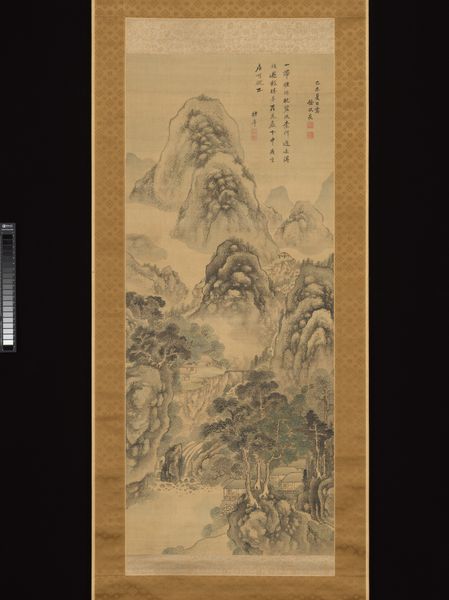

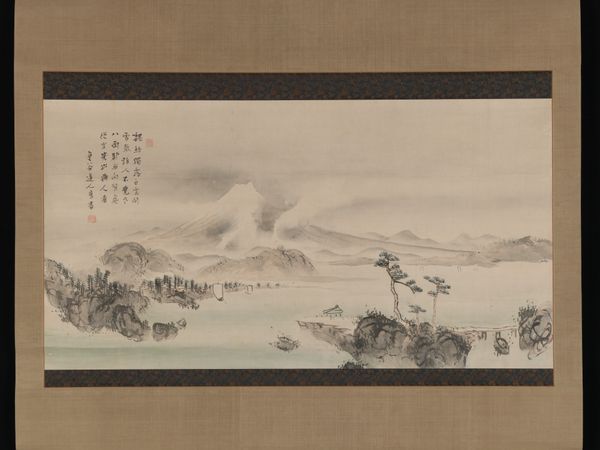

painting, paper, hanging-scroll, ink, color-on-paper

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

form

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

orientalism

#

china

#

line

#

tonal art

Dimensions: 47 x 20 3/4 in. (119.38 x 52.71 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Wang Su's "Landscape," created in 1734. It's a hanging scroll, ink and color on paper. I'm struck by the delicate linework; it feels both detailed and dreamlike. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Looking at the piece through a materialist lens, I’m interested in how the artist uses readily available materials – ink and paper – to construct an idealized landscape. What was the source of that paper? How readily available and therefore ‘democratic’ was it to artists and consumers in the region and era? Editor: That's a great point, I hadn’t considered paper as a commodity in that way. How might the availability of materials influence artistic style or subject matter? Curator: Significantly. The accessibility of ink and paper fostered the literati tradition, emphasizing brushwork and calligraphy. Artists didn't need expensive paints or studios; artistic production became more integrated with everyday life. And the landscapes – look at this one - reflect not just a natural scene, but also the owner and artist’s engagement with the materials themselves. Notice the careful modulation of ink tone; that’s about the artist’s mastery, and his time spent in meditative practice with materials. Editor: So the materials aren't just a means to an end, but actually shape the meaning of the artwork itself? Curator: Precisely! The act of creation, the labor, the very materiality of the scroll, become central to our understanding of this piece. It moves beyond just aesthetics and speaks to cultural values surrounding production, consumption, and the role of the artist within that system. And furthermore: what is being presented by a 'landscape'? Is it a document, a faithful observation? Or does it serve to reify those who own that very land? Editor: I never thought about landscape in that way. I’m realizing there are layers here. Thank you, I’ve gained a whole new appreciation for this. Curator: Absolutely! Thinking about art in relation to its means of production really opens up so many avenues for understanding.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Wang Su was a nephew of Wang Yuanqi(1642-1715) and the great grandson of Wang Shimin(1592-1680), two of the most important Qing "orthodox" painters. He was skilled in poetry and passed the first level official examinations. With the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1646, the creative impulse of literati artists surged in the wake of political turmoil and moral crisis. By the 18th century however, their successors had settled into a life of prosperity, social order and ideological conformity. A leading orthodox school was formed in Jiangsu province. Comprised of followers of Wang Yuanqi and Wang Shimin, the Lou Dong group, as it was known, was partial to the painting styles of 14th century literati masters. Like others in his circle, Wang Su declined to outwardly assert his individual identity, confining his expression to compositional clarity, exacting use of light color washes, and meticulous but unassuming brushwork. This orthodox tradition was mainstream painting during most of Qing and this classic composition by Wang is a scholarly exercise whose attraction is based on stylistic allusions to past masters like Huang Kung Wang (1269-1354).

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.