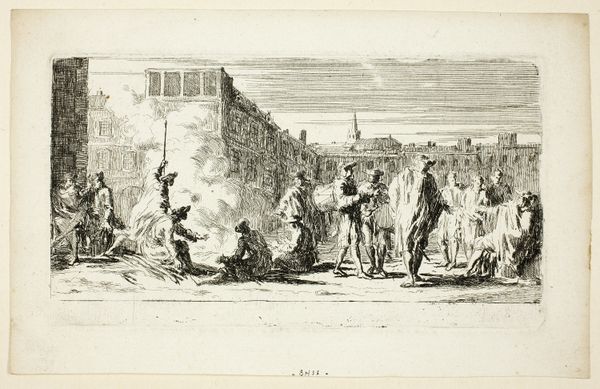

Place du Pantheon, Night of December 22 to 23, 1830 1831

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 175 × 287 mm (image); 221 × 311 mm (primary support); 277 × 390 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

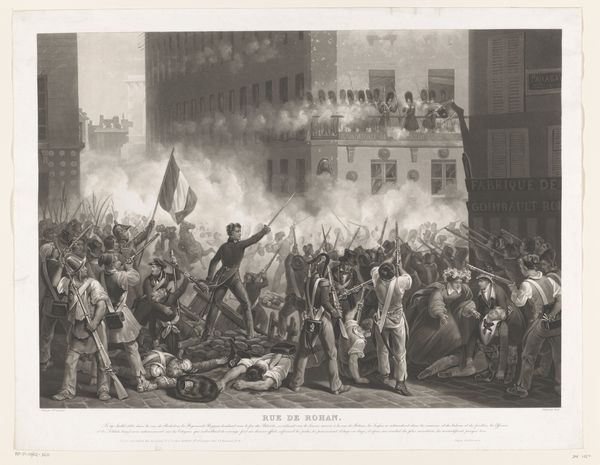

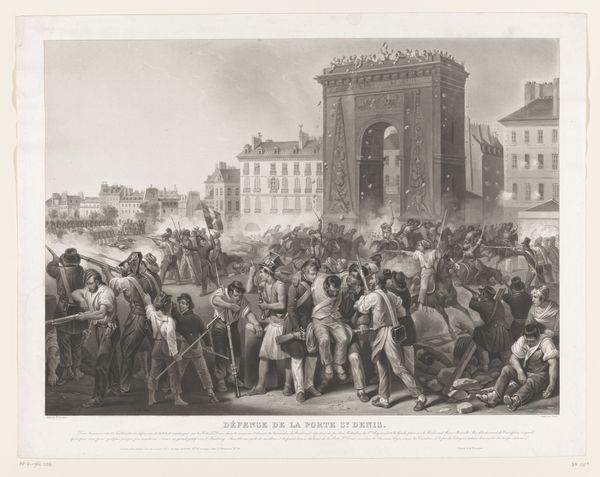

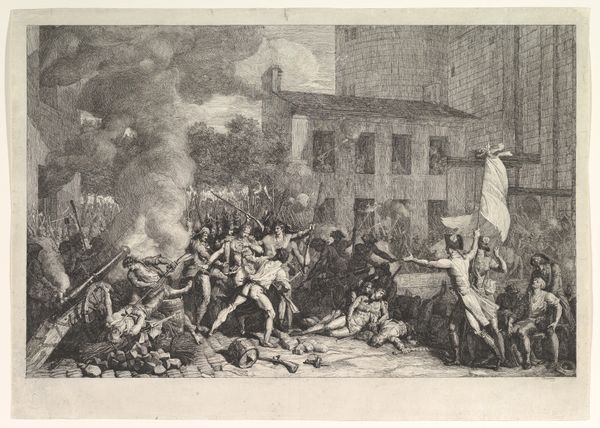

Editor: So, here we have Auguste Raffet’s lithograph from 1831, "Place du Panthéon, Night of December 22 to 23, 1830." It’s a busy cityscape filled with soldiers, and there’s a definite feeling of unease and tension. What do you see going on here, in a historical sense? Curator: This image plunges us right into the heart of the July Revolution's aftermath. Raffet is depicting a very specific moment: the transfer of Voltaire's remains to the Panthéon. But it's more than a simple commemorative scene. The dense crowd, primarily composed of armed soldiers, highlights the fragile state of the new regime. The “people” are represented by military force. Editor: That's fascinating. So, it’s less about celebrating Voltaire and more about projecting power? Curator: Precisely. Consider the Panthéon itself. Originally a church, it was secularized and used to house the remains of prominent French citizens, then re-Christianized, and secularized *again*. Its shifting purpose reflects the turbulent political landscape. What statement is the new regime trying to make by staging this transfer, under such heavy guard? Editor: They’re trying to solidify their legitimacy, using Voltaire, a figure of the Enlightenment, as a symbol of the new order… but needing the military to keep any dissenters in check? The Romantic style adds to that drama. Curator: Yes, and note how Raffet uses the relatively new medium of lithography. Prints like these were easily reproducible, widely circulated, and cheap—allowing the new regime to disseminate this carefully constructed image of power to a broader public. Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. It really makes you think about the control of the message and how easily that image can be spread. It makes a difference seeing a historical event as part of political communication, not just as something that simply happened.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.