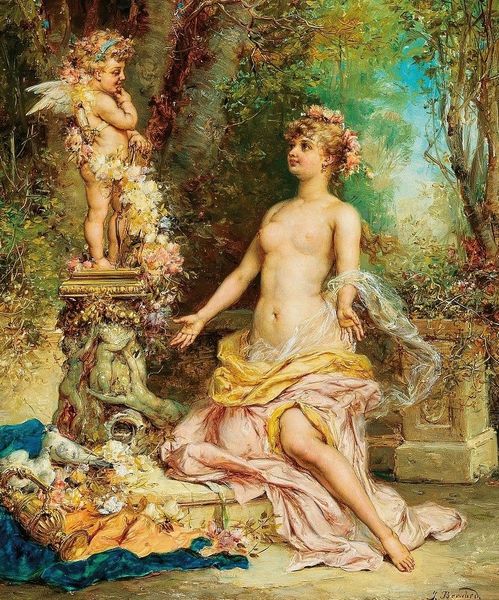

painting, oil-paint

#

allegory

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

roman-mythology

#

cupid

#

mythology

#

rococo

Dimensions: 164.5 x 84.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: This scene unfolds with an almost theatrical lightness. What’s your initial response to it? Editor: Ethereal, undeniably. It feels like a fleeting dream, almost excessively sweet. There's a sensual softness to the forms and a hazy quality to the light that is particularly striking. Curator: Agreed. We're looking at François Boucher's 1754 painting, “Amor a prisoner,” executed in oil on canvas. Immediately we're immersed in a classical Arcadian landscape where mythology intertwines with themes of captivity and freedom. It embodies the essence of the Rococo period. Editor: "Amor a prisoner..." So Cupid, god of love, finds himself bound? Is this the symbolism, or something more subtle? The winged cherubs do strike an oddly triumphant note hovering over those reclining figures. Curator: Well, Cupid's capture signifies love subdued, perhaps a warning against its untamed nature. It's important to remember the social function of Rococo art. These weren't radical, transgressive works but objects intended to reinforce social mores and political order for wealthy elites, all through allegorical visual display. The rosy flesh tones, the delicate draperies... They project power in an ideal, aesthetically pleasing guise. Editor: The arrangement certainly emphasizes pleasure. Though I wonder, given our modern sensitivities, how audiences respond to representations of idealized female bodies presented so openly, ostensibly for a male gaze, under the pretense of high-minded allegory. Is there tension between the intended moral message, love being restrained and social dynamics implied by the visual power relations between subject and beholder? Curator: Precisely, it presents us with complex questions regarding historical context and enduring cultural perceptions. Boucher’s masterful technique in capturing light and texture makes this canvas unforgettable. The figures are embedded in their artificial environment with remarkable skill, that communicates a sense of timeless beauty, though maybe tinged with artifice. Editor: Absolutely. It is important for art historians, but particularly, as an iconographer, to ask those crucial, uncomfortable questions and continuously interrogate cultural legacy through an analytical frame, if art is to act as a mirror, reflecting who we are. Curator: That's a fair call and something that is valuable for every single art historian to keep in mind. Hopefully, as visitors leave, they'll continue considering the questions we've raised. Editor: Indeed, thinking is its own form of freedom, maybe the truest kind.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.