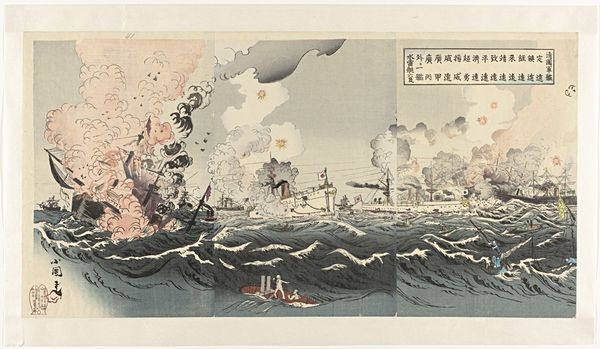

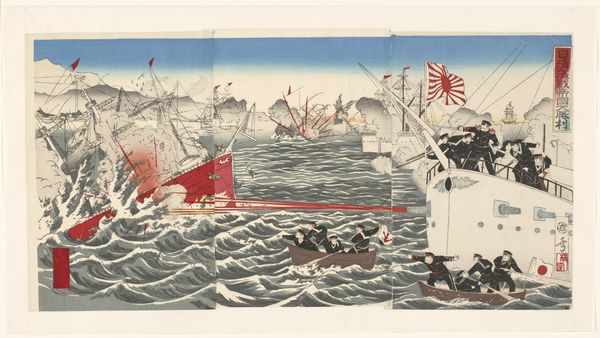

De overwinning van de Japanse marine na een hevige zeeslag nabij Dagushan 1894

0:00

0:00

utagawakokunimasa

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 369 mm, width 704 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Utagawa Kokunimasa's woodblock print from 1894, titled "The victory of the Japanese navy after a fierce naval battle near Dagushan," part of the Rijksmuseum collection. What is your first impression of this scene? Editor: It feels… overwhelming. A dynamic and terrifying clash. The choppy sea and the smoke billowing into the sky really evoke the chaos of naval warfare. I also can't ignore the way the image glorifies what seems like an act of violence. Curator: Woodblock prints, particularly ukiyo-e like this, were indeed often used to depict and, yes, celebrate current events. It's a fascinating lens into Japanese self-perception during the First Sino-Japanese War. Notice how the Japanese ships are prominently displayed in the foreground, symbols of national strength. Editor: Absolutely, there's a clear sense of national pride. This artwork definitely plays into the political context of that war. We are faced with an assertion of power—not just military might, but cultural as well. The text crammed on the print gives a documentary quality that works to amplify the scene in conjunction with nationalistic feeling. How do the cultural underpinnings come into play for you? Curator: Precisely. The woodblock technique itself, with its stylized depiction of waves and smoke, recalls earlier traditions while being put to the service of modern militarism. I find the almost mythical quality of the smoke plume to be especially compelling. It’s rendered in a way that suggests something beyond a mere explosion; it seems to be the emanation of a collective, even divinely sanctioned power. Editor: Yes, the smoke becomes this monstrous thing—and perhaps, allegorically, the dark shadow cast by colonialism itself. Considering Kokunimasa was a Meiji-era artist, do you think he intended for there to be some kind of a critique of imperial ambition within his celebration of war, or might that reading be an anachronism? Curator: It's tempting to retroject contemporary anti-imperialist views, but that might be overreaching. More likely, Kokunimasa was working within a dominant framework, celebrating national prowess and solidifying the image of a modern, powerful Japan on the world stage. Editor: That's probably correct. What really hits home for me is seeing art used so directly to serve political ideology—a chilling reminder of how imagery shapes and reflects power. Curator: It underscores the enduring power of visual symbols to mold and reinforce societal narratives. By exploring these historical artworks we confront uncomfortable truths about the complex relationship between aesthetics and ideology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.