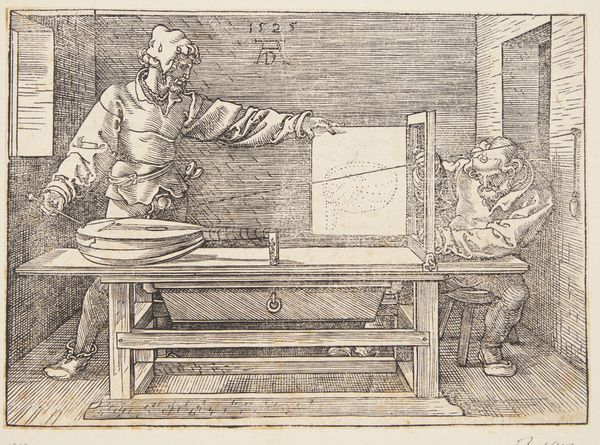

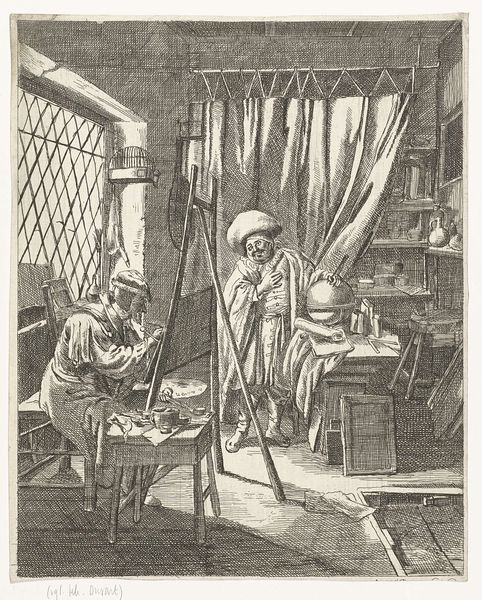

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 167 × 253 mm (image); 175 × 258 mm (plate); 187 × 275 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This print, housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago, is entitled "Portrait of Wenzel Jamnitzer in his Study" by Jost Amman. It was made sometime between 1572 and 1575 using engraving on paper. Editor: Immediately, I'm drawn to the incredible detail Amman achieves with just lines. The textures—the woodgrain of the desk, the fur of Jamnitzer's robes, the light filtering through the leaded glass—it all speaks to the skill and labor involved in its creation. Curator: Absolutely. Jamnitzer, the subject, was a renowned goldsmith, and this image is clearly crafted to elevate his status as a scholar and craftsman, deeply embedding him in the intellectual milieu of the Renaissance. Notice how he’s surrounded by geometric models and tools. Editor: And that speaks directly to Jamnitzer's profession. These aren't just abstract shapes; they are the building blocks for the exquisite metalwork he produced. Think about the hours upon hours required to plan, shape, and decorate. The portrait transforms metalworking from a trade into an art, an intellectual pursuit on par with other "noble" disciplines of the period. Curator: Yes, the very setting reflects the humanistic ideals permeating the 16th century: an active maker and thinker engaged with both theoretical concepts and tangible realities. However, I wonder how much this idealization hides the actual realities of artisan workshops at the time – questions of labor division and the social hierarchies inherent within them. Editor: It's important to note what isn’t shown, absolutely. Who were the people assisting him, and under what conditions? The engraving celebrates craft, yet perhaps obscures the labor processes needed to create it. It’s about what the artwork omits, revealing a hierarchy of the arts. Curator: The gendered implications are apparent, as well. While elite women did participate in the arts as patrons or even artists themselves, this vision of artisanal mastery, with its geometric rigor and learned context, was typically coded as masculine, thus solidifying social power structures within the world of art and craft. Editor: Precisely! What began as a look at the material practice reveals itself as something far broader about how making art intertwines within society's systems of labor, value, gender and even class. Curator: Indeed. Viewing Amman’s print in light of the intricate power dynamics shaping 16th-century society adds invaluable richness to our appreciation. Editor: And for me, it starts from how materials become "art," reminding us that everything we see involves unseen people and processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.