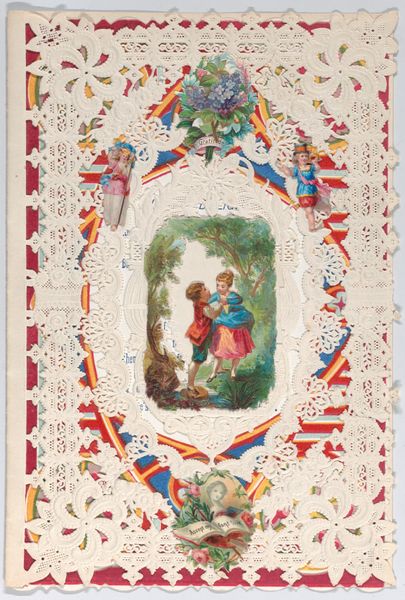

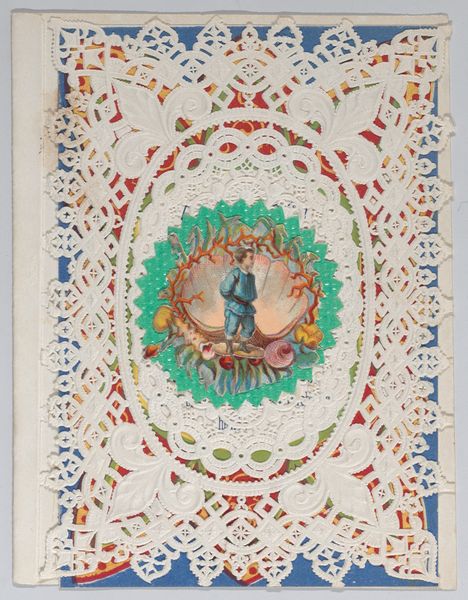

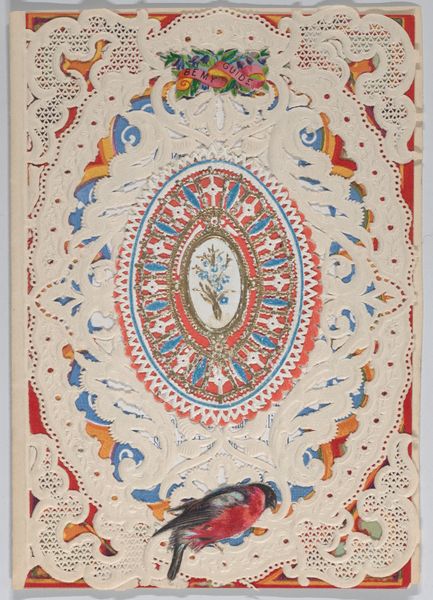

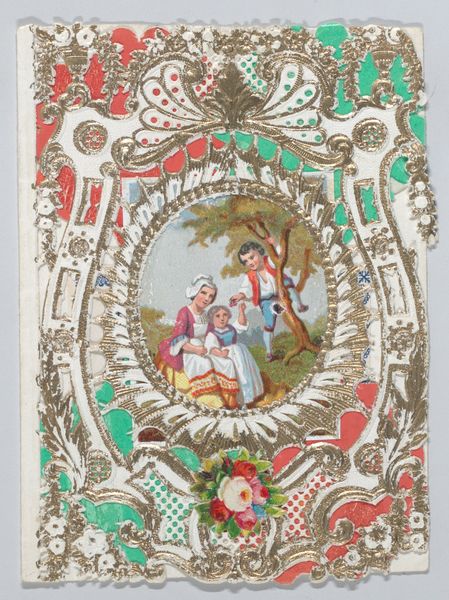

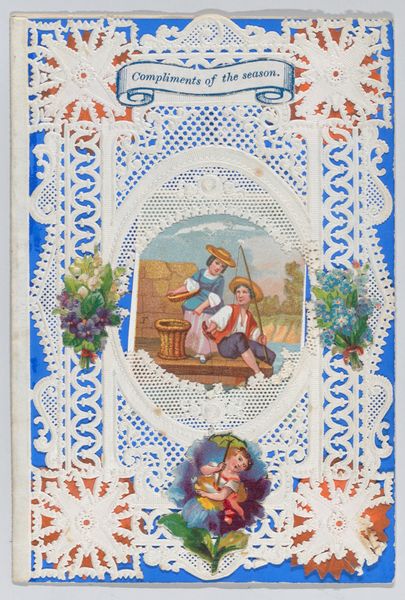

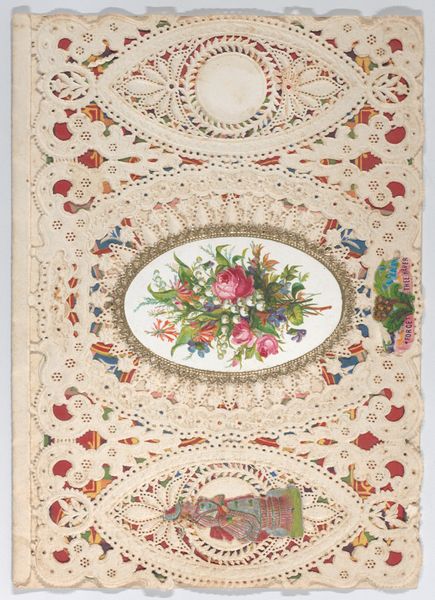

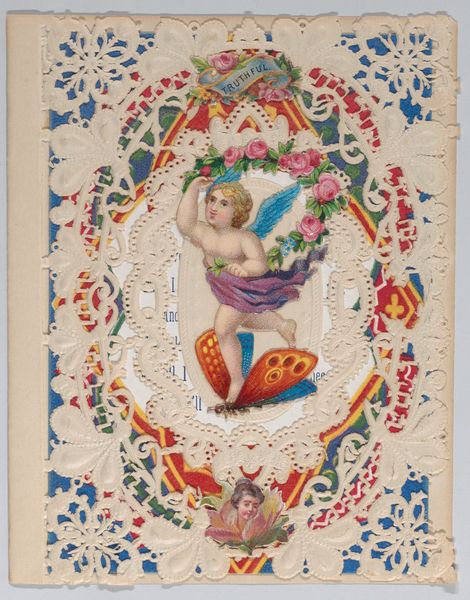

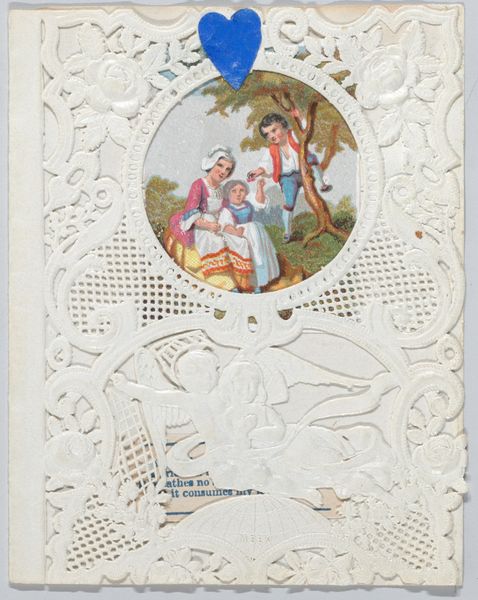

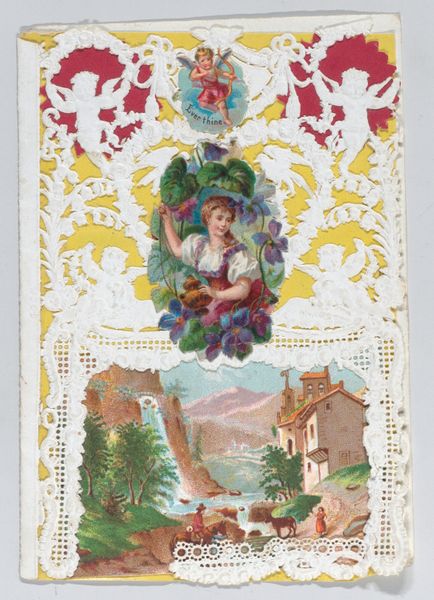

Dimensions: Width: 3 11/16 in. (9.3 cm) Length: 5 5/16 in. (13.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re looking at “Valentine,” believed to be crafted between 1845 and 1865. It is currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This elaborate greeting card is a marvelous example of early American Valentine’s Day craft. Editor: It's remarkably intricate! I'm immediately drawn to the tactile quality of all those paper cutouts. It looks almost like delicate lace, layering various textures. You can sense someone poured hours of careful labour into making this. Curator: Precisely. It gives us insight into the cultural phenomenon surrounding the mass commercialization of romance. Howland pioneered a cottage industry around these cards. She imported the paper lace, employed women to assemble them. They democratized expressions of love! Editor: Right, but let's look closer. The print work itself seems somewhat basic, right? Almost like it’s intentionally set off by all that careful hand-craftsmanship in the borders and the layered details. It creates such a tension between mass production and the handmade. Curator: That contrast is key to understanding the appeal of these valentines! Yes, while based on affordable prints, they were designed to signal personal expression. These weren’t mere trinkets but commodities imbued with sentimental meaning. Their very material construction participates in larger social performances of romance and status. Editor: And consider the labor that goes into this materiality! Not just Esther Howland, who cleverly structured its production, but the anonymous female workers. Their hours of cutting and assembling represent another layer of social history embedded in the object itself. Did they think about love, as they pasted? Curator: It speaks to a time when personal and economic spheres were even more intertwined. Think about it. These weren't simply commodities; they were vehicles through which a network of social relations was built, a complex circulation of affection. Editor: Absolutely. Beyond the sweetness and sentimentality of this "Valentine" we see a testament to craft, industrial innovation, and the socio-economic forces that shaped 19th-century culture. Curator: Ultimately, “Valentine” allows us a unique entry point into the cultural practices and values of a bygone era. A tangible artifact representing larger systems. Editor: I agree. It encourages us to look closer and appreciate the skilled hands that produced it as well as reflect upon the culture of labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.