photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 17.5 x 15.7 cm (6 7/8 x 6 3/16 in.) sheet: 25.2 x 20.2 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

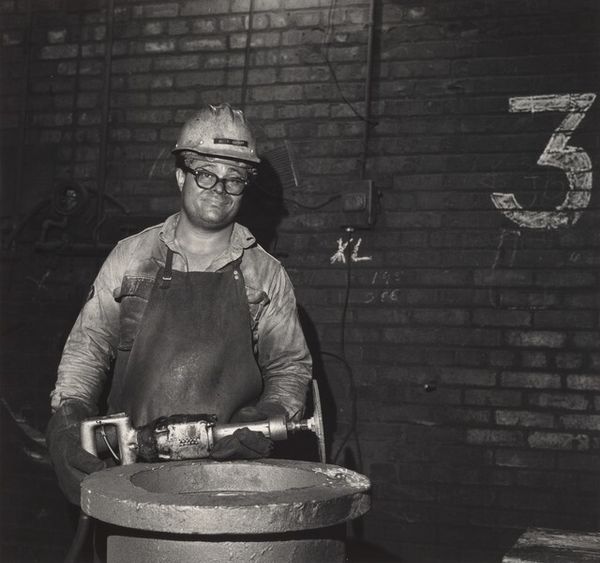

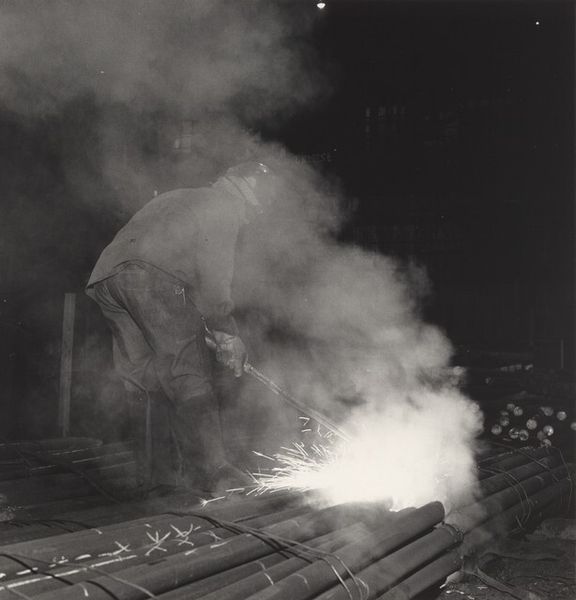

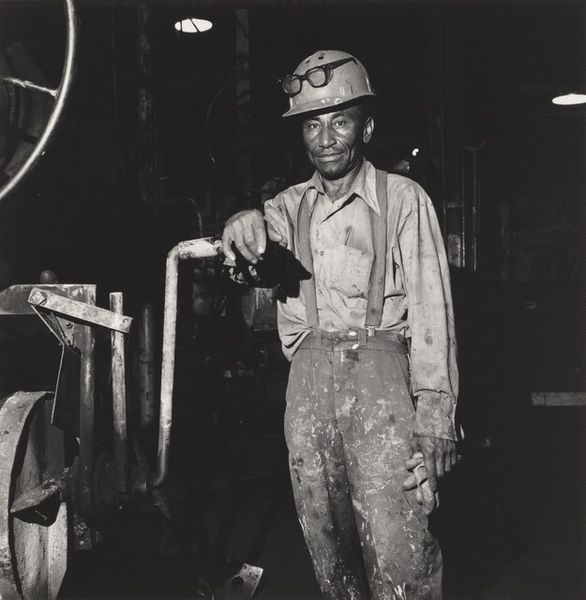

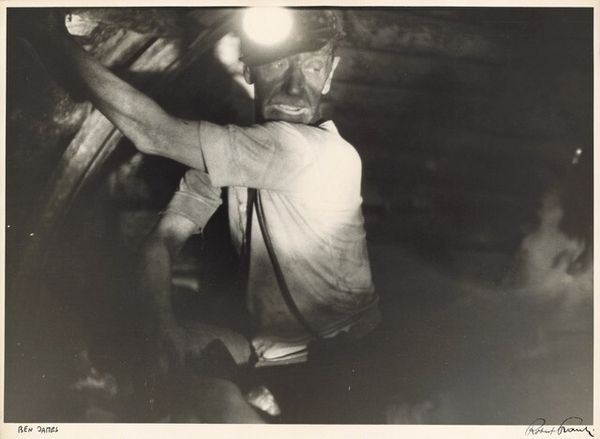

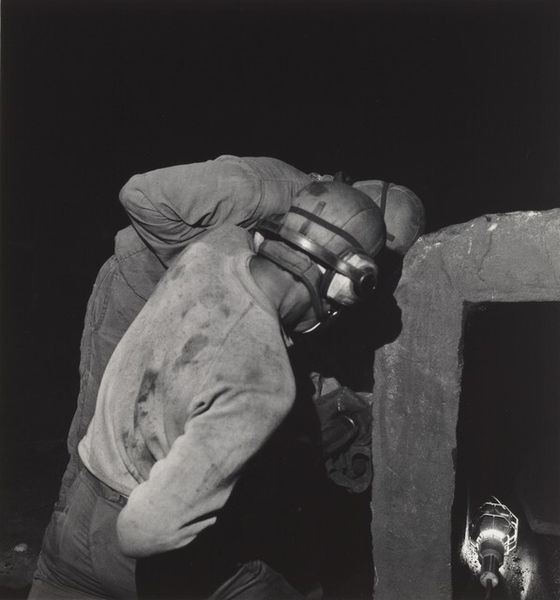

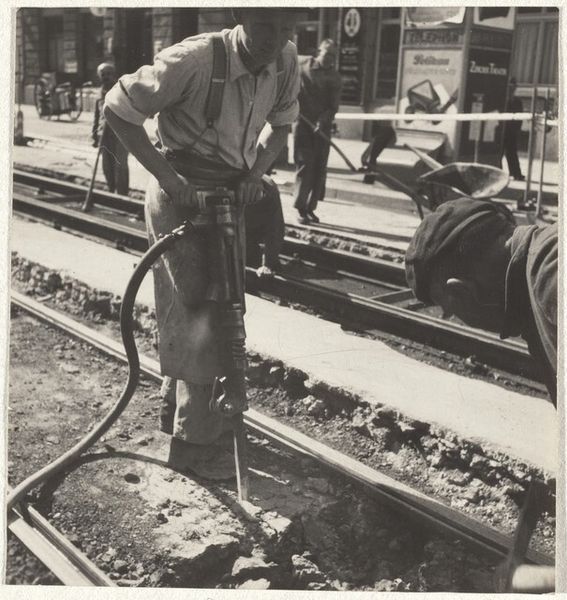

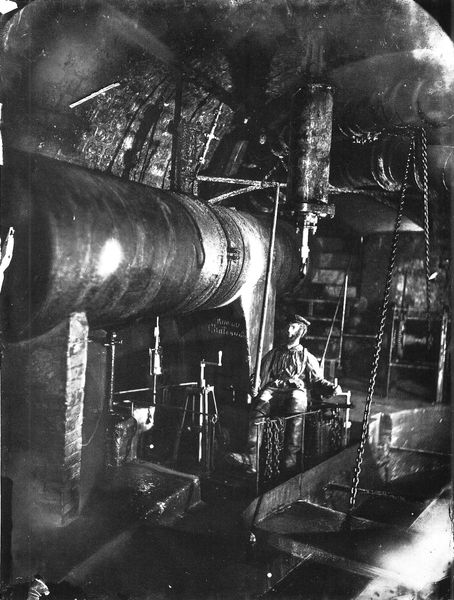

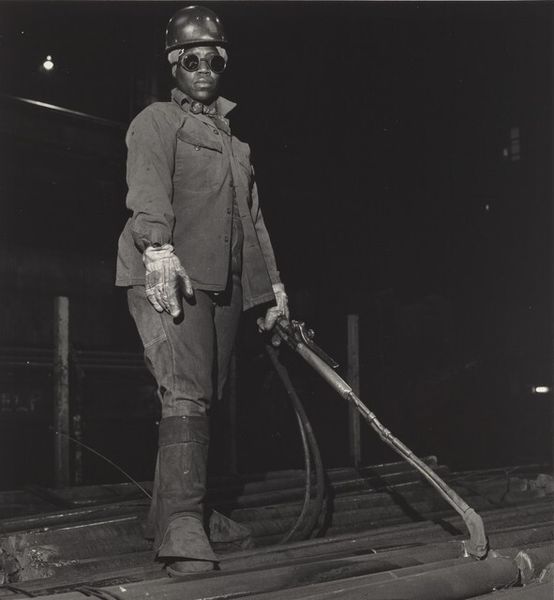

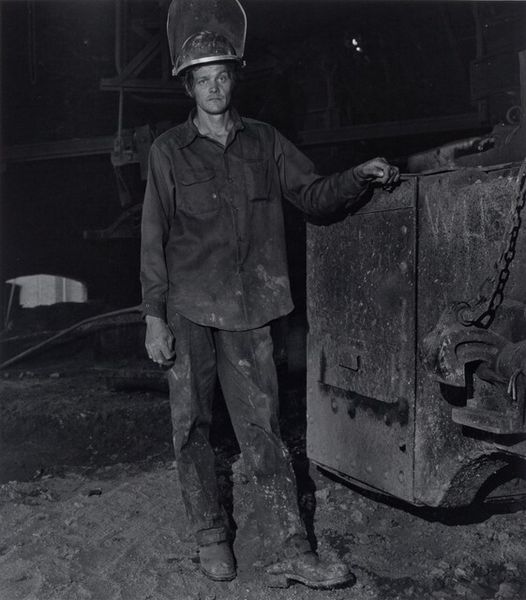

Curator: Milton Rogovin’s photograph, "Retiree, Atlas Steel Casting" from his "Working People" series, taken in 1978, is a powerful gelatin-silver print. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the dynamic contrast. The sharp, bright sparks of the welding arc explode against the gritty, muted tones of the industrial setting. There’s a real tension created between light and shadow, almost like a dance. Curator: The formal composition reinforces that tension, doesn’t