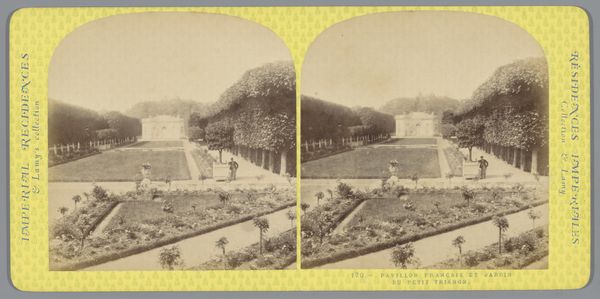

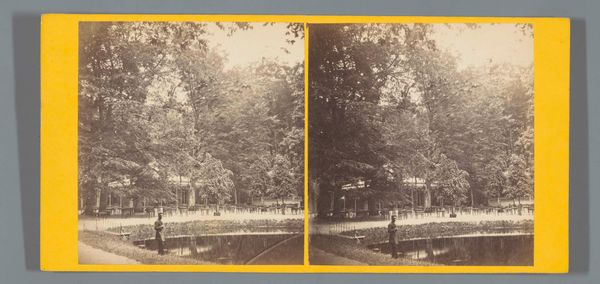

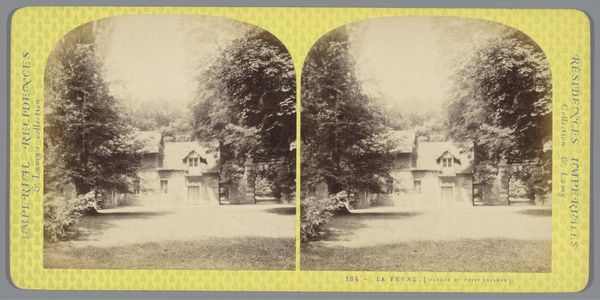

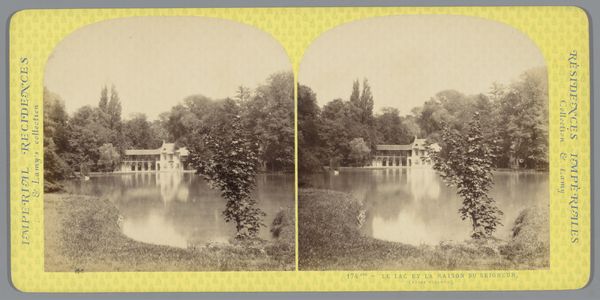

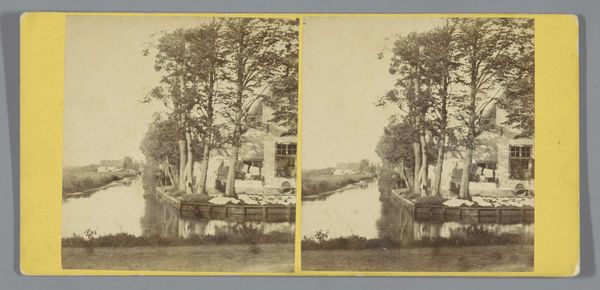

Gezicht op het meer en de molen in Le Hameau de la Reine bij het Petit Trianon 1860 - 1880

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a stereoscopic albumen print from between 1860 and 1880 by Ernest Eléonor Pierre Lamy, titled "View of the lake and the mill in Le Hameau de la Reine near the Petit Trianon". Editor: There's something so serene about it. The stillness of the water, the symmetry, it feels almost staged, doesn't it? Curator: The "staging" is quite literal here. Marie Antoinette commissioned Le Hameau de la Reine, the Queen's Hamlet, as a retreat from courtly life. These manufactured rural settings were designed for leisurely pursuits and allowed aristocrats to play at being farmers. Lamy's photographs, reproduced via albumen printing, capture and arguably participate in the circulation of such fantasies, allowing for vicarious consumption by the masses. Editor: So this image isn't just a picturesque landscape. The very act of producing and then consuming it becomes a way of validating certain class distinctions, right? The industrial reproduction and distribution of these idyllic fantasies helped justify a social order predicated on unequal access to land and resources. But what about the technique? Curator: The albumen print process was widespread and significant. It used egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper, creating a glossy surface. In a capitalist society, it turned images into a consumable object, allowing them to reach a mass market beyond the elites initially involved with commissioning such scenes. It's an industrial approach that rendered aristocratic pastimes into mass consumption. Editor: And Lamy here, as the photographer and therefore the creator, facilitated that democratization through craft... it’s almost ironic given the subject matter. By mass producing these photographs through labor intensive, alchemic-like, printing methods, it blurs boundaries between high art, reportage, and accessible commercial product. Curator: Precisely. And thinking about the afterlife of this image in our own context highlights the tension inherent in collecting and exhibiting such works, a reflection of historical social stratifications now displayed, critiqued, or simply viewed. Editor: True. Seeing this, knowing what it depicts and how it was disseminated in the 19th century and now experiencing it as a recontextualized artifact, shifts the meaning further and further away from its initial conception. Curator: Ultimately it leaves me pondering the ever-shifting nature of an image's legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.