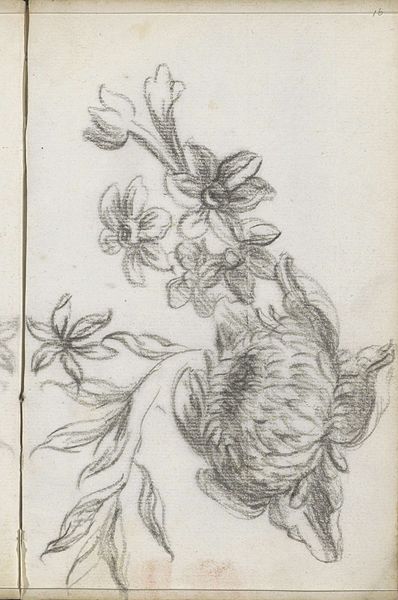

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

organic

#

baroque

#

paper

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

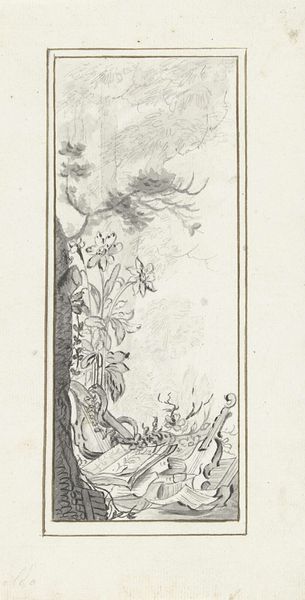

Curator: Looking at "Bloemen," a drawing created between 1710 and 1772 by Petrus Johannes van Reysschoot, the botanical detail is immediately striking. It’s rendered on paper using pencil. What are your initial thoughts on encountering this work? Editor: The immediate feel is quite Baroque, a certain heaviness to the petals even in this simple pencil medium. Almost architectural, how the forms suggest solidity and weight. It is quite serious, but do botanical studies ever truly relax? Curator: Indeed, there is a seriousness—and perhaps that speaks to the broader cultural interest in categorizing and understanding the natural world at the time. The botanical still life, so to speak, becoming more refined in the Western eye. What do you make of its realism? Editor: The "realism," while present, is stylized. The line work is deliberate. Consider the function: was this purely for aesthetic pleasure, or perhaps a study for a larger decorative work? It reflects, I think, the Dutch obsession with detail, especially how Dutch artists were creating a form of conspicuous consumption in paintings of overflowing vessels. Curator: A relevant insight. The Baroque loved a full, overflowing form and certainly, van Reysschoot plays with the organic form of these particular flowers with dramatic flourish, the kind found across the decorative arts during that period. There’s also something interesting in choosing these blossoms. Editor: Exactly. What these flowers might have symbolized, what their trade and social story might have been. Were they especially costly? How did that value become a stand in for general virtues of plenty and grace, which were of interest to aristocratic, educated audiences, or, rather patrons? How are artists always answering the call? Curator: It prompts thinking about how botanical imagery served as not just aesthetic object, but an object of societal fascination—horticulture, global exploration, wealth. And how this image also might function as a kind of “memory object.” I appreciate its delicate lines as it offers a tiny but beautiful perspective onto an important era. Editor: Absolutely. The image, ultimately, reveals so much about our changing relationship to the world—and reminds me that every careful depiction contains worlds beyond its visible surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.