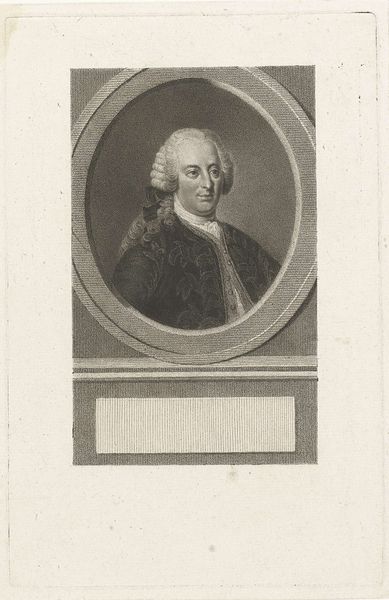

Dimensions: height 157 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Philippus Velijn's "Portret van Onno Zwier van Haren," an engraving that the Rijksmuseum dates between 1797 and 1836. It has a very formal, almost stately feeling to it. How do you interpret this work? Curator: This portrait, like many of its time, operates on multiple levels. On one level, it is clearly an image of status. But it also raises questions about representation and power. What does it mean to present oneself in this way? Who has the power to commission and disseminate such images, and whose stories are excluded as a result? How might period concepts of class, privilege and cultural hierarchies inform his look and pose? Editor: That’s a good point, and how does that relate to our world now? Curator: Consider how similar power dynamics still shape portraiture today. While the technology has evolved, the core issues of representation, self-fashioning, and access remain remarkably relevant. How do we choose to present ourselves online, and who controls those narratives? Editor: So it's not just about historical context; it's about understanding ongoing social dynamics. Does the very choice of the engraving medium factor into how the portrait addresses representation and access? Curator: Precisely! Engravings allowed for wider dissemination than painted portraits, suggesting an attempt to broaden access, at least to a certain segment of society. However, that accessibility was still limited by literacy and socioeconomic status. Thinking about this tension helps us question easy assumptions about democratization of art in any era. Editor: It makes you wonder about the limitations of "access" even when strides are being made. I am going to view this differently now. Curator: Exactly. That's what art can do – provoke critical reflection and offer new perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.