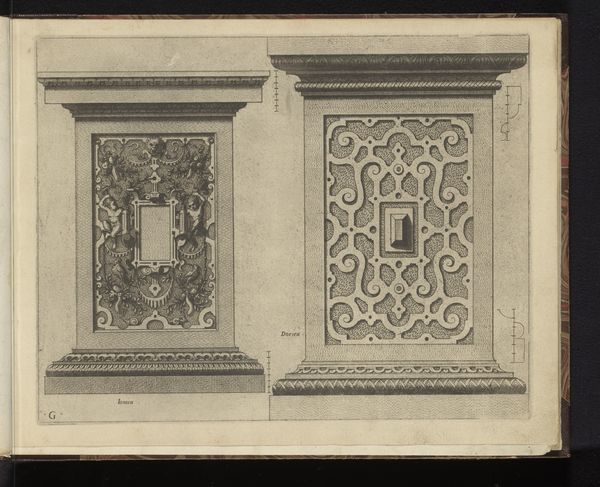

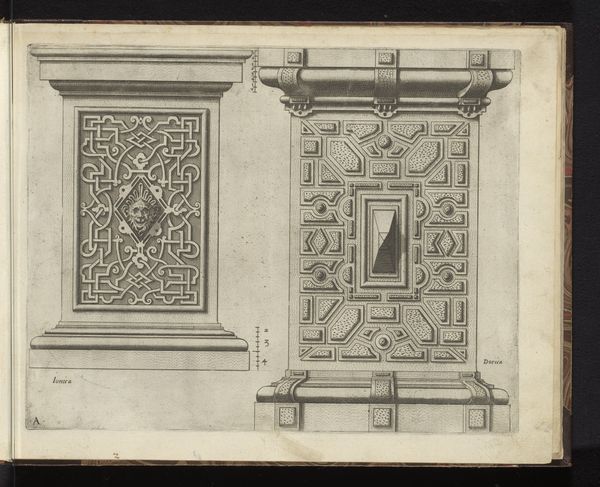

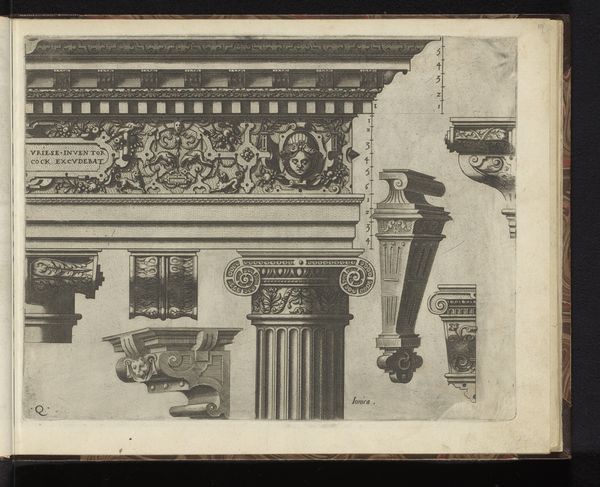

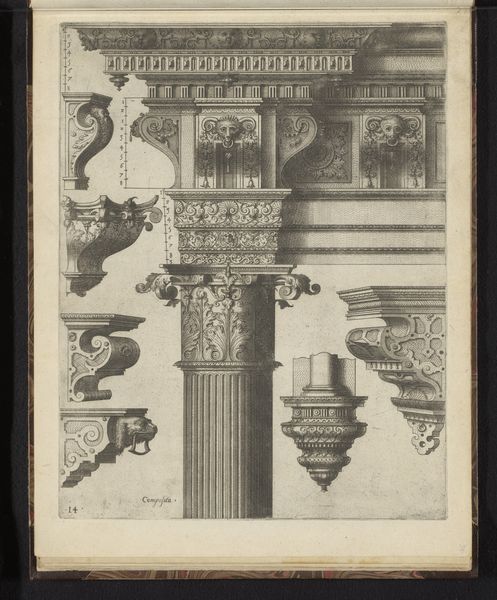

drawing, print, paper, pen, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

paper

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

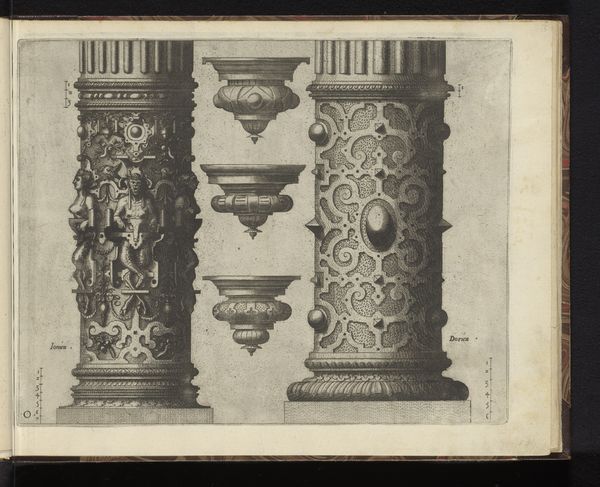

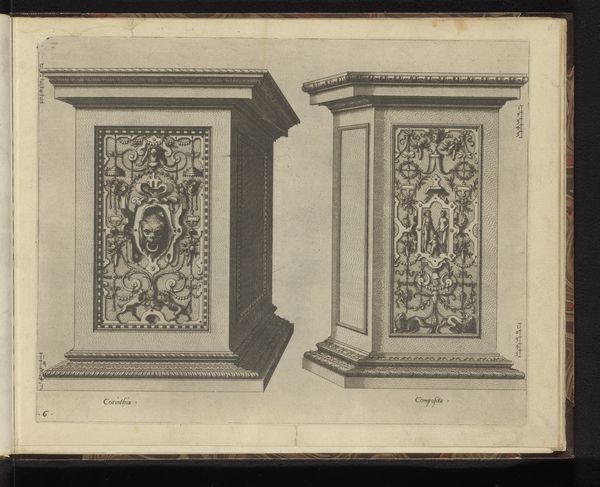

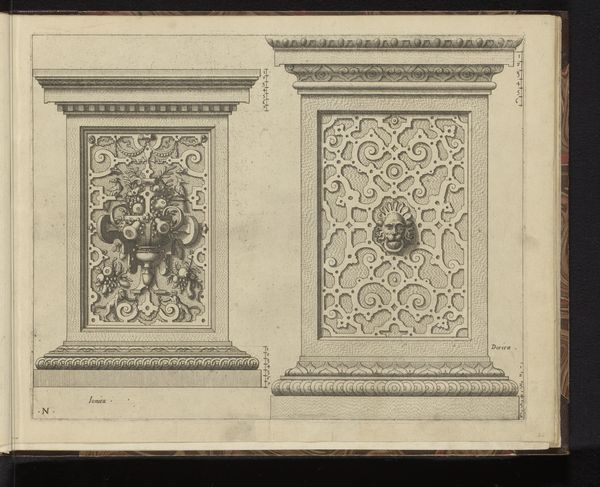

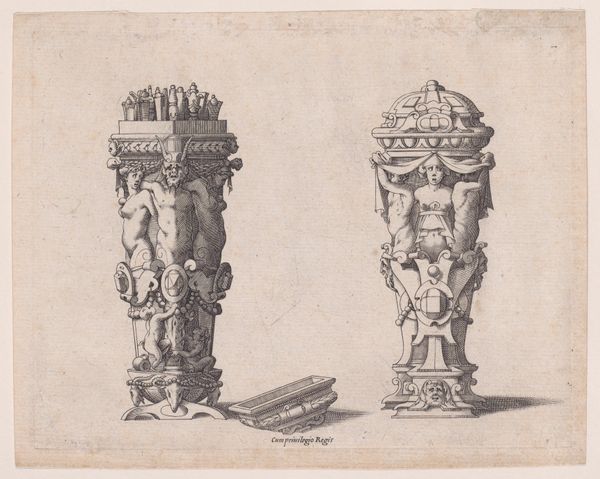

column

#

pen and pencil

#

line

#

pen

#

engraving

#

architecture

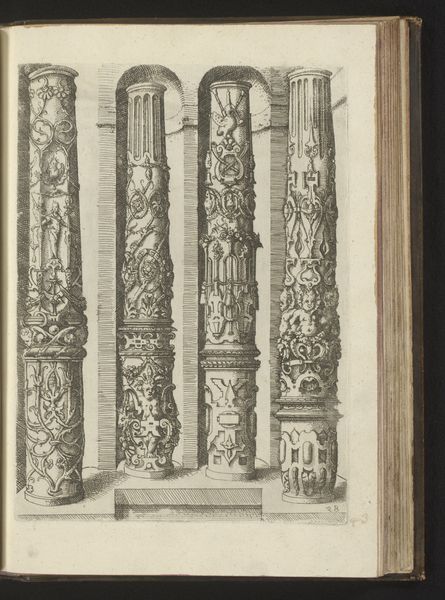

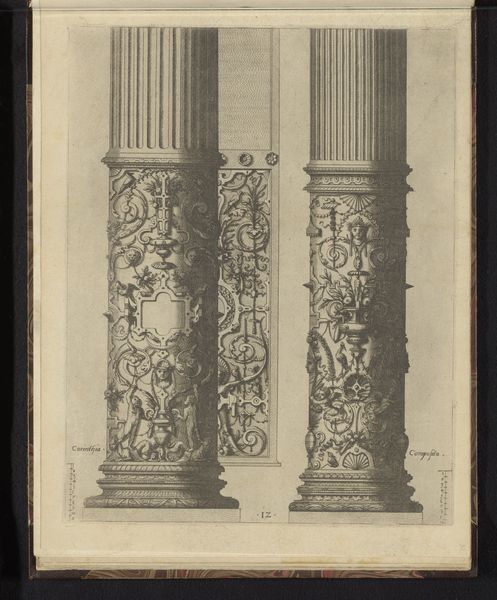

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 301 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Twee 'columnae caelatae'," from 1565, by Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum, a print on paper. I'm immediately struck by the contrast between the intricate detailing of the columns and the relative simplicity of the printed