painting, plein-air, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

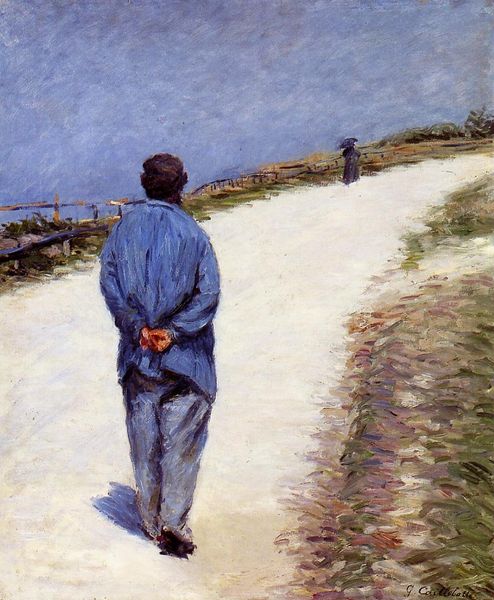

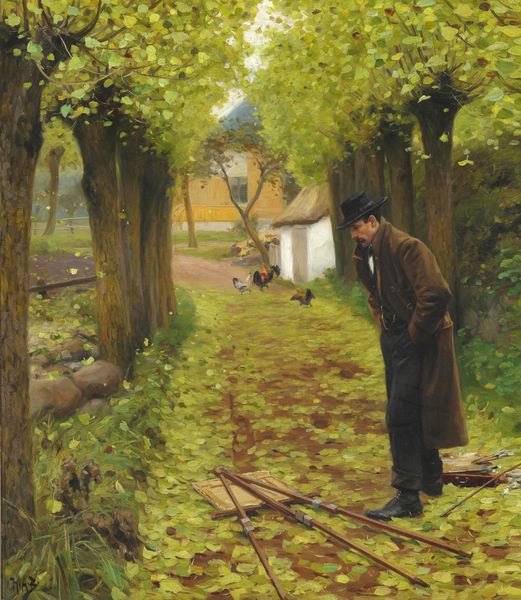

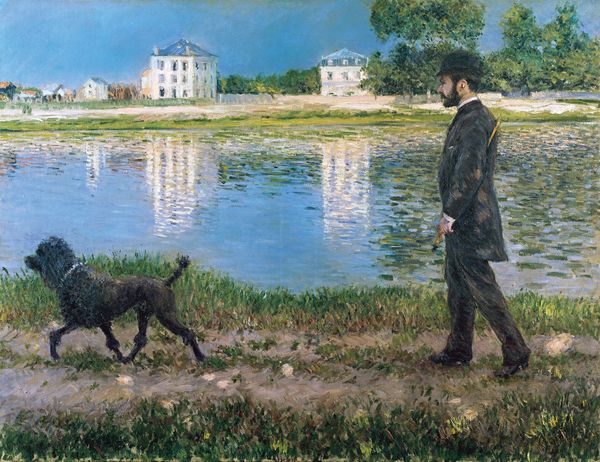

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the light, almost mournful quality of "By the Sea" painted by Gustave Caillebotte around 1885. There is an interesting treatment of atmosphere with the landscape receding into this silvery haze that just softens the edges of everything. Editor: That grey tonality you pick up on definitely dominates the overall mood of the piece, creating a somber feeling that might reflect the class anxieties and societal shifts of that period. The very fact that the figure is represented outdoors invites considerations around plein air as a genre in relationship to shifts in how Parisians consume their leisure time. Curator: Exactly! You see Caillebotte engaging in an established Impressionist method with this en-plain air technique while also grappling with new painting technologies—pre-mixed paints allowing greater flexibility and portability than traditional studio practice, and mass-produced canvases that expand the marketplace and lower the stakes for each composition. Editor: Interesting to consider the impact that technological development had on genre choices as well. Because you're right to bring up portability: that freedom directly impacts Caillebotte's capacity to leave behind the traditional confines of interior space, where domestic portraiture had typically centered bourgeois experience, to really explore how masculinity gets performed out in more fluid public spaces. I mean, the way he's so buttoned up, even strolling through this idyllic landscape, feels very much tied to performance. Curator: Absolutely! The cane, the impeccable suit...these are conscious displays. We know Caillebotte came from wealth, he had the financial means to pursue art, and I think there’s an awareness of that labor in constructing an image that merges established impressionist landscapes and something akin to upper-middle class portraiture. The painting itself becomes a material signifier of that privileged mobility, made possible through mass manufacturing processes in this period. Editor: So, reading the composition as less concerned with simply representing a scene, and instead viewing it as evidence of these tensions emerging with the newly configured social landscapes? The lone bourgeois male negotiating both leisure time and public space? Curator: Precisely. And while the painting's quiet beauty is undeniable, examining the conditions of its production—from paint tubes to patronage networks—offers insight into the social world it inhabited, which allows for a much deeper understanding, I think, of both the aesthetic choices at play and what Caillebotte wanted to show us. Editor: It's certainly a compelling reading, giving insight into how shifting economic factors really reshaped this historical narrative around representations of bourgeois subjects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.