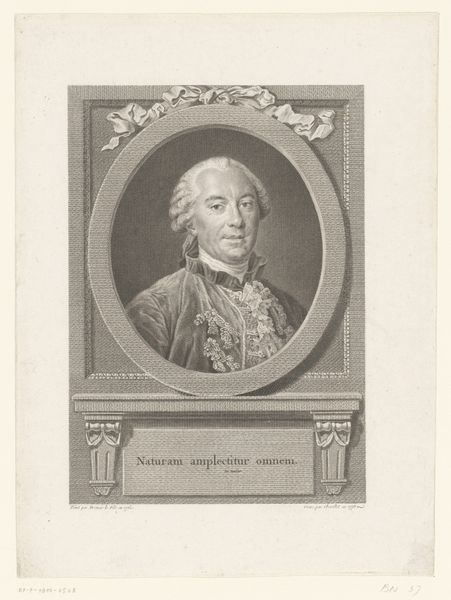

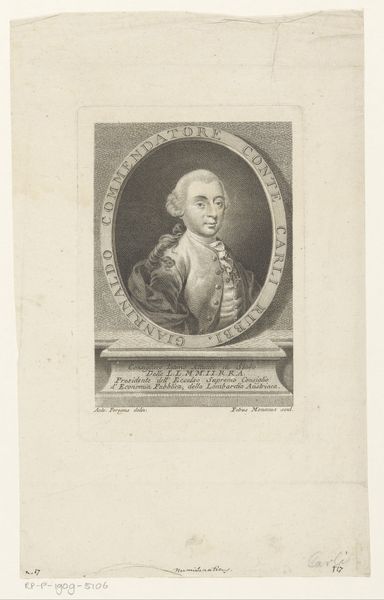

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 274 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a work called "Portret van Charles Henri Hector d'Estaing," an engraving by Charles Etienne Gaucher from 1779. The precision and detail achieved with engraving are striking. What aspects of this piece grab your attention? Curator: Well, looking at the engraving itself, I see a convergence of labor, materiality, and social context. We have an image of aristocracy rendered through a very deliberate process of incising lines into a metal plate, a labor-intensive method. Editor: So you're saying the choice of engraving isn't just aesthetic? Curator: Precisely. Consider the historical context: engravings like this were a means of disseminating images and ideas, acting as a sort of early mass media. The very act of creating and distributing this portrait, a commodity, speaks to power dynamics. How many engravings would Gaucher have needed to sell, and to whom, to make ends meet? Editor: I hadn’t considered the economics of it. So, you're saying the *how* and *why* it was made is more significant than just who it depicts? Curator: The “who” is certainly connected. D'Estaing’s status fueled demand for images of him, driving production. This highlights a fascinating relationship between aristocratic patronage, artisan labor, and burgeoning consumer culture. Where did the copper come from to create the plate in the first place? What tools were involved? All those considerations open doors to understanding society at the time. Editor: I see it now – thinking about the materials and process tells us about power structures, class, and even global trade. Thank you, that really changes how I look at engravings now. Curator: Absolutely. By looking beyond the surface, the materiality of the art provides deep social insight.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.