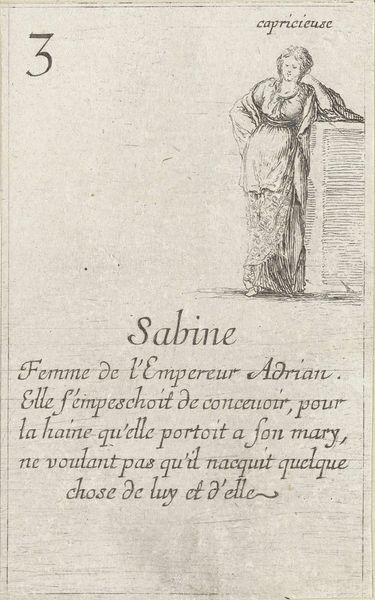

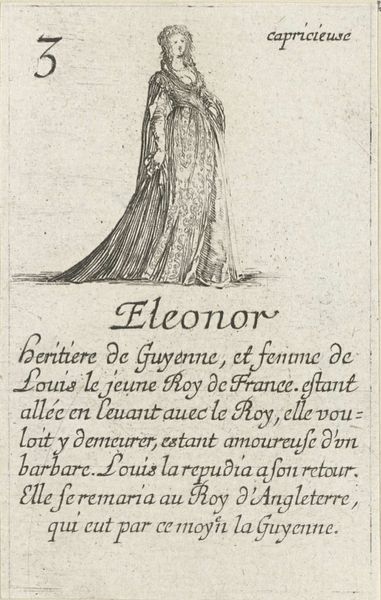

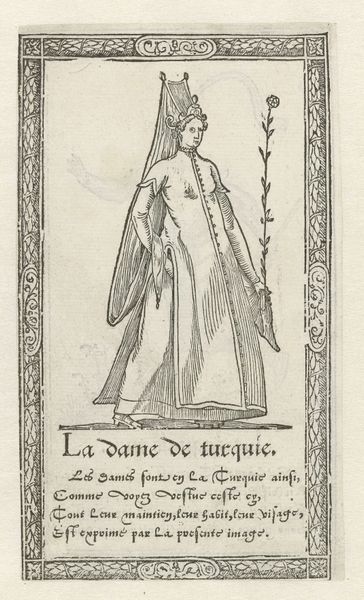

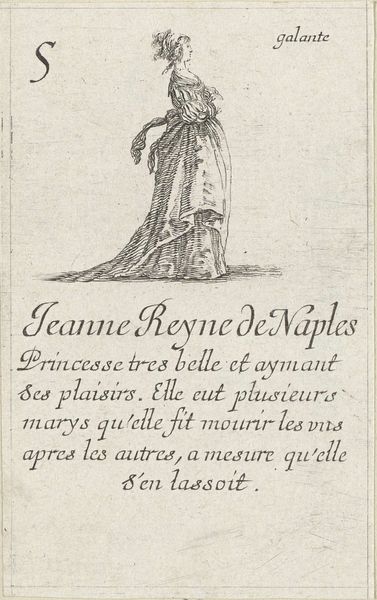

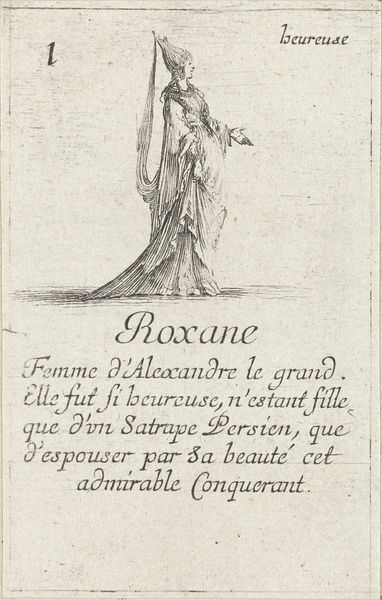

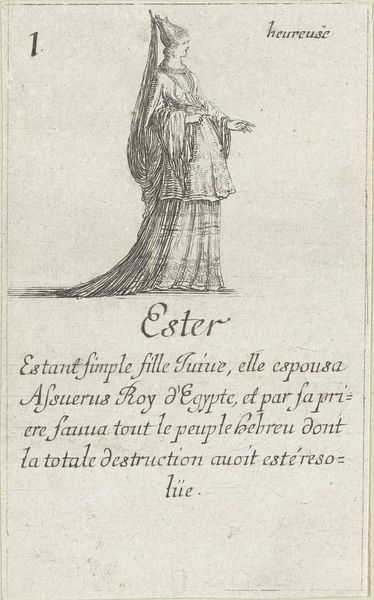

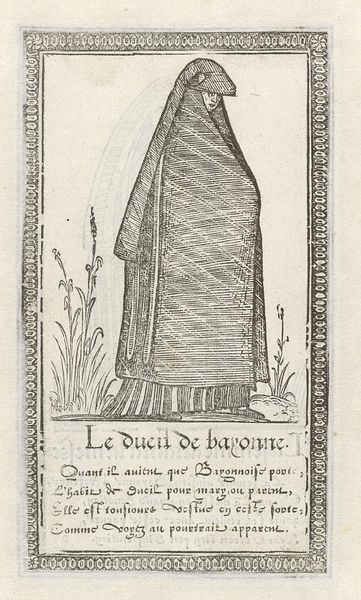

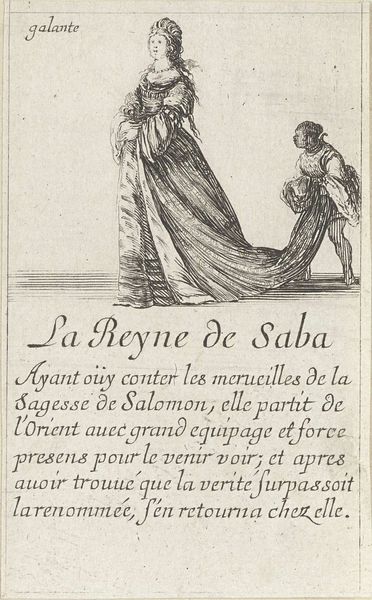

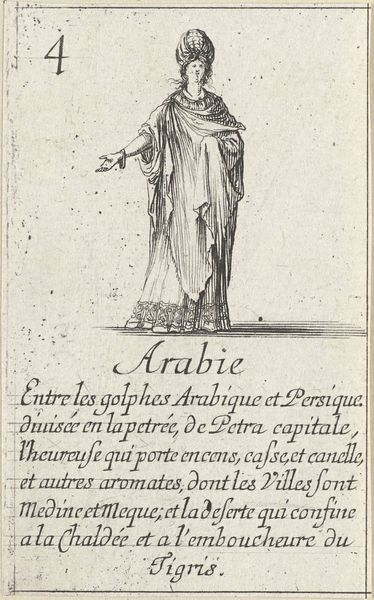

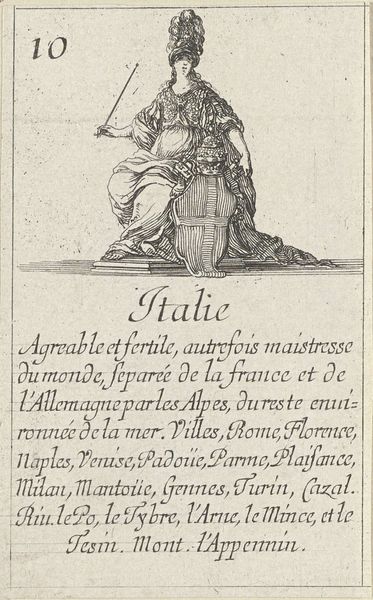

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 55 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Stefano della Bella created this engraving, titled "Julia Caesaris maior," sometime between 1620 and 1664. The print, done with a precise line technique, is currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There’s something melancholic about this Julia. Even in the fine details of her gown and feather, she seems burdened, a bit… defeated? The lines are delicate, but don’t quite convey opulence or celebration. Curator: You pick up on something essential. This image doesn't simply portray a noblewoman; it’s laden with political commentary. The inscription refers to Julia, daughter of Emperor Augustus and wife of Tiberius, who was exiled for "immodesty," a label often wielded against powerful women. Editor: Ah, so the “immodesty” here acts as a socially-accepted pretext for sidelining a woman from the center of power, then. What do you see this piece communicating about power? It's striking how much narrative context the artist manages to embed within such a minimalist style. Curator: Exactly! The artist uses the visual vocabulary of Baroque portraiture—the flowing gown, the elegant pose—but subverts it. By visually aligning Julia with societal expectations while simultaneously labeling her as "immodest," the artist critiques the hypocrisy of the Roman court. We must remember the pervasive narrative control held by the emperors and their biographers. This engraving serves as counter-narrative of the official version. Editor: It is interesting that the description is more concerned with Julia’s relationship to the Emperors as daughter and wife instead of focusing on her own personality. This tells us much about the place of women in society during that period, wouldn't you agree? Curator: I couldn’t agree more! It’s imperative that we examine depictions of women through this nuanced intersectional lens. Looking at the materials further confirms this analysis. The accessibility of printmaking at the time suggests this could be used as political discourse available to broad audience. Editor: Reflecting on the piece now, I still feel that sense of melancholy but understand the historical roots and commentary on powerful women. I see so much more agency here than I originally anticipated! Curator: And hopefully that perspective resonates beyond this gallery as well, provoking continuous discussion around art’s powerful role in mirroring and influencing perceptions about identity and gender dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.