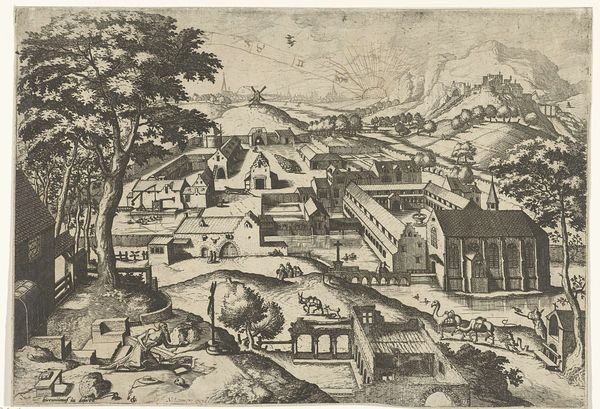

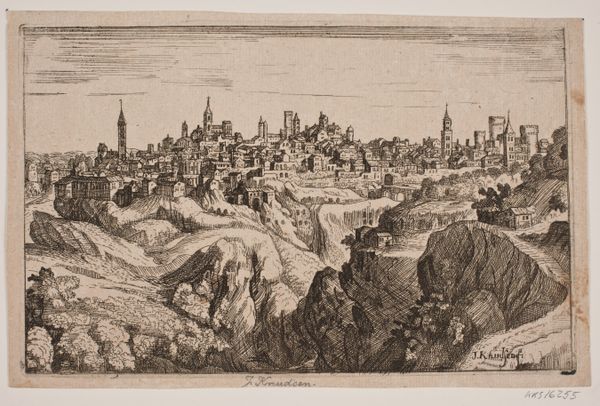

print, engraving

#

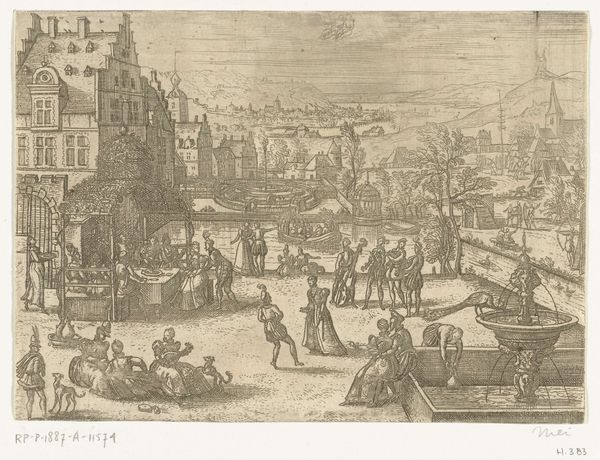

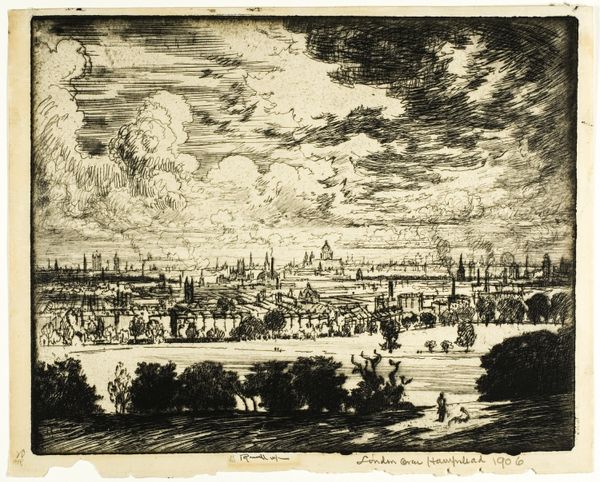

pen drawing

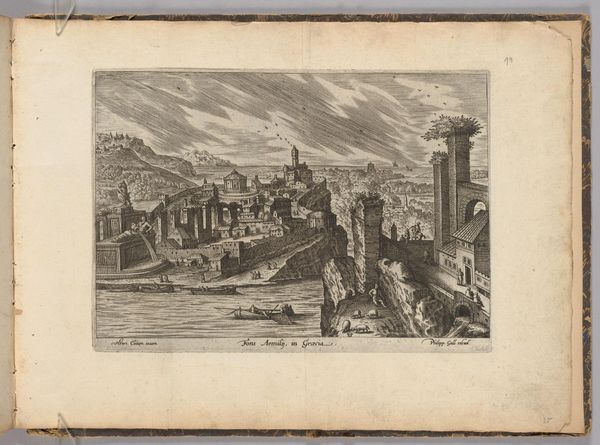

# print

#

landscape

#

mannerism

#

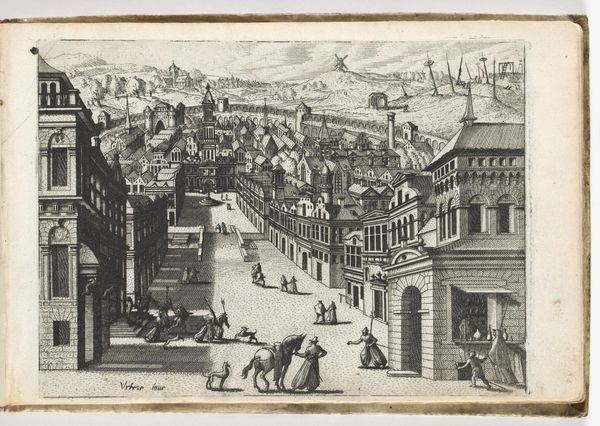

cityscape

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 173 mm, height 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Julius Goltzius brings us "Landschap met een kasteel", dating roughly between 1560 and 1595. The work, held here at the Rijksmuseum, is presented as an engraving, a masterful example of line work. Editor: It's so intricate! Immediately, I'm struck by the detailed execution and the atmosphere; there is almost a feeling of bustling activity amidst a somber landscape. Curator: Indeed. Given Goltzius's Mannerist leanings and the Northern Renaissance context, one could view the dense cityscape and castle not just as representation, but also as indicators of rising merchant power, architectural ambition and trade routes as forms of material aspiration. The very act of engraving--its laboriousness--underscores a rising value placed on precision and detail in this era of expanding print culture. Editor: I see layers of symbolism here, perhaps unintentional but resonant nonetheless. The looming castle could represent power and protection, but the village being dwarfed by the clouds hints at impermanence, maybe even a looming sense of divine judgment on worldly pursuits. Consider how the artist renders the heavens versus the grounded dwellings! Curator: Interesting point. Though, to return to the more immediate materials and processes at play, we should consider that the engraving technique itself—etching lines into a metal plate, then using ink and pressure to transfer that image onto paper—was fairly new and transformative at the time, facilitating distribution on a much wider scale than ever before. So the choice of this printing method must influence the cultural perception of the work. Editor: It's tempting to get lost in analyzing the individual elements but I'm stuck on the people populating this landscape – notice that a lot of action happens around what seems to be a May Pole. Fertility and festivity versus an impending apocalyptic cloud, again I cannot deny a symbolic representation, perhaps of conflict, permeating the quotidian lives in the 16th century. Curator: It is true that the detail given to daily activities also tells us much about society at the time this work was produced and circulated. These types of scenes celebrated a moment in its material conditions but could also offer models of moral behaviour. Editor: Perhaps we're both correct; by looking at the materials as cultural signifiers, we allow a more inclusive interpretation of an engraving – rather than as just an art piece to admire and consider on aesthetic grounds, which deepens our appreciation for its role. Curator: Indeed, analysing the process and intention in tandem makes a comprehensive understanding for an artwork to thrive.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.