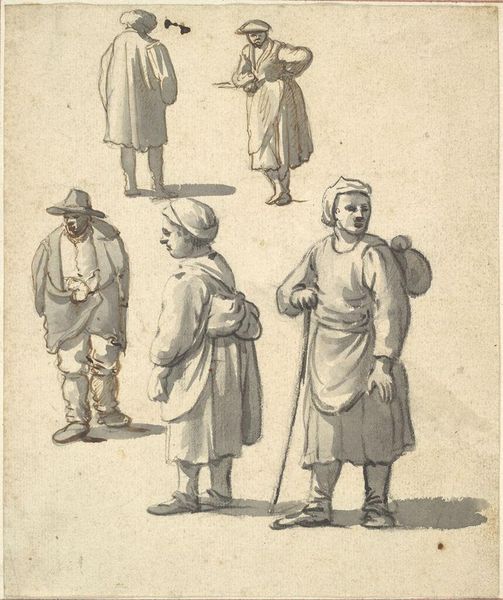

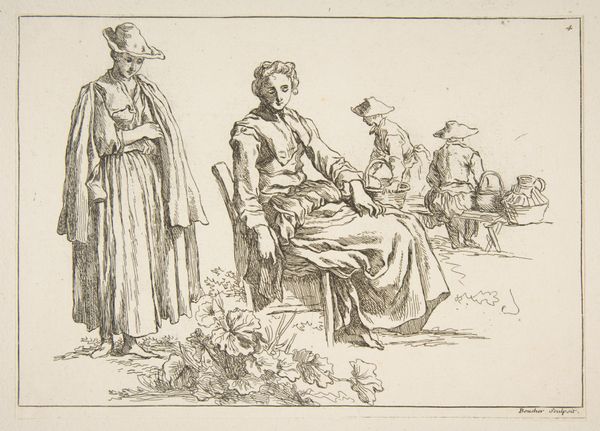

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 185 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: "Boer en boerin," or "Farmer and Wife," a print dating from approximately 1650 to 1700, by Frederick Bloemaert. It is an engraving rendered in a baroque style and currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial impression is of rural simplicity, almost melancholic. The figures seem weighted down, and even the lines feel a bit somber despite it being a genre scene. Curator: That’s perceptive. Bloemaert wasn’t simply depicting peasants; these images functioned within a larger symbolic framework. The basket, the crook, the very presence of the goat – each carries loaded connotations within the cultural lexicon of the time. Editor: Connotations like…what? The goat seems straightforward enough, associated with fertility and perhaps… stubbornness? But are these stock figures in 17th century Dutch art, commenting on rural life? Curator: Yes, certainly the goat carries sexual undertones, but its presence could also speak to rustic abundance and vitality, referencing classical pastoral imagery and themes. As for them being stock figures, that’s where the societal context comes in. Genre painting in that era played a huge role in shaping ideas about nationhood and rural virtue. Editor: So Bloemaert isn’t just drawing farmers; he's constructing an image of an idealised, simple folk, maybe in contrast to urban anxieties? And is that why he focuses on line, simplifying forms to present archetypes rather than individuals? Curator: Precisely. And note the figures aren’t active. There’s a stasis, almost an iconic quality that elevates them beyond simple observation to something more emblematic. Even the line work contributes, it is creating a form, imbuing them with weight. Editor: That static quality is really amplified by their averted gazes, drawing us to speculate more on their significance. Instead of offering insight, the figures and Bloemaert deny a peek in their reality by this averted look. I agree: there's a sense of performance rather than reportage. The goat may suggest vulgarity but in the light of Baroque splendor it also speaks of continuity. Curator: These kinds of pieces really demonstrate how the visual arts functioned within 17th century society, both reflecting and reinforcing the values attributed to certain groups. It shows art can teach cultural memory by shaping beliefs, but sometimes veiling an uncomfortable truth under idealisation. Editor: Indeed, an intriguing piece and fruitful point to examine how the visual narratives can embody layers of psychological and social implications, as valid now as it was 300 years ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.