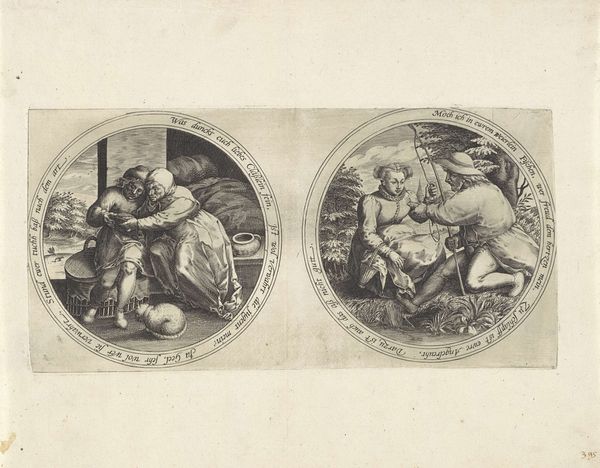

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

mannerism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 153 mm, width 307 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a rather curious print, "Afscheid van een soldaat en man benadert een naaister," created anonymously sometime between 1555 and 1631. It resides in the Rijksmuseum. The piece features two round vignettes, seemingly unrelated at first glance, executed in engraving. What are your immediate impressions? Editor: It feels…awkwardly voyeuristic. The left image seems sorrowful, a farewell. But the right one radiates a rather disturbing lust; it really feels off balance. Curator: Balance is certainly disrupted here. Notice how the iconography in the left panel suggests themes of departure and farewell, while the second depicts an uncomfortable approach and, shall we say, unwanted physical closeness? The visual language is quite stark. Editor: Absolutely, the departure carries symbolic weight. The soldier leaves, perhaps to war, while the image on the right reads like an assertion of male privilege and power at the expense of a woman. There's an implied violation here. Curator: And observe how this print fits within a longer tradition of using genre scenes to illustrate moral narratives. Even these anonymous scenes, with their earthy humor, point toward established allegories. Consider, too, how prints like these acted as forms of portable cultural memory. These visual devices reinforce societal mores through familiar symbolic language, even across time. Editor: But shouldn’t we look critically at those "mores"? Whose morality are we seeing reflected? This piece may uphold traditions of its era, but viewing it through contemporary lenses exposes problematic power dynamics inherent in gender relations. The image evokes so many current conversations about power and gender. Curator: True. And viewing these prints without considering the embedded prejudices and cultural assumptions risks simply perpetuating them, rather than understanding them in context and offering critiques. Editor: This artwork feels particularly relevant because it brings uncomfortable elements of the past into the present moment so that we don’t repeat them unknowingly. Curator: A good observation and useful reminder! It speaks to how we decode not just individual works, but understand enduring and deeply held attitudes, in historical prints. Editor: And, how the language of art—even that embedded in these seemingly straightforward depictions—always whispers of far deeper cultural currents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.