medium. What do you see in this piece? Curator: The image reveals a great deal about 16th-century modes of artistic production and consumption. Consider the engraving itself: it’s a repeatable image, made possible through skilled labor and the application of specific materials - inks, paper, the engraving tools themselves. These allowed for wide distribution and accessibility. We must consider who commissioned this print and for what purpose. Was it a design template for artisans, or a status symbol of knowledge acquired through such designs? Editor: That’s fascinating! It almost feels like a predecessor to a modern-day catalogue. But the focus on design—would this have been considered “art” in its time, or something else entirely? Curator: The line between “high art” and “craft” was far more fluid then. Engravings like this blurred that boundary. The materials – the pen, ink, and paper – become tools not just for artistic expression, but also for the dissemination of knowledge and, potentially, for social climbing. Did the widespread availability of such prints democratize design, or did it merely reinforce existing hierarchies through access to luxury aesthetics? Editor: So, by understanding the process and the materials, we start to unpack its social significance. It challenges this idea of the artist as some lone genius, right? Curator: Precisely. The artist’s individual hand is only part of the equation. Consider the paper, the ink, the printing press. All contribute to the final product, reflecting broader economic and social conditions. This object allows us to reflect on the intersection of skill, labor, and commodity culture in the Renaissance. Editor: I never thought about it that way before. Thanks for helping me look beyond just the image itself! Curator: It is essential that we do look beyond. Focusing on the material and the making brings us closer to understanding the object's multifaceted story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.