print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

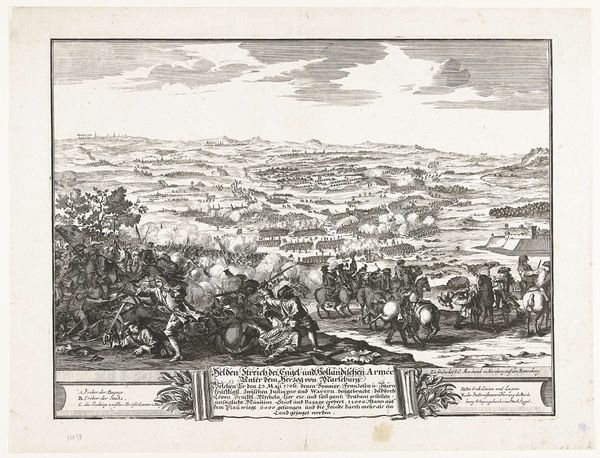

Editor: This print, "Gevecht bij Toledo," by Jacobus Harrewijn, probably created between 1682 and 1730, uses engraving to depict a chaotic battle scene with a city in the background. I’m struck by how the labor-intensive process contrasts with the instantaneous violence of the battle. What's your take on this piece? Curator: What I find fascinating here is precisely the relationship between the meticulous, almost mechanical process of engraving – the deliberate cuts, the calculated application of ink – and the representation of a scene of brutal conflict. The "Gevecht bij Toledo" isn't just depicting war; it’s *produced* through labor, like any other commodity. What statement do you think Harrewijn makes through the chosen printing medium? Editor: I see what you mean! It's as if he's using the medium to comment on the social context of warfare itself - how it is almost methodical and the creation of a power imbalance within society, similar to an industry. A sort of production of suffering. Curator: Exactly! Consider how the print would have been disseminated. It becomes a consumable object, a piece of war sold and distributed like any other commodity of its time. We tend to isolate “art” but this makes me wonder, where does craft end and art begin, or vice-versa? How can we tell the difference? The traditional division starts to crumble, doesn't it? Editor: Yes, that's a really interesting point. By examining the process and materiality, you realize that even representations of conflict can become part of a larger economic and social machine. Thanks, I will reflect on it more! Curator: It also pushed me to see traditional art categories differently by showing that art itself can perpetuate existing hierarchies. Something that might have been overlooked.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.