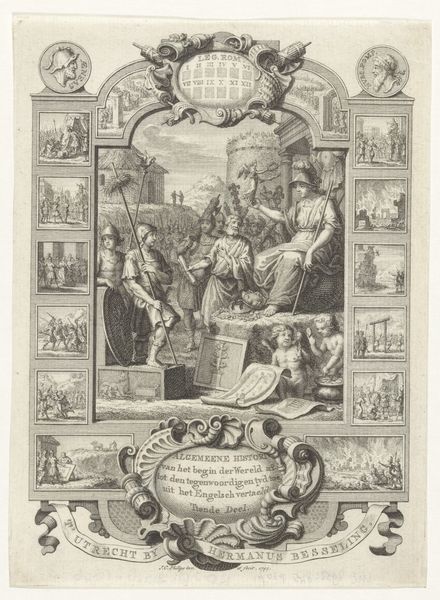

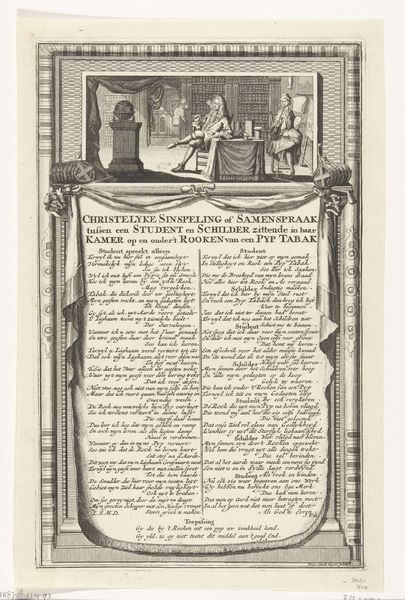

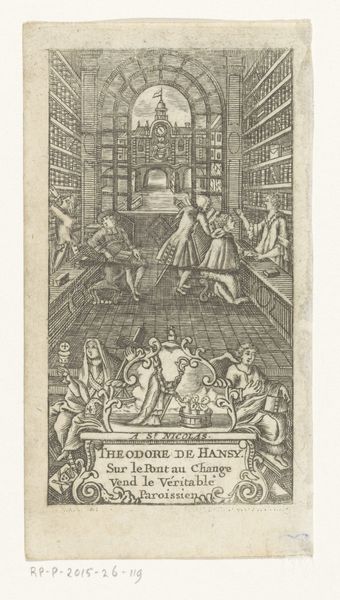

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

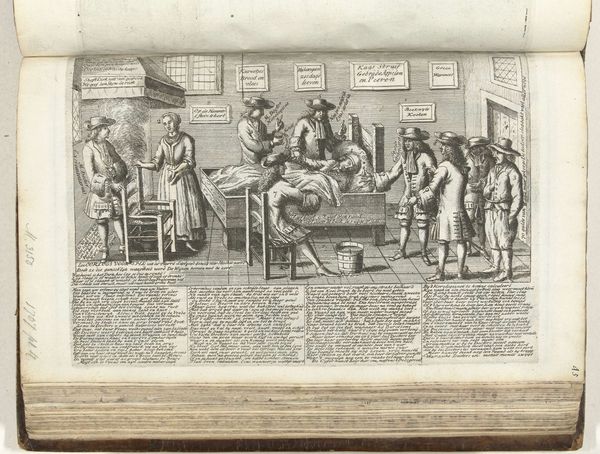

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 141 mm, height 212 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, dating from 1664, is titled "Twee gevangenen aan het werk in het rasphuis," which translates to "Two prisoners working in the rasp house." Editor: My first impression is stark: the bare torsos and focused effort of the prisoners against that barred window suggests relentless, grueling work in a grim atmosphere. Curator: Precisely. The print offers a glimpse into the Rasphuis, one of Amsterdam’s early correctional facilities. These institutions aimed to rehabilitate criminals through hard labor. Here, we see two men, possibly stripped to the waist because of the intensity of labor, using a large rasp to grind a log of brazilwood into powder. This powder was a valuable commodity used for dyeing textiles. Editor: What strikes me is the composition. The central table acts as a focal point, but the heavy chains on their ankles suggest they're confined—a symbol of how the facility hoped to curb and reshape social deviancy through physical labor and routine. The image, rendered in this distinctive line engraving style, is so potent. Curator: Engravings like this weren’t merely documentary. They communicated moral messages. Notice how their postures express diligence despite their imprisonment? This suggests redemption is achievable through hard work, echoing a prevalent cultural sentiment of the era. They are, ostensibly, paying their debt to society. Editor: Yes, and this piece subtly implies labor's redemptive power. But doesn't it also speak to broader societal issues like poverty, crime, and punishment during the Dutch Golden Age? Prisons like these were designed not just for retribution but also to make inmates economically productive. It raises questions about who profited from this system. Curator: Absolutely. And we should not underestimate the power of symbolism here. Even the choice of brazilwood—a luxury good—being processed by prisoners underlines the complex economic and moral framework underpinning 17th-century Dutch society. Editor: Seeing their focused work humanizes these figures somewhat. We are drawn into their arduous existence, recognizing how incarceration, labor, and resources formed interlocking structures that reproduced power in a society rapidly expanding in wealth and global influence. Curator: This close looking makes one reconsider the engraving less as historical artifact and more as a statement about work. It challenges viewers, across centuries, to ask essential questions regarding labor, and to meditate on the many forms that imprisonment assumes. Editor: Indeed. Reflecting on this artwork compels one to interrogate what truly defines rehabilitation and consider if punitive measures like hard labor are ever actually transformative, or simply perpetuations of power imbalances.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.