engraving

#

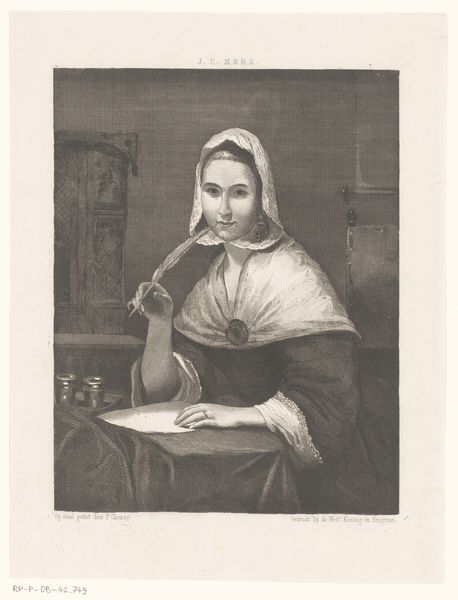

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

narrative-art

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 348 mm, width 268 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I am immediately struck by the overall serene melancholy radiating from this image. It seems the cold hues amplify that feeling. Editor: Indeed. This is "Nivôse (21 December – 20 January)," an engraving dating back to between 1792 and 1794. The artist is unknown, but we see the neoclassical style beautifully rendered here. Nivôse refers to a month in the French Republican Calendar, and as the title suggests, covers the winter solstice. Curator: I'm particularly drawn to the figure of the woman. Her downcast gaze, the way the fabric drapes—there’s a sense of quiet contemplation. It recalls, to me, many traditional artistic renderings of the Virgin Mary spinning or weaving. Do you see echoes of that visual language at play here, that iconography? Editor: Absolutely. The idealized features and the classical drapery consciously evoke that visual language of virtue and piety, yet she's not in a religious setting, which tells us how the Revolution adapted symbolic imagery for secular use. Notice also the sparse winter landscape glimpsed behind her, suggesting hardship but also endurance. It aligns perfectly with the virtues Republicanism wanted to instill: stoicism, resilience. Curator: So it's almost a symbolic alignment, then—her act of spinning with the larger context of the community providing for itself, finding sustenance and comfort during the hardest part of the year? The very essence of cultural survival is rendered visible here. Editor: Precisely. Spinning was often connected to female labor, to community sustenance and, because this was part of a series, a subtle connection was being made for the Republican calendar being necessary and ‘natural’ to society. The season isn’t being depicted as naturally hard, but being tamed by the feminine. Curator: How powerful, then, to subtly connect social stability to these domestic images! There’s so much communicated through a seemingly simple pose, and her engagement in domestic labor and winter landscape provides a foundation for collective meaning. Editor: Definitely, images like these had very concrete public roles to convey, during the Revolutionary period, what a modern virtuous citizen should be. Curator: A fascinating insight! Seeing how familiar themes become imbued with revolutionary zeal really does enhance our understanding. Editor: Indeed. It compels us to remember how closely interwoven art, power, and society have always been.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.