albumen-print, photography, albumen-print

#

albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

united-states

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

albumen-print

#

realism

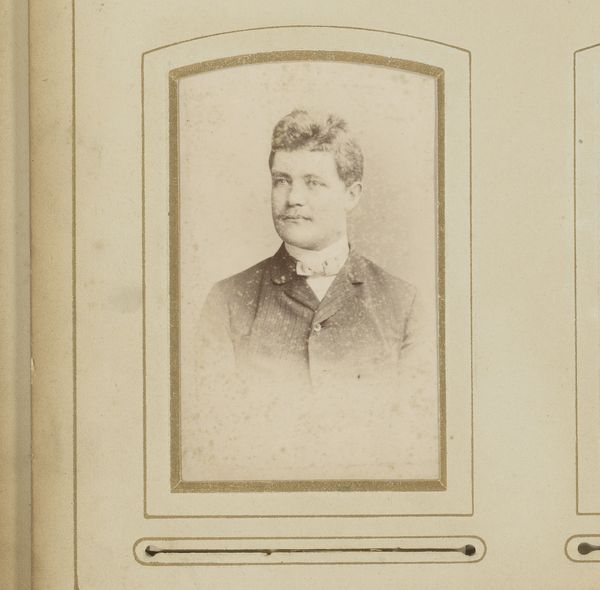

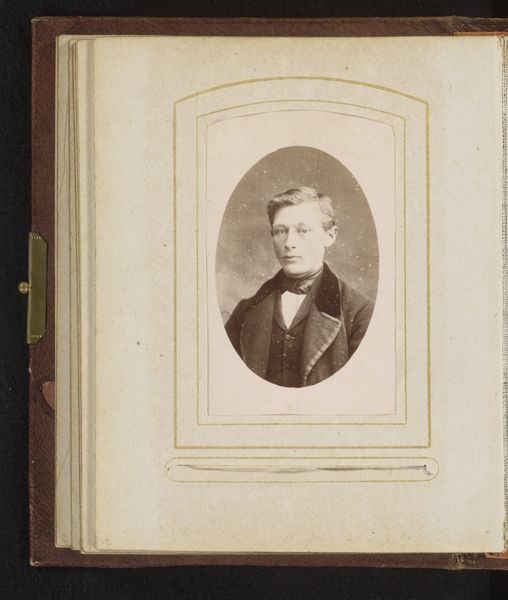

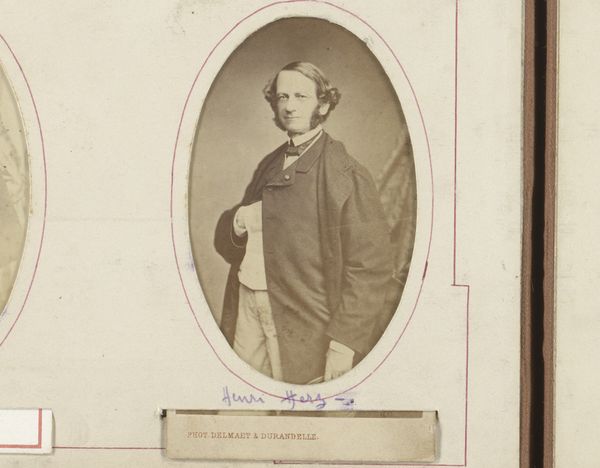

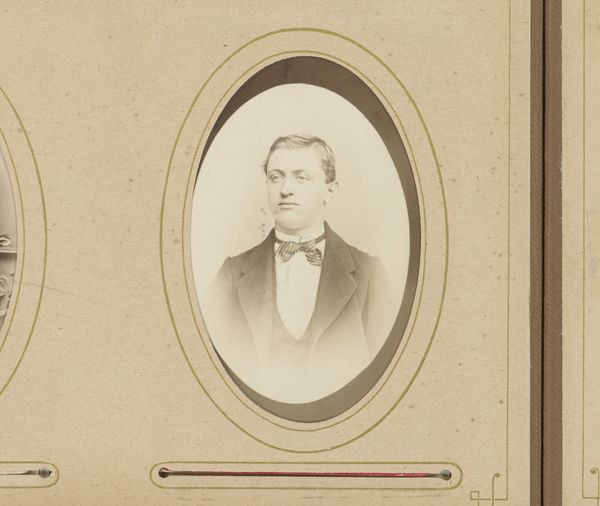

Dimensions: 2 3/4 x 2 1/8 in. (6.99 x 5.4 cm) (image)5 3/4 x 4 3/4 in. (14.61 x 12.07 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an albumen print from 1862, a portrait of Thomas March Clark by Jeremiah Gurney. The oval shape and sepia tones give it a sense of age, almost like a memento mori. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: I’m drawn to how portraiture, especially photographic portraiture, became a crucial way of constructing and preserving social memory in the 19th century. Clark's gaze, his clerical collar—they all point to a very specific kind of authority and virtue that the image is trying to convey. What do you think about the way Gurney has framed him, literally, within that oval? Editor: It almost feels like he’s being presented as an ideal, something enclosed and precious. Curator: Precisely. Consider the religious symbolism that might have been important to viewers at the time. While subtle, the framing and composition elevate Clark to a figure of almost iconic status. Does the use of photography, as opposed to painting, impact how you interpret this? Editor: It adds to the sense of realism. A photograph claims to capture a moment, to give us an unvarnished truth. But now that I think about it, that might be deceptive, because of how deliberately the photo is posed and staged. Curator: You're right. Photography, even then, wasn't simply a mirror to reality. It was carefully constructed, imbued with meaning. It's a reminder that all images carry cultural and ideological weight. What’s your biggest takeaway? Editor: That even seemingly straightforward images can be powerful carriers of cultural values, shaped by both the sitter and the photographer. Curator: Indeed. The act of remembering and idealizing is embedded within it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.