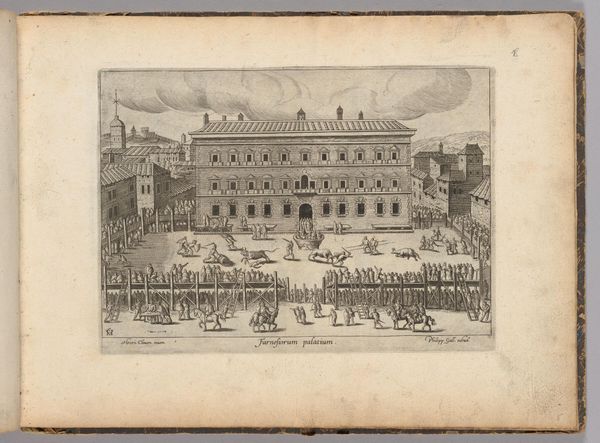

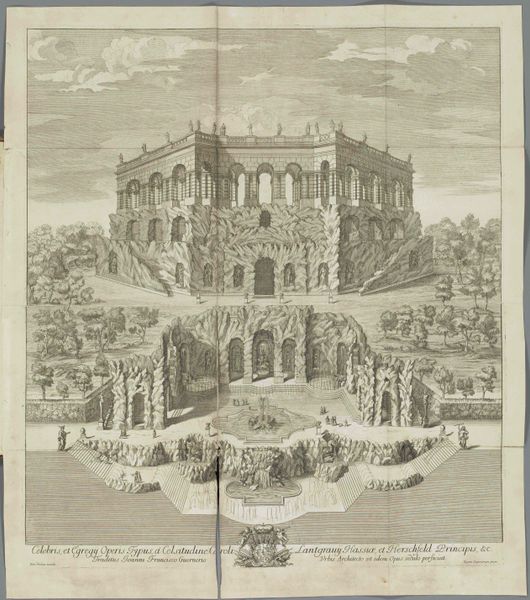

print, etching, watercolor, engraving

#

venetian-painting

#

water colours

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 490 mm, width 590 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "San Marcoplein te Venetië," possibly from between 1675 and 1717, I’m immediately drawn into the print’s depiction of Venice’s political and social stage. What are your initial thoughts on it? Editor: There's a peculiar blend of calmness and implied activity, isn't there? The almost pastel palette creates this dreamlike quality, even with the square bustling with figures. I wonder what visual motifs stand out? Curator: It’s all about the symbols of power here, both civic and religious. Notice the columns topped with the Lion of Saint Mark and a religious figure, flanking the Doge's Palace. Venice's unique governance, that blend of merchantile prowess and Doge rule, is visibly present. The piece places the viewer within a very particular worldview. Editor: Absolutely! And speaking of symbols, consider the recurrent gondolas. More than just transportation, they're almost totemic of Venetian identity. They subtly reiterate Venice’s connection to the water, which is intrinsic to its cultural memory. What purpose might these figures have served in the city at this time? Curator: That is where the question of context becomes pertinent, especially given the artwork is ascribed to Pieter Schenk, as an engraver and printmaker the distribution and social reception of images would be essential to their intended meaning, their value was found not only in art appreciation but information spreading. We see the beginnings of mass media and their influence. Editor: Schenk also includes many individual characters in the square and around the waterways. There appears to be life, transactions, exchanges happening. This almost invites viewers of the work to superimpose their image into the world. What sort of narrative are you encountering as a modern viewer? Curator: It offers a stylized, curated perspective, for sure, but with glimpses of relatable everyday activity. It really underscores how the powerful families wanted to present Venice to both its own citizens and foreign dignitaries. This type of representation cements the ruling class image. Editor: It strikes me that we're really looking at a convergence of idealized imagery and emergent social documentation, all interwoven through visual language. This approach makes me reconsider how even these ostensibly objective landscapes inherently shaped or manipulated the perceived reality. Curator: Precisely. By examining this, the etching, engraving and watercolor as more than pretty landscape work, it allows us to analyze 17th-century modes of power. Editor: And for me, I take away a greater appreciation of visual symbols’ continuing potency. They can quietly mould perceptions over centuries, carrying layers of cultural weight we must actively decipher.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.