painting

#

water colours

#

painting

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

underpainting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 45.7 x 62.2 cm (18 x 24 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

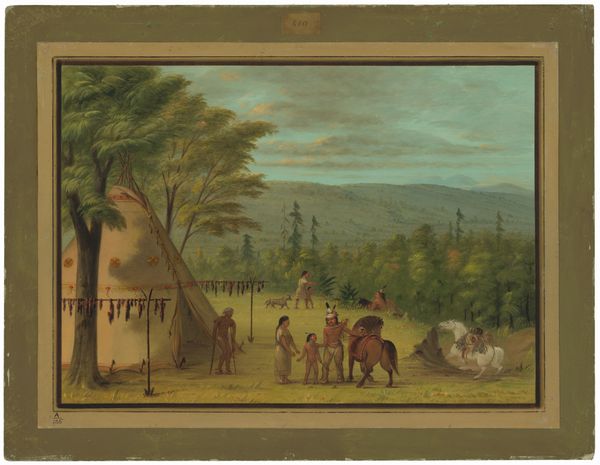

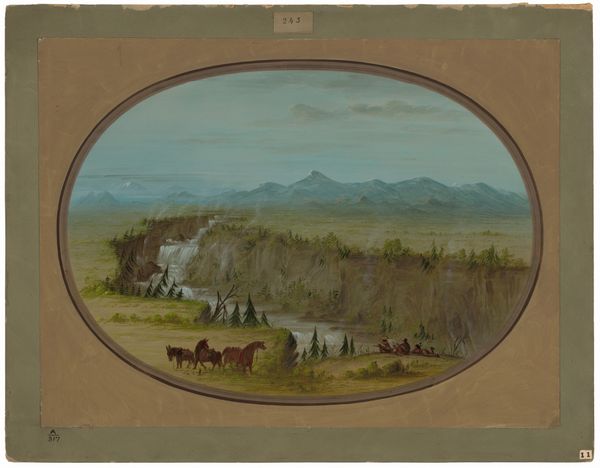

Curator: This watercolor, entitled "A Small Cheyenne Village," was created by George Catlin sometime between 1861 and 1869. Editor: It’s remarkably peaceful. The palette is subdued, with muted greens and tans dominating the composition. There's a sense of tranquility, despite the figures and dwellings populating the scene. Curator: I find the materiality of the watercolor particularly telling. Catlin's choice to work with such a portable, relatively inexpensive medium speaks to his role as a traveling recorder of indigenous cultures. The rapid pace of westward expansion meant capturing these scenes quickly was essential, and watercolor lent itself to that process. Editor: Agreed. The composition itself feels deliberately structured. The foreground establishes the immediate Cheyenne presence through its tepees, and small groups. The sweeping hills draw the eye, while figures scattered across the ridge integrate the landscape into the village life. Curator: We need to consider Catlin's position as an outsider, though. This work is from the period of escalating conflict and forced displacement of indigenous populations, fueled by material interests like land and resources. To what extent does his depiction reflect the true social complexities? What was his own motivation for representation, the distribution and sale of such images? Editor: I see his visual strategy as a careful attempt to portray an integrated community within its landscape. It could, arguably, be an idyllic visual rhetoric—a means of promoting peace, with a focus on capturing a sense of unified people. Curator: Maybe. However, the market Catlin aimed to serve—wealthy patrons, those in positions of political influence—undoubtedly held sway over his artistic choices, potentially shaping a biased perspective, consciously or not, for this picture. This needs more interrogation. Editor: That’s fair. I see the value in considering this serene vista through that critical lens, the tensions of colonial presence at the time and its effects in Catlin’s representational strategies. Curator: Ultimately, what remains is a beautiful artifact, a glimpse into a culture at a crucial juncture. However, recognizing its historical and economic context allows for a richer understanding, one beyond mere aesthetic appreciation. Editor: Yes, it reminds us to examine not just what we see, but the conditions under which that vision was formed, and to acknowledge there are stories layered far beyond its aesthetic impression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.