Reproductie naar een foto, schilderij, tekening of prent c. 1860 - 1915

0:00

0:00

diversevervaardigers

Rijksmuseum

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 78 mm, width 163 mm, height 187 mm, width 247 mm, thickness 2 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

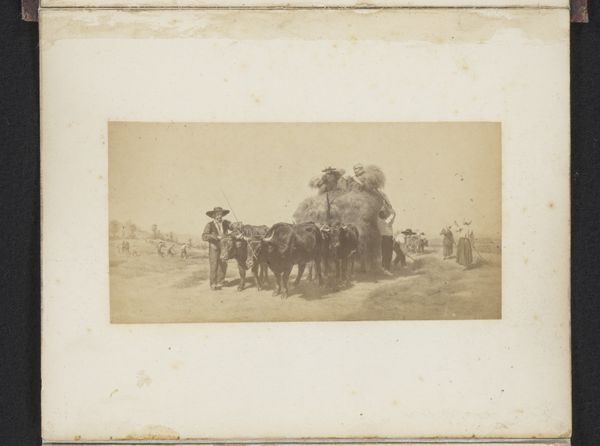

Curator: Let's talk about "Reproductie naar een foto, schilderij, tekening of prent," roughly translated to "Reproduction of a Photograph, Painting, Drawing or Print." It’s attributed to various makers and dates somewhere between 1860 and 1915. It appears to be an albumen print, capturing a cityscape with figures. Editor: There’s an immediate somberness to the work. It's desaturated almost to monochrome and it has a dream-like blur. You get the impression this moment has already disappeared. It looks like it focuses on the working class within an urban landscape. Curator: Precisely! We need to consider the social context of the albumen print. This process was incredibly popular then because it was an easy and relatively inexpensive way to mass-produce photographic images. Think of this not just as art, but also a mass produced consumer product. Editor: Right, its appeal was less about artistic aspiration and more about accessibility. How did its mass production impact our understanding of visual culture? Does the fact that there are many "various makers" reduce our conception of the artist genius mythos? Curator: Absolutely. It forces us to think about the industry and labor involved in image creation during this period. Someone had to prepare the glass plates, coat them with albumen, expose the image, and then print it. What about the consumer of this print, hanging in their parlor? What socio-political statement were they making? Editor: Well, genre painting always brings up interesting issues. It shows everyday life, yet often romanticizes it or injects morals into mundane situations. Does this image document the city or sentimentalize it? And whose sentimentality is privileged, and to what ends? Curator: The subject seems mundane enough. Everyday life as labor, perhaps? A few workers moving material. How do such seemingly objective views, so widely consumed, contribute to shaping cultural understanding of social classes and urbanization in the era? It begs all these questions. Editor: And because of the nature of mass production during the time, one has to wonder how many workers were making images versus other jobs considered the visual arts such as sculpting or easel painting? A reevaluation is due, certainly! Curator: Agreed. Studying pieces such as "Reproductie naar een foto, schilderij, tekening of prent" gives us insight into social hierarchies, urban transformations, and the very economics of visual representation in the 19th century. It serves as a poignant reminder of how deeply intertwined art is with production. Editor: Ultimately, this has really altered my view. I walked in ready to dismiss a small print but left seeing it as a product of the city that it depicts!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.