore how marginalized bodies and aesthetics were excluded and rendered invisible in design. Editor: Seeing this work, knowing it was made by someone working to the specification of the antique styles, makes me so much more appreciative of contemporary makers consciously rejecting those hierarchies through their practice. Curator: Agreed. Reflecting on historical ornament reminds us that aesthetics are never neutral, especially when one considers power structures embedded in design and how crucial these kinds of pieces have been to the historical project of oppression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.