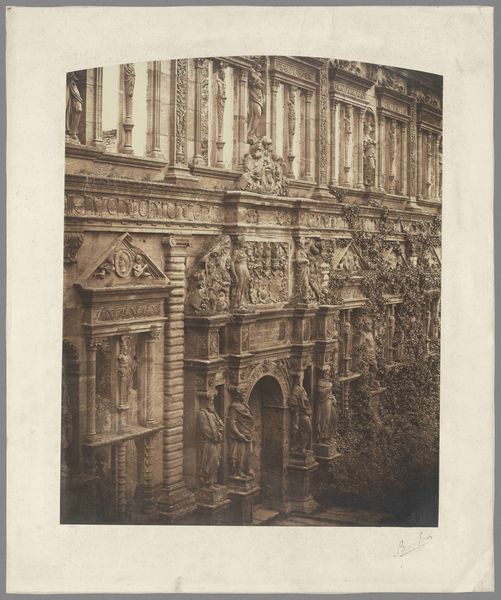

tempera, print, photography, architecture

#

tempera

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

italian-renaissance

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 380 mm, width 287 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

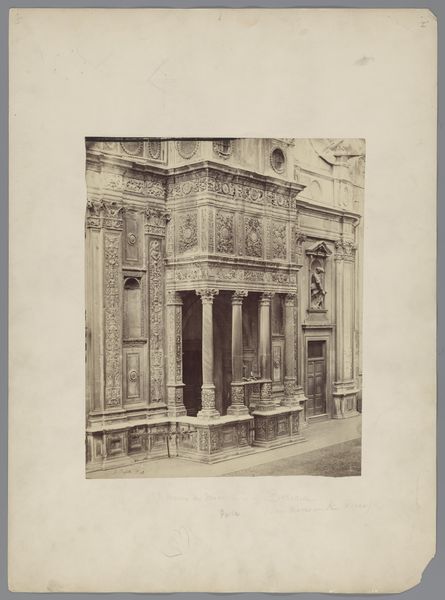

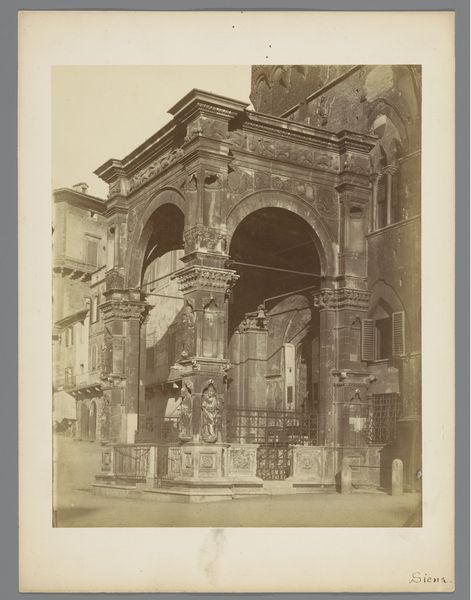

Editor: So, this is Alfredo Noack's "Hoofdingang van de Certosa di Pavia," created before 1882. It looks like a photograph of the monastery’s facade, almost sepia-toned. All the ornamentation feels incredibly dense and...expensive. What can you tell me about this image? Curator: Let's think about this photograph not just as a record, but as a *thing*. Noack, a commercial photographer, chose photography to reproduce architecture. He created prints, commodities affordable to tourists during the 19th century. Note how the light interacts with the facade, creating sharp definition. This shows mastery over process and material--the photographic chemicals and paper. Editor: So you’re saying its significance lies less in its artistic expression, and more in how it reveals 19th-century industry and commerce? Curator: Exactly. Consider the labor involved: from quarrying the stone, carving those sculptures, constructing the building over generations and now documenting and distributing prints, not for artistic reasons, but as a way to cater to burgeoning tourism. Can we then isolate the building’s facade from its history of making and the subsequent commodification? Editor: I see your point. We’re meant to think about the process, from the initial quarrying to the sale of prints. Something that may seem like just documenting history is really highlighting a much broader social picture. Curator: And consider the consumption this image encourages. People want a piece of Italian Renaissance splendor; the print provides just that at an affordable price, blurring lines between "high art" and accessible product. Editor: That's such a fascinating perspective, looking past the artistic value and more towards the materiality and socio-economic aspect! It makes you consider so many different layers. Curator: Absolutely! By exploring materiality, we can explore a different realm to understand and interpret history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.