it? Rogovin utilizes a relatively shallow depth of field, focusing attention on the immediate action of welding, while the periphery, though present, feels secondary. Note also how the strong diagonal lines, from the sparks and structural elements, contribute to this energetic, yet grounded effect. Editor: Absolutely. And from a historical perspective, this image is deeply resonant. Rogovin's project documenting working people is more than just an aesthetic study; it's a testament to the lives, struggles, and dignity of laborers during a period of deindustrialization. Atlas Steel Casting becomes emblematic of that era. Curator: Precisely. The socio-political forces shaping the working class are implicitly present. Rogovin employs a direct, unvarnished realism that transcends simple documentation. Consider how the anonymity created by the welder's mask invites a consideration of labor itself rather than the individual worker. Editor: That anonymity serves a critical function, highlighting the worker's role within a system. It subtly calls attention to questions of labor conditions, worker safety, and economic disparity. What are we saying, as a society, with how and under what conditions these workers are tasked to spend their days? Curator: True, but don't disregard the photograph's formal appeal; consider the stark, nearly geometric quality of shapes and forms. This is hardly a mere document. It transforms industrial labor into a tableau that carries its own powerful visual weight. Editor: I agree completely. What Rogovin manages to do here is render what might seem mundane as momentous, turning industry not just into work, but the raw stuff from which history itself is forged. Curator: Seeing this piece makes me think about how even seemingly "objective" images have compositional underpinnings, affecting how a viewer experiences them. Editor: And it shows us how portraits of labor serve not just as documentation, but powerful instruments for societal contemplation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.