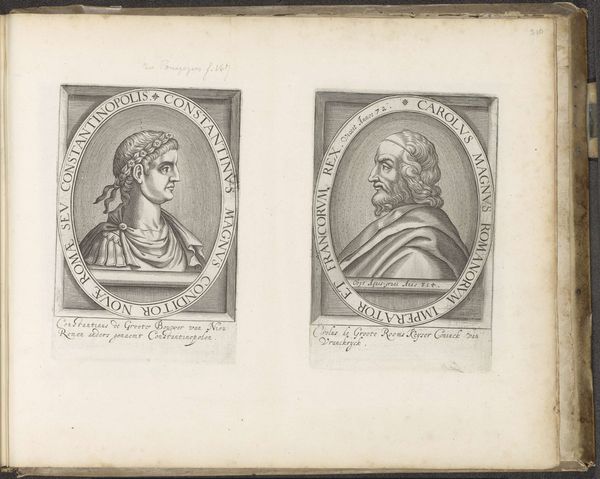

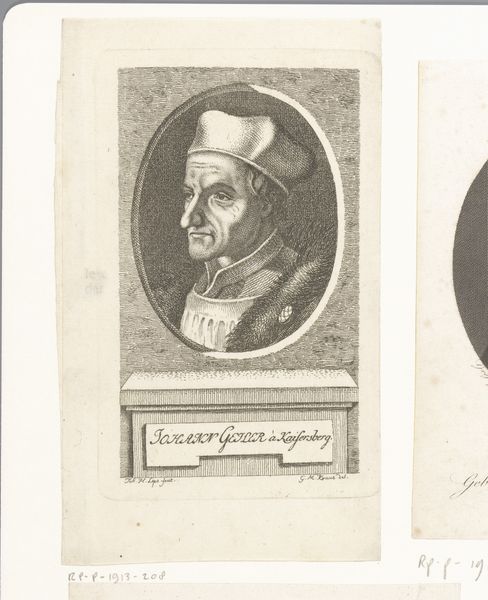

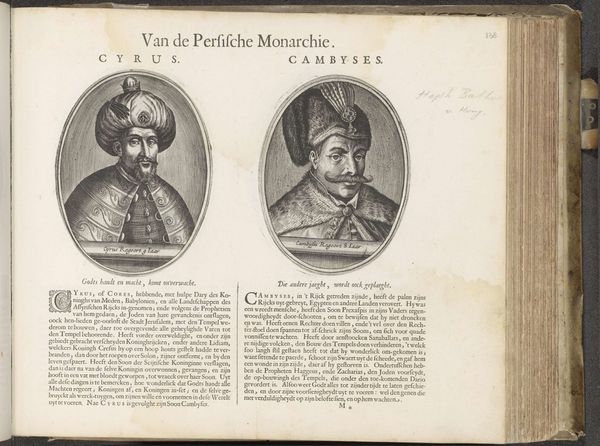

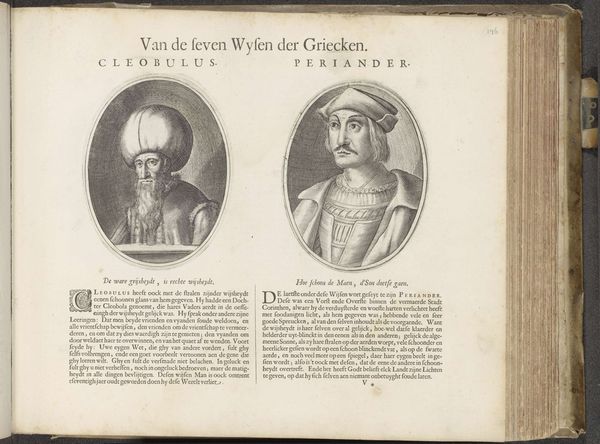

Portretten van de keizers Frederik III en Ferdinand I van Habsburg Possibly 1610 - 1654

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

11_renaissance

#

coloured pencil

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 193 mm, width 126 mm, height 181 mm, width 124 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's look at these "Portretten van de keizers Frederik III en Ferdinand I van Habsburg," two portraits dating probably from 1610 to 1654. The artist remains anonymous. They’re prints held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of rather stern authority. These are clearly men who held power, the lines of their faces and the weight of their garments speak volumes. There’s an interesting starkness, despite the obvious attention to detail in the engraving. Curator: It is fascinating how such images functioned in early modern Europe. Printmaking enabled a wide dissemination of imperial power, influencing both popular and elite perceptions of the Habsburg dynasty. They are carefully posed, surrounded by titles declaring their stature. Consider also what it means for an anonymous printmaker to participate in crafting the imperial image. Editor: Absolutely, and what sociopolitical pressures were at play in image creation? The act of memorializing emperors—which events shaped what was being communicated? How were race, class, and gender implicated? Were these images crafted in response to public demands or dissent? Curator: Precisely. Also, in what ways do portraits bolster political agendas, particularly when circulated broadly. Furthermore, what cultural biases are inadvertently propagated. In effect, portraits become objects whose analysis enables examination into history's silences, questioning assumptions about both ruler and ruled. Editor: Yes, this dialogue opens an insightful channel! I notice too the limitations inherent in printed portraiture, how it reduces these complex men to almost two-dimensional symbolic figures. I feel this is interesting regarding today’s world and contemporary concerns of manufactured versus authentic presentation of selfhood. Curator: This reminds me that representation becomes not just replication but negotiation: understanding its societal consequences remains crucial to unearthing submerged structures and deconstructing any inherent hierarchies, thereby adding considerable depth to portrait interpretation beyond sheer visual aesthetics! Editor: It certainly alters my initial stark impression to imagine the many stories, sociopolitical undercurrents, class stratifications embedded within lines that depict royal representation, each telling an unrecorded dialogue concerning cultural perspectives Curator: Agreed. There's a powerful lesson here about considering not just the visible subject, but also who shaped that image and for what ends. Editor: A profound example that portraits, and specifically prints such as these, act as pivotal objects into social complexities shaping individual perceptions throughout time

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.