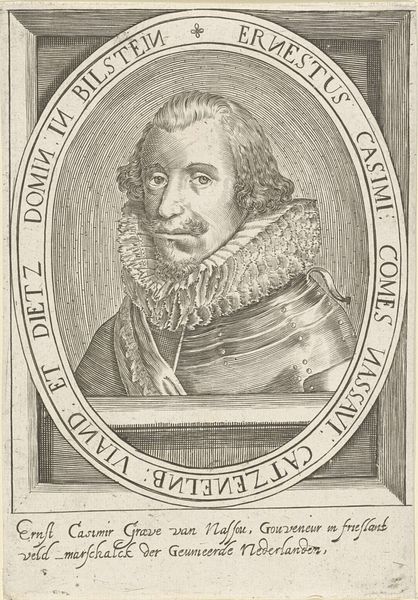

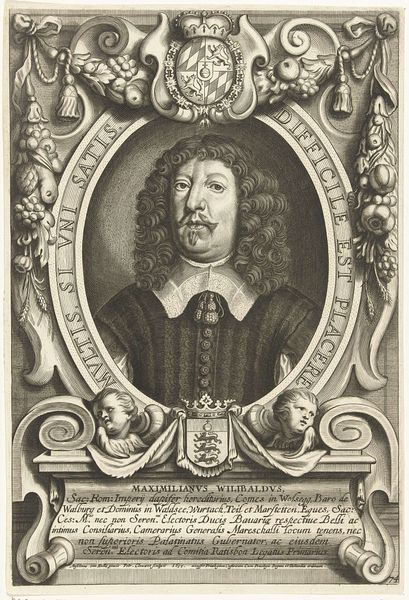

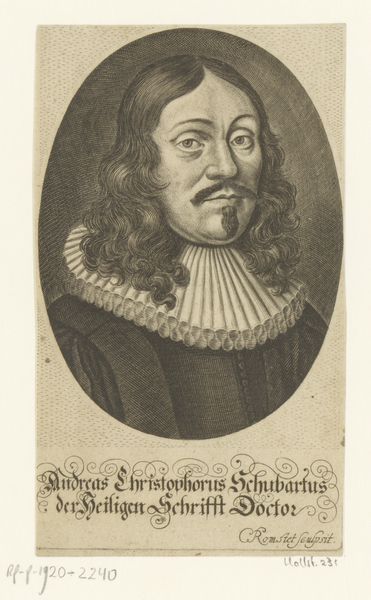

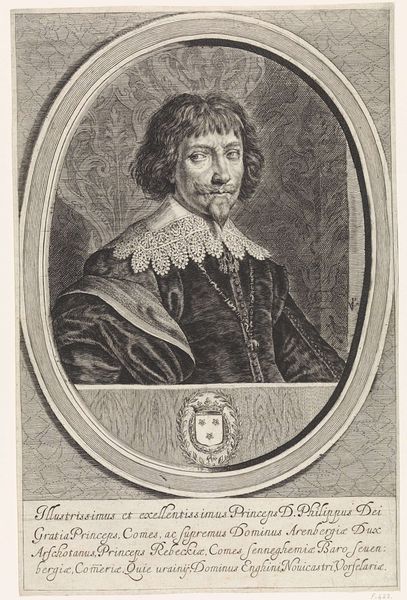

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

personal sketchbook

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 183 mm, width 131 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print titled "Portret van Lodewijk XIII," or "Portrait of Louis XIII," made sometime between 1604 and 1670 by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me immediately as meticulously rendered. The lines create an almost tangible texture, giving the piece a surprising sense of depth, despite its obviously limited tonal range. Curator: Well, consider that this is an engraving. It required tremendous skill in metalworking and etching to achieve this level of detail. The artist would have used various tools to carve lines into a metal plate, which was then inked and printed. The whole process highlights the labor and craft involved. Think about the communities that sprung up around printmaking—the workshops, the apprenticeships, the trade networks that disseminated these images. Editor: Absolutely, and these prints played a crucial role in shaping public perception, disseminating not just images, but ideas. Think about Louis XIII himself. By commissioning or permitting the circulation of this portrait, he's controlling his image, projecting power and authority, especially within the context of the tumultuous religious and political landscape of 17th century France. The Baroque style, too, contributes to this projection—the ornamentation and the dramatic composition all serve to amplify his status. Curator: And the text surrounding the portrait, framing it in a way. It is quite telling: “Virtuti damnoia Quies,” loosely translated to "Virtue knows no rest," speaks directly to the expectation that the ruler serves with never-ending, ceaseless dedication, to his country, people, and religious duty. The use of Latin adds a layer of learned sophistication intended to be understood, likely, only to a select learned, elite few. Editor: Right, and that selective access, that intended audience, reinforces existing power dynamics. The visual language works in concert with social structures, bolstering existing systems of privilege. It encourages questions about how these kinds of portraits impacted the lives of everyday people who never saw the king in person. Did these images foster a sense of national unity or deepen existing social divides? Curator: These objects, and any like it, exist as powerful commodities. It is fascinating to consider that prints like this one, intended for wide dissemination, were integral to constructing the monarchy’s narrative, cementing its cultural legacy for a nation in search of itself, so to speak. Editor: Precisely. Looking at this piece, one can't help but ponder the stories it both tells and obscures. What power dynamics are at play? Curator: Exactly! This is an exceptional illustration of material practices, informing how images construct narratives. Editor: Leaving me to consider it in context as a potent intersection between art, history, and social power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.