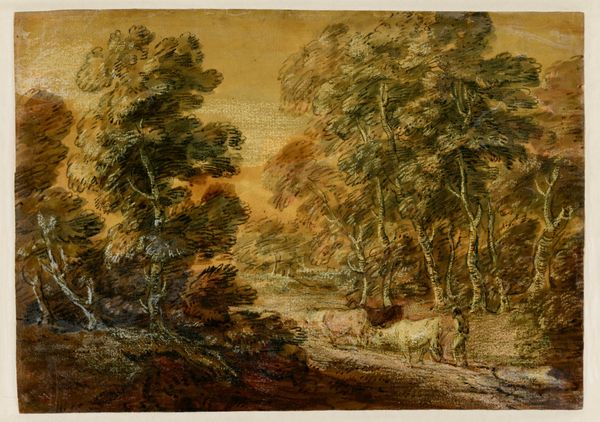

Wooded Landscape with Horseman and Pack Horse c. early 1770s

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 8 1/4 × 11 15/16 in. (21 × 30.32 cm) (image, sheet)16 1/2 x 20 3/8 x 1 7/16 in. (41.91 x 51.75 x 3.59 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Thomas Gainsborough’s "Wooded Landscape with Horseman and Pack Horse" from the early 1770s. It's an ink and watercolor drawing that, to me, evokes a certain sense of longing and transience, especially with that solitary figure. What captures your attention when you look at it? Curator: The Romantics were deeply invested in the power of the individual and their connection to the landscape. Consider the institutions that supported such imagery, largely aristocratic patrons, consuming these picturesque visions of the English countryside. But is it just a simple landscape? Or, perhaps, a veiled comment on social stratification, where even in nature, labor is ever-present? Editor: I see what you mean about the aristocratic connection influencing the style and the reception of the work, since it's almost designed to be consumed as a marker of their status and cultural capital. Does the choice of watercolor and ink, rather than oil, have significance? Curator: Absolutely! The rise of watercolor as a ‘polite’ artform is intertwined with ideas of leisure, portability and national identity. Easy to transport and use outdoors, watercolors became increasingly associated with sketching, a key skill taught within elite social circles. The lightness contrasts sharply with the grandeur often associated with oil paintings, thereby speaking volumes about the cultural and institutional contexts shaping this work. What do you make of the almost theatrical backdrop? Editor: The backdrop adds another layer to that consumption element – framing the scene as a performance for those who can appreciate it, solidifying the social hierarchy within the viewing process itself. Curator: Exactly! This points to how landscape wasn't merely representational; it was performative. It dictated social roles and interactions within those landscapes, shaping and solidifying power structures of that era. I hadn't thought of the theatricality so explicitly. Editor: It's fascinating to see how seemingly simple artistic choices reflect broader social dynamics at play. Thanks for that insight.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Though best known for his magnificent portraits, Thomas Gainsborough preferred painting “landskips” (as he called them) and played a key role in establishing the importance of landscape in British art. As a young artist he enjoyed the beauties of his native Suffolk countryside. After moving to Bath, to pursue the regular income the spa town could provide a portrait painter, he had less time for gamboling through the fields. Instead, he fashioned miniature landscapes, using broccoli for trees, bits of cork or coal for stones, fragments of mirrors for water, and whatever else was to hand. He dedicated an oak folding table to this purpose and would set it up in his parlor. This is not to say he never again drew from nature, but many of his mature landscapes are fantasies deeply informed by experience.